The impresario Emil Gutmann didn’t do Gustav Mahler a favor when he invented the nickname “the Symphony of a Thousand.” It helped sell tickets in Munich in 1910 but the name raises unfair expectations among listeners.

To generate publicity, Gutmann devised the name and invited to the premiere of Mahler’s 8th the composers Richard Strauss, Camille Saint-Saëns and Anton Webern, the writers Thomas Mann and Arthur Schnitzler and the theater director Max Reinhardt. (Mahler wrote that he feared Gutmann would turn the event into “a catastrophic Barnum and Bailey show.”)

Despite its massive forces, the real soul of Mahler’s Symphony of a Thousand is in the intimate, quiet passages, as revealed by Yannick Nézet-Séguin in a concert staged on the 100th anniversary of the work’s American premiere. Opera stars Angela Meade, Stephanie Blythe, Lisette Oropesa, Anthony Dean Griffey and John Relyea added to the sense of occasion.

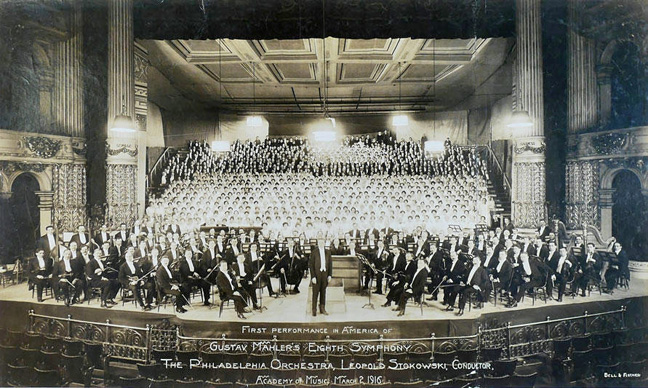

Leopold Stokowski, then age 28, attended rehearsals for the piece’s debut in Munich, obtained the rights to give the symphony’s American premiere, and mounted it with massive forces at Philadelphia’s Academy of Music in March of 1916. Men’s, women’s and children’s choruses of 950 plus vocal soloists and an enlarged orchestra of 110 brought the total to 1068 persons. The stage of the Academy was greatly extended, and 24 risers seated the singers.

Three performances were scheduled for one weekend, but six additional concerts were added, plus one more in New York. Ticket were scalped for as high as $100, which was more than what people paid for Philadelphia Athletics and Philadelphia Phillies World Series tickets in the prior two years. (Yes, both Philadelphia teams played in the World Series in consecutive seasons.) The acclaim made Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra one of the best-known attractions in the music world and vaulted the city to cultural preeminence.

Yet, upon reflection, the true achievement of the piece is in its intimate sections.

To be sure, massive instrumental forces are specified in the score and were used in Yannick’s concerts: Two piccolos, four flutes, four oboes, a cor anglais, three B-flat clarinets, two E-flat clarinets, a B-flat bass clarinet, four bassoons, contrabassoon, eight horns plus assistant (so 9 players), four trumpets, four trombones, tuba, tympani, cymbals, bass drum, tamtam, triangle, low-pitched bells, organ, harmonium, piano, four harps, celeste, mandolin, plus four more trumpets and three trombones offstage. (Nézet-Séguin actually used a few more orchestral players than Stokowski did in 1916.)

Yet they play in unison during less than half of the score. The opening Latin hymn, Veni creator spiritus (“Come, creative spirit” or “Come, spiritual creator”) is loud and lasts 25 minutes. Most of the 55 minute second half is quiet. The long orchestral prelude to Part II is very soft, and is followed by piano passages for chorus accompanied by a single violin. Immediately before the final chorus is a low-volume section for just piccolo, flute, harmonium, celesta, piano, harps and a string quartet.

This is analogous to Verdi’s Aida, which is commonly associated with onstage trumpets and camels but whose essence really is a love story with intimate duets. Mahler created a meditation about finding eternal hope through love, especially through the example of Goethe’s Gretchen, who ascended to heaven even though she had a baby out of wedlock and killed that baby, saying: “Whoever strives, in his endeavor, if he has love within, the sacred crowd will meet him with welcome and with love.” The text for Part II is the final scene of Goethe’s Faust, in German, ending with (in the excellent translation by A. S. Kline) “The indescribable, here, is done. Woman, eternal, beckons us on.”

It’s worth noting that neither Goethe nor Mahler were conventionally religious. Both were pantheists who revered nature. The words used are “Eternal” and “Nature” instead of “God,” and the name of Christ is omitted. The Veni creator theme seems to quote Maos Tzur, a Jewish hymn sung at Hanukkah.

Familiar aspects of Mahler’s compositions, such as birdsongs, military marches and Austrian dances, are almost entirely absent. Mahler thought of this work as separate from all his other creations, a synthesis of symphony, cantata and oratorio, with spiritual and psychological importance.

Eight months after conducting the premiere, Mahler died at the age of 50.

Nézet-Séguin led a performance that stressed continuity of soft, buoyant, floating sounds and delicate colors, punctuated with incisive entrances by varied sections of the orchestra. He used much smaller vocal forces than in 1916. The massed choirs totaled “only” about 300 but produced impressive volume when needed, and contemplative softness as well. Soloists included some of the biggest names in opera, such as Meade, Blythe, Griffey and Relyea and Lisette Oropesa added her ethereal soprano voice from the rear of Tier 3 in the closing minutes.

The entirety of the enterprise made a staggering impression, yet it’s the quiet parts, and Mahler’s expectations of eternity that resonate most.

Nothing can match the experience of hearing this in person, but performances are being recorded live with plans for a commercial CD release.

Below: Stokowski leads the Philadelphia Orchestra’s performance in 1916

Please share your thoughts and your opinions with us. Address to editor@theculturalcritic.com

Read other reviews on The Cultural Critic