The Curtis Institute of Music and Opera Philadelphia are presenting the stage premiere of a radically altered version of A Quiet Place, the opera that Leonard Bernstein wrote towards the end of his life.

The Philadelphia performances are the first-ever staging of an altered version that is much more intimate, and daringly different from what was previously known. This is notable for extra-musical reasons as well, because it was Bernstein’s attempt to work out issues within his own family.

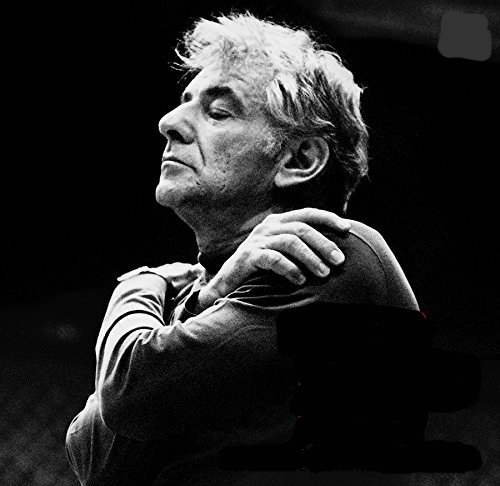

Acclaimed for his multiple talents as a conductor, pianist, educator and composer, Bernstein biggest frustration was that he had not written a serious opera. And people at the Leonard Bernstein Office believe that this reworking reveals Bernstein’s feelings.

At its premiere at the Houston Grand Opera in 1983, A Quiet Place was a 110-minute work in four scenes, using a very large orchestra that included synthesizer and electric guitar. The libretto was by the young director Stephen Wadsworth. It was on a double bill, preceded by a performance of Bernstein’s 1951 comic opera Trouble in Tahiti (for which he wrote the words and music.) The authors were dissatisfied and so they changed A Quiet Place into a three-act opera which premiered at the Vienna Staatsoper in 1986. Bernstein recorded that version for Deutsche Grammophon.

A substantial amount of A Quiet Place material was cut to accommodate the entirety of Trouble in Tahiti, which now was incorporated as a flashback in Act II. Another staging of that version was presented at New York City Opera in 2013. The new version is in three acts presented with very brief pauses between acts and lasting one hour and 40 minutes.

The main characters are the children of Sam and Dinah, named Dede and Junior, plus Junior’s lover François. Dede also is attracted to François, marries him, and they live together as a family — or is it a ménage à trois? Sam and Dinah are shown as bitter antagonists, fighting in the presence of their children, as Leonard’s parents had done. In the 1986 version, Sam reads Dinah’s old diaries and that evokes memory of thirty years earlier when the family led a “ideal” life in 1950s Suburbia. (The lyrics spoke of a little white house in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania.)

Garth Edwin Sunderland is a composer and producer of music and dance. He explains that the Leonard Bernstein Office came to believe that a chamber version of the opera, with a reduced orchestration, would allow for a more intimate experience of this deeply personal work. This version would not include Trouble in Tahiti, because its jazzy nature was so different from Bernstein’s later style, and it would restore some of the fine music that was cut from the Vienna version, including arias for Sam and François.

Kent Nagano conducted Sunderland’s chamber adaptation in November of 2013 in a concert performance with Ensemble Modern in Berlin. The Philadelphia performances in March 2018 are its stage premiere. Sunderland describes A Quiet Place as “at its heart, the story of a father and his children grappling with their history of bitterness and anger, and ultimately attempting, tentatively, to overcome it and reconcile.”

Most of the world now knows that Leonard had sexual relationships with both genders, and that Bernstein’s father Sam was dissatisfied with his son. Leonard’s opera includes similar situations. The names are barely changed. The father is called Sam and the mother is called Dinah, which is the name of Sam Bernstein’s mother. (Perhaps because Leonard’s mother’s name, Jennie, ends with a harsher vowel.)

Bernstein himself said of the score, “It sounds like no other work by me or by anybody else I know of…It has a special language and sound all its own.” Sunderland says, “I have gone back to the original impulse; revisiting the lean, modern concept behind the Houston version, and incorporating the improvements that Bernstein and Wadsworth made for Vienna, while restoring both the music and the characterization that were lost in the process of that revision.”

As mentioned earlier, this version is shorter. Trouble in Tahiti is no longer included in the middle of A Quiet Place. Sunderland also cut dialogues for the secondary characters at the top of Act I (during the funeral for the mother) allowing for an earlier entrance of the principals. Two short arias for Sam have now been combined into a single aria opening Act II.

“Most significantly, I have restored three arias that were cut from Act III after the Houston premiere (‘Oh, François, Please’, ‘Dear Loved Ones’, and ‘Stop. You Will Not Take Another Step!’) and reassigned the reading of Dinah’s letter, ‘Dear Loved Ones,’ from Junior to François. This aria has a vital, twinned role in the opera with another I have restored for François, ‘Stop. You Will Not Take Another Step.’ The pairing of these two arias allows François’ role as the outsider in the family to assume a clearer dramatic purpose. The letter song allows Sam and his children to come together in their grief; and François’ fury in his climactic number brings his character into focus as he castigates the family for their refusal to be worthy of their loss, and tears the letter to pieces.”

The full orchestra of the 1983 original version was enormous, with 72 musicians, extensive percussion, electric guitar, and a DX-7 synthesizer. Sid Ramin and Irwin Kostal assisted Bernstein with those orchestrations, as they had done for West Side Story many years before.

