Written on Skin, music by George Benjamin, libretto by Martin Crimp. Opera Philadelphia, February 2018.

The Opera Philadelphia production of this opera — its first original staging in the United States — is a triumph. It was a risky endeavor that paid off with superb music, tantalizing drama, and is an exciting crowd pleaser.

This success was by no means assured, because the music is labeled as atonal, a word that scares many opera-goers. The term is misleading; it does not literally mean that tones are lacking. All music consists of tones, of course, and even the most “atonal” writing uses the same tones — that is, notes — that we all know. What’s unique is that composer George Benjamin does avoid the traditional rules about what specific tones should follow other tones, with prescribed scales and chords and signature “keys.”

Atonal music was derided a century ago as ugly and dissonant, but Written on Skin sounds strange and beautiful. Benjamin’s score is mostly quiet and subtle. When brass instruments come forward they are muted, and no singer needs to scream to be heard.

The story is intimate, centering on a husband, wife and a young man who has a sexual affair with the wife. Thus you might consider Written on Skin to be a chamber opera, except for the fact that it requires a symphonic orchestra of 63 players. Benjamin, age 58, is a renowned English composer, pianist and a longtime teacher of composition at the Royal College of Music. A scholarly-looking man, he said in conversation after the performance that he is meticulous and demands precise coordination of text with instruments.

His score incorporates a bass viol, a medieval instrument that has six strings made of animal gut and is fretted, producing an earthier sound than a cello; and a glass harmonica, a set of rotating glass bowls that are played by the touch of dampened fingers. Also, mini tabla drums and a mandolin. These instruments fuse with the orchestra, going into the mix of sounds rather than calling attention to themselves, like an Impressionist painter adding a squeeze of color to his palette and blending it on the canvas. Its closest antecedent is Debussy’s Pelleas et Melisande which similarly is a delicate, intimate story told by human voices with a huge but transparent orchestra.

Benjamin and the librettist Martin Crimp started work on this composition in 2008 and they had no inkling of America’s political climate in 2018 and the Me Too movement for women’s rights. Yet Written on Skin is remarkably prescient in its view of patriarchy and misogyny. The creators set the opera in medieval times to give the story universality, framed with present-day scenes that include references to multi-lane expressways, an airport and computers.

A man called The Protector is an arrogant and wealthy landowner who brags that his estate is the biggest and most beautiful. He treats his young wife as his property — “My obedient wife’s body is as much my property as my dog” — and shows little affection for her, or for any woman. He hires a young man, called The Boy, to create an illuminated manuscript that will memorialize the Protector’s great accomplishments. Such illuminations were medieval works of narrative art, inscribed on animal skins, thus inspiring the opera’s title.

When Boy meets the trophy wife he treats her with more respect than her husband ever did, and she responds by entering into a passionate affair. She implores Boy to include their love affair in the manuscript and, after resisting for awhile, he insists on describing their affair with words. (She, as most medieval women, was raised to be illiterate.) The two of them engage in a struggle for control, mirroring the Protector’s controlling behavior.

When Protector learns of the affair he murders Boy; but that’s not enough. For sadistic revenge, he cooks Boy’s heart and serves it to his wife for dinner.

Benjamin revealed that Written on Skin’s original title was to be Black Mirror until a British TV series by that name debuted in 2011. That is a science fiction series, loosely based on The Twilight Zone but darker. It’s now running on Netflix.

Tom Rogers’s set and Will Kerley’s direction substitute iPads for manuscript pages, and add vivid colors to the original gray tones as the illuminations progress. Benjamin similarly uses his orchestra, he explained, “like a colored background, almost as an illuminator might.”

This cast is marvelous. Lauren Snouffer reveals a warm and glowing soprano voice as the wife, seeming to surprise herself with her new-found assertiveness and passion. The British baritone Mark Stone does the best work of his career as the husband, with soaring top notes. Countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo uses his head-voice falsetto to stunning effect and is dramatically compelling as the lover. Departing from the precedent of others in this role, he introduces some climactic notes that are chestier, almost spoken, as if a bit of Protector is coming through into the Boy.

Mezzo Krisztina Szabo and tenor Alasdair Kent nicely complete the cast as supporting characters and as angels, which are devices carried over from the thirteenth century Provençal legend Guillem de Cabestanh, La Coeur Mangë (William of Cabestan, the Eaten Heart) on which Crimp and Benjamin based their story. Cabestan is located in the Pyrénées mountains between Spain and France, 90 miles due north of Barcelona.

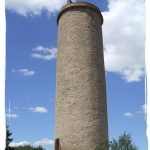

To the right, the actual tower that inspired the final scene.

Composer Benjamin and librettist Crimp chose to frame the legend with references to our time, where evils such as misogyny, domination, domestic abuse, violence and revenge still are rampant. In the Philadelphia production the first scene shows glowing oblongs which resemble skyscrapers, and an angel sings “Dismantle them. Force chrome and aluminum back into the earth. Make way for the wild primrose and slow torture of criminals. Fade out the living; snap back the dead to life.”

Corrado Rovaris is impressive in the subtlety of his conducting, which Benjamin says is essential. Possibly because he is Italian, Rovaris’s previous work with modern, non-Italian operas has not been adequately recognized, even though he has expertly led Philadelphia performances of such contemporary works as Ainadamar by Osvaldo Golijov, Powder Her Face by Thomas Adès, Phaedra by Hans Werner Henze, and Elizabeth Cree by Kevin Puts and Mark Campbell.

His conducting here reveals the beauties of Benjamin’s score as the lovers ascend to haunting high notes during their first meeting. Benjamin described it to me: “It’s a pivotal moment in the narrative, and one for which I tried to capture something special. The real core of the matter, I believe, is not the orchestration but the harmony, and that has been set up over the several minutes of music beforehand. But to be specific and more precise: the two voices (countertenor and soprano) settle on a major third (A/C-sharp) which is joined by very high, soft horns who eventually add the E above, creating an A major triad in the treble register.”

Such a major triad (three notes, evenly distanced from each other) is considered by musicians to be a consonant and comforting chord. This lovely passage follows the words of Agnès, “Can you invent a woman who’s real, who can’t sleep, who said that her heart split and shook at the sight of a Boy? When you have invented and painted that exact woman, come to me.”

To put it another way, in this drama about mistreatment and violence, here we have a grand affirmation of love. Who says that atonal music can not be romantic!

In this opera, only the woman is given a name, Agnès, and I believe that was intentional; the composer and librettist have subtly created a treatise on women demanding recognition.

Written on Skin was commissioned by the Aix-en-Provence Festival and premiered there, then at Covent Garden, and its Aix staging was presented in 2015 at the Koch Theater in New York’s Lincoln Center. That production was set more specifically in a rustic medieval farmhouse. This Philadelphia staging is more timeless, and effective. It’s an independent production, without co-sponsorship by any other company, and is one of this organization’s most significant accomplishments.