Yehudi Menuhin is indisputably among the top two or three violinists of the 20th century. The new boxed set, The Menuhin Century, makes a strong case for ranking him number one.

The others who belong in that tier are, in chronological order, Mischa Elman and Jascha Heifetz. At the beginning of the century Elman was a celebrated prodigy and his recordings were so popular that he was awarded a star in the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Heifetz was an awesome figure who had total technical mastery of his instrument.

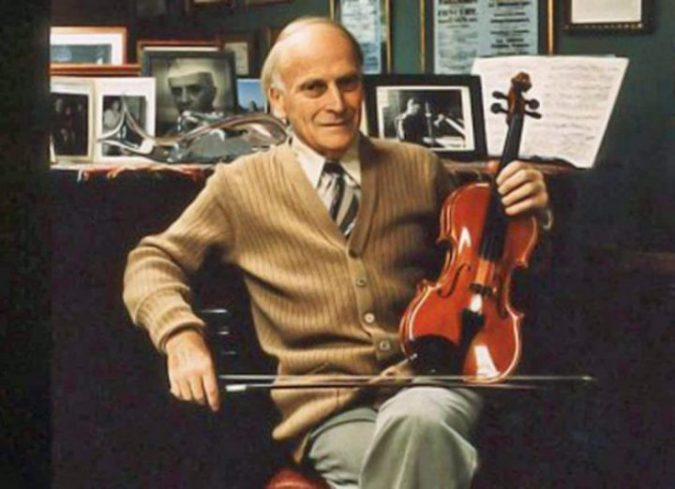

Menuhin, born April 22, 1916, had broader interests beyond playing the fiddle. He became a humanitarian and a philosopher, and now this album of recordings reminds us of his stature as a musician.

Bruno Monsaingeon, a Parisian concert violinist in his 70s, wrote a book which is included in the package and spoke with me about his friend. Menuhin practically put his career on hold in the 1940s, playing hundreds of concerts for Allied troops in hospitals and near the front lines. He played for displaced people at concentration camps, and Monsaingeon says Menuhin’s heart was broken by what he saw. “The contact with human suffering made him a different man. The Schubert Ave Maria he would always play, he said to me, as a kind of prayer for those who might not return.” Pain and anguish can be heard in many of these recordings, along with a unique sweetness.

Menuhin was born in America but became a world traveler, a “citizen of the world,” and eventually resided in England. Menuhin described his own playing as a distillation of different influences, “an overlay of French, German, Italian, English elements on a Russian-Jewish foundation….classical enough for the German, expressive enough for the Russian, polished enough for the American, elegant enough for the French, true enough for the British.”

He also described himself as a cosmopolitan who carried pollen from flower to flower to “inseminate, disseminate, weave webs and build frail bridges; it has remained my mission.”

Bruno Walter conducted Menuhin’s first concert, and recalled that “he was a child, and yet he was a man and a great artist.” By the age of 13 had performed in the capital cities of Europe. He matured from being a prodigy into an elder statesman.

His changes were fascinating. When he was a 16-year-old collaborating with Edward Elgar he played with sophisticated innocence, with reserve and austerity. He described Elgar’s music as “English to the point of being almost unexportable” expressing “flexibility within restraint….a grandfatherly country gentleman who should properly have had a couple of hounds gamboling at [his] heels.”

With the composer and conductor Georges Enescu he played with gypsy-like abandon. Menuhin recorded Bach’s sonatas and fugues three times, repeatedly changing them by what he described as “complicated wiggling and jiggling” so that “resolutions of dissonances could be heard.”

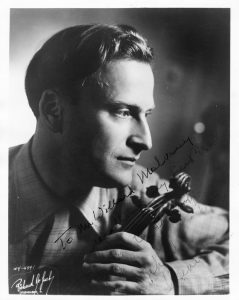

Below, Mehuhin in the 1930s:

Late in his career, Menuhin made jazz recordings with Stéphane Grappelli and albums of Eastern music with sitarist Ravi Shankar. He was quite a multifaceted man, and this album is a well-deserved tribute. The beautiful package from Warner Classics includes Monsaingeon‘s 250-page book, loads of photographs, 80 CDs and 11 DVDs. The recordings date from 1928, when Menuhin was twelve, to 1999 when he was 83, just six weeks before his death.

It has taken me a long time to hear and see everything in this collection, partly because I kept re-playing some of the fascinating selections. Separate boxes within the big enclosure are devoted to The Historic Recordings, Live Performances, Recitals, Unpublished Recordings, Menuhin on Film, and his collaborations with his pianist-sister Hephzibah.

Much of it is profound, other selections are playful. Highlights include a lush Swan Lake led by Efrem Kurtz with Menuhin’s idiosyncratic violin solos; a complete 1940 Carnegie Hall concert of Bach, Brahms and Paganini; sonatas of Aaron Copland and Roy Harris; and Brahms trios with Pablo Casals and Eugene Istomin. Also the unaccompanied sonata which Béla Bartók wrote for him which Menuhin described as “the most aggressive, even brutal music I play.” Miniature gems are presented by Tartini, Locatelli, Fauré and Kreisler, and we certainly appreciate his excursions with Grappelli and Shankhar.

If you are tempted to bypass the box devoted to Mehuhin’s Complete Recordings with Hephzibah, do not do so. Not only was she an accomplished pianist in her own right; this box includes their collaborations with distinguished colleagues such as cellist Pablo Casals and French horn player Alan Civil. I know of no other violinist who recorded so many fine chamber music partnerships. They were made between 1936 and 1978. One of my favorites is the Ralph Vaughn Williams Violin Sonata in A minor.

A bit of trivia: Mehuhin’s original family name was Mnuchin, the same as the banker and new Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin.

And now, please excuse me as I go back into the box to listen to more treasures.

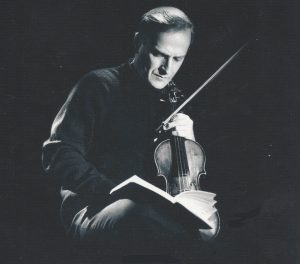

Below, Menuhin and Elgar in a 1932 concert: