Tristan und Isolde by Richard Wagner. Mariusz Trelinski director, Simon Rattle conductor. New production opening the season at the Metropolitan Opera, 2016. Telecast to movie theaters by Fathom Events.

Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde is a classic because of the co-equal melding of its story of a doomed extramarital romance, with breathtaking music that expresses unfulfillable desire. Wagner’s music suspends its harmonies and obsessively yearns for a resolution that doesn’t come until the final chord, when both of the lovers are dead.

The new production that the Metropolitan Opera chose to open its season, and to start its series of HD movie presentations, fails because it flagrantly separates those twin achievements.

Director Mariusz Trelinski conceived a modern and militaristic alternative story with off-putting distractions. I admired Trelinski’s production of Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle at the Met last year, but he’s way off base with this interpretation.

He took the incidental fact that Isolde travels by ship on her way to marry King Marke and made the ship the focus of the entire five-hour enterprise. The atmospheric ten-minute prelude was accompanied by an annoying, repetitious flashing of a rotating sonar screen, and the entire first act concentrated on the inner workings of a modern naval vessel.

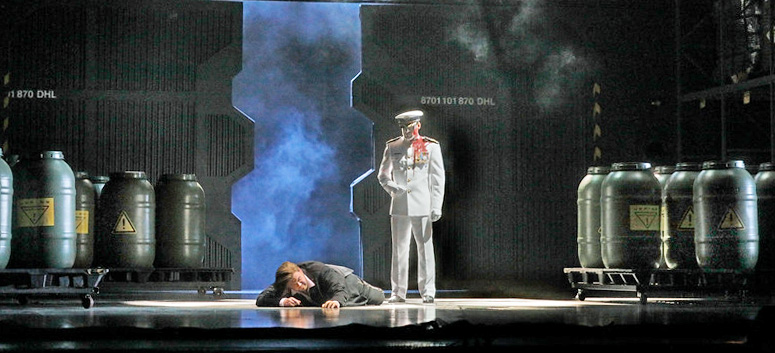

Worse yet was Act II where the music evokes hunting horns and the lyrics speak of the king, his huntsmen and their hounds moving off into the woods, yet Trelinski had the action take place on the ship. When Tristan and his beloved are supposed to have a night of rapture alone in a garden, this production has them go down flights of steps into a dreary storeroom filled with kegs.

Act III was set in a sterile hospital room, where Isolde reaches into a drawer, pulls out a knife and slashes her arm. Others are in the room but no one makes a move to stem the bleeding and save her life.

This contradicts Wagner’s depiction of a woman who ethereally wills herself to death where she can eternally be together with her lover. Wagner’s music has no hint of violence in this scene, but rather a yearning, quiet, upward journey.

Such misdirection was even more noticeable in the HD screening in movie theaters, expertly directed for the wide cinema screens by Gary Halvorson and telecast worldwide by Fathom Events. Enlarged closeups revealed the lack of passion in face and body language.

Nina Stemme is the outstanding Isolde of this generation, though she can’t match the vocal transcendence of Kisten Flagstad or Birgit Nilsson in their times. She phrased well and gave meaning to her words. Stuart Skelton was singing his first Tristan, and did so with a mellow voice rather than a brilliant, clarion one. Ekaterina Gubanova’s mezzo was warm and rich in the role of Brangäne and René Pape was a majestic King Marke clad as an admiral in white uniform.

Strangely for an opera about the physical attraction of lovers, there was no chemistry between Stemme and Skelton. During their long night alone together, from sunset til dawn, there was hardly any embracing and he remained fully clothed in his naval uniform. Keep in mind that half of the reason for this opera’s popularity is its evocation of torrid extra-marital sex.

It’s no coincidence that two conductors most prominently associated with Wagner’s music in the 20th century were Arturo Toscanini and Leopold Stokowski, both of whom were known for their own extra-marital affairs. Philadelphia Orchestra subscribers from the 1930s say that when Stokowski led the Tristan und Isolde love music—which was very often—they would suspect that he had a new mistress and would look to his box to see what woman was seated there.

Even if we accept Trelinski’s concept of people trapped inside a ship, it’s an error to eliminate eroticism from this opera.

Stemme demonstrated how well she can act in last season’s Elektra, so we can’t fault her. And there’s no reason to question a middle-aged woman having an intense affair. Yet Stemme here appeared stolid and dispassionate.

Simon Rattle’s conducting was well-calibrated to put emphasis on the singers, without unusual mannerisms, and was superbly played by the Met orchestra.

This was the first Met opening night Tristan und Isolde since 1937. What a terrible missing of opportunity!

On the right, Stemme’s Liebestod:

Below, the death of Isolde, painted by Rogelio de Egusquiza: