Tancredi by Rossini. Opera Philadelphia, February 2017.

A rare Rossini opera has been revived as a vehicle for star mezzo Stephanie Blythe. It turns out to have many additional merits.

Who would suspect that an opera written in 1813 would relate to today’s international events? Yet Gioachino Rossini’s Tancredi involves warfare between Muslim armies from the Middle East and the western Christian powers, and the plot is based on fear of terrorism. The people of Syracuse fear attacks by the Moorish people, Muslims.

In this opera the western nations feel danger all around; but the bad times are over and Syracuse is going to be great again.

The libretto is based on a play by Voltaire, and it specifies the years shortly after the Crusades, when East-West hostility was rampant and Saracen was the name applied to Muslim Arabs and Turks. The designer and director here updated the setting to the 20th century, at the end of World War I, although they could have achieved more immediacy if they emulated our 21st.

The set resembles the palace at Versailles, which was the locale for the peace conference after the Great War when ethnic and nationalistic hostilities were being put to rest, even though that does not comport with the theme of this opera. Many characters wore elaborate military uniforms similar to what some German and Austrian generals wore during that war, but were actually more reminiscent of the Napoleonic era.

(Director Emilio Sagi informed me that “the end of the First World War showed a chivalry world” that was implicit in the plot and was, to him, “more interesting visually.”)

Since Rossini composed the opera one year after Napoleon’s momentous defeat, I wish the director had portrayed 1812 which also was the time of its composition. Accepting this director’s choice, the staging does have some striking scenes. Yet there are other, better reasons to hail this production.

By reviving this piece, Opera Philadelphia has provided a major revelation. Rossini is known for his comic operas like The Barber of Seville, The Italian Girl in Algiers and Cenerentola, and few people recall that he rose to fame at age 21 with this serious drama. It’s a dark story of a soldier from Sicily who went into exile in the land of the Saracens, then returned — supposedly — to lead a battle against his people. That’s what the Sicilian nobles believed, based on an intercepted letter to Tancredi from his sweetheart Amenaide, who was the daughter of the Senate leader Argiro. The letter was mistaken as an invitation to the Saracen commander which appalled all the Sicilians.

Amenaide deliberately omitted Tancredi’s name from her letter because it was to be delivered to him in exile and she wanted to protect his whereabouts. Someone should have understood her story; the level of distrust by everyone in the opera is massive.

Amenaide’s father forces her into a loveless marriage with his political ally Orbazzano. When Tancredi learns of this he’s angry that Amenaide has been unfaithful. Meanwhile, everyone in Sicily believes that Amenaide’s a traitor because she corresponded with someone on the enemy side. Her father disowns Amenaide and signs an order for her execution. The lady is alone, despised by everyone.

The conflicted Argiro agrees to allow a champion to duel Amenaide’s husband with her life in the balance. The disguised Tancredi volunteers for the task, wins the fight, and goes on to lead the Sicilian army to victory over the Saracens. That could have been the happy end to this opera.

Rossini wrote a festive ending with a catchy chorus for the 1813 premiere. For a later production he removed the happy finale and composed a tragic ending in which Tancredi’s army wins the battle but he is fatally wounded. This sad final scene was not discovered until 1977, and it’s what Corrado Rovaris led in this production.

The unusual opera was selected as a star vehicle in which Blythe could play the trousers role of Tancredi. She made a powerful impression, justifying the choice — and making one yearn for productions in major houses, and for a recording. Her voice is like a majestic organ, swelling with rich tone and volume. She has a baritone-like timbre which helps the audience accept her as a male warrior. From her highest notes to her lowest, her voice is seamless, with no shifting between registers. Her projection is outstanding.

The musical merits of the production extended far beyond Blythe’s performance. Brenda Rae as Amenaide scored a star-making impression, with long lines and an affecting lyric quality even beyond her ability to sing cascades of coloratura roulades. As her father Argirio, the tenor Michele Angelini impressed with his refinement as he navigated a florid variety of emotions and melodies. His arias were the most dazzling of the evening. Another star has arrived.

The dependable baritone Daniel Mobbs was Orbazzano, while Allegra De Vita from the Academy of Vocal Arts contributed strongly as Amenaide’s best friend and Curtis Institute student Anastasiia Sidorova handled the smaller role of Tancredi’s attendant. Conductor Corrado Rovaris deserves immense credit for coaching these artists in this unfamiliar work and achieving an affecting melding of voices in the numerous duets that are the heart of the opera. The chorus was better than usually heard at a Philadelphia opera production; the male ensemble in particular was powerful.

The complicated (and sometimes baffling) story keeps Tancredi from being performed at major opera houses, but Rossini’s music is quite refined and lovely. His tragic ending is unusually stark. Most of the singing in that scene was accompanied only by Grant Loehnig on a solo fortepiano — and Rossini wrote nothing but quiet string tremolos as Tancredi died in his lover’s arms.

This finale was unusual for its time, and anticipated the quiet death scenes that Verdi later composed in La Forza del Destino and Aida. (We must observe that Verdi wrote melodies that were transcendently more beautiful.)

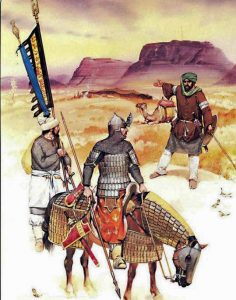

Below, painting of Saracen fighting Christians, courtesy of byzantium.com:

The sets by Daniel Bianco replicated Paris’s palace at Versailles. But the libretto says the action takes place in Sicily, where you won’t see anything like those massive rooms with high ceilings. Their towering presence, and a colossal monument in the final scene (which he based on a mausoleum in La Recoleta cemetery in Buenos Aires) dwarfed the players and reduced the intimacy of the opera. So did the processions of dinner guests and other wandering crowds in several scenes.

These distractions were minor flaws; Opera Philadelphia scored a major achievement in presenting such an accomplished performance of a rare work. The company is striking an excellent balance these days between standards, new compositions, and rarities by old masters, such as this.