Sunderland continues, “My goal was to preserve Bernstein’s intentions for the sound-world and the drama of his music, while using a radically scaled-down orchestra of 18 musicians. To accomplish this I used a somewhat lopsided orchestra, with single players on everything but the clarinets (three) and horns (two) because these two instruments offered me the most flexibility, with wide ranges in pitch, dynamics, and color. The percussion was a particular challenge. This is an opera that opens with a car crash — Bernstein used a wide variety of instruments and timbres to achieve some special effects, as well as a sheer clangorous density of sound. By giving one of the percussion parts over to an extensive drum kit, I have condensed much of the writing, without sacrificing too much of Bernstein’s original intent, allowing two extremely dexterous players to cover multiple parts simultaneously. I have also eliminated the electric guitar and synthesizer entirely, choosing to have a fully acoustic orchestra. This chamber ensemble will not encompass the sheer volume and overwhelming force of the original orchestration, but it instead has a transparency, and an intimacy, that are appropriate to the opera’s themes and its characters, and that allow for a different perspective on Bernstein’s score.

“A Quiet Place is unlike anything else in Bernstein’s catalog, and really, unlike anything else in opera. It contains some of Bernstein’s very finest work (the Postlude to Act I may be the most powerful music he ever wrote) and tackles a challenging subject in a way that is both radical and true, and utterly compelling. Like other works of Bernstein’s later period, it was not appreciated at the time of its premiere for the daring, provocative vision he brought to us, but now we have caught up to him. The opera is finally becoming recognized as the culmination of Bernstein’s many gifts as a composer, a theater artist, and a communicator. Creating this adaptation was a deeply powerful experience for me, and it is my hope that it will provide audiences with a similar experience of this great American opera.”

He specifies that his version is not intended to supplant the earlier: “My adaptation is really an alternate take on the material. Bernstein and Wadsworth created an intimate opera on a grand scale, amplifying the emotional stakes. We felt that it was worth exploring how the opera could be experienced if it was presented on the same intimate scale of its central quartet of characters. When the audience is physically closer to the stage, it allows the actors to give subtler performances. It’s not such a ‘big sing’ — the smaller orchestration leaves more space to allow a singer to be vulnerable without worrying about carrying over 72 musicians in the pit, or worrying if their performance is registering to someone sitting hundreds of feet away. And it allows singers with smaller voices to be cast effectively in the opera.”

This revision is more communicative than the earlier work, which I saw at New York City Opera. Because of its focus on the main characters, and its orchestra of only 18, this A Quiet Place is more intimate look at a troubled family. The vocalizing is in closer synchronization with the orchestra. Theoretically, we may regret the elimination of a large mass of players, but there’s plenty of rich sonority, and individual instruments come through more clearly. Overall, there’s more transparency.

Bernstein’s music is astringent in comparison with his choral and his Broadway compositions, but haunting melodies do exist, plus a couple of catchy showpieces. The latter part of the opera has a pulsating quartet that’s emotionally compelling. The best aria is the query of Dede when she re-visits her late mother’s garden, “Mommy Are You Here?,” gorgeously sung by Ashley Milanese.

Tyler Zimmerman was impressive as the father, Sam. He used his bass-baritone voice richly when he angrily sang to his son “You Shouldn’t Have Come” and touchingly when he returned home after his wife’s funeral and sang that “it’s the same old house” accompanied by brass and reeds. Jean-Michel Richer, a tenor from Montreal, was effective as François, and Dennis Chmelensky’s high baritone voice rang out brightly as Junior, whom he portrayed with punk sassiness. Both showed fine musicianship as they dealt with some super-fast text and tricky rhythms.

The effect was seriously compromised, however, by inauthentic accents. This opera has one character who is specifically French-Canadian but all the others are Americans, and hardly any of them sounded so. Milanese did best, but even she occasionally enunciated like an operatic soprano. Chmelensky’s accent was totally inappropriate. Movie audiences reject performers who get their accents wrong, and properly so. When British and European performers appear on American stages and in films playing American characters, they are rightly criticized when some of their words are pronounced with a foreign accent. The same standard should be applied to performers in an American work like this. It’s just as important to accurately pronounce the words of characters as it is to hit the correct notes.

The direction by Daniel Fish was problematic. The first scene showed everyone at a funeral parlor facing directly at the audience (rather than diagonally as in A Quiet Place’s previous production.) In later scenes the interaction of family members was visceral, but they were on their own, with no scenery or props. Both of these choices prevented the proceedings from seeming real, which should have been a prime goal.

The deceased mother appeared, mutely, throughout. When Dede sang about her mom, old home movies by video designer Jeff Larson were projected on a big screen behind her. The idea was good, but it was prolonged excessively. Corrado Rovaris led the excellent players from the Curtis Orchestra with precision, and with considerable emotion.

A Quiet Place is exceptionally personal. Bernstein married the Chilean-born actress Felicia Cohn Montealegre in 1951. She wrote to him, “If your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depends on a certain sexual pattern what can you do? I am willing to accept you as you are, without being a martyr or sacrificing myself on the LB altar. I happen to love you very much — this may be a disease and if it is, what better cure?”

A Quiet Place connects with multitudes of people who witnessed tensions between parents, and among siblings — even people who did not have Bernstein’s sexual issues. Of course it will especially appeal to those who do have identity questions. And to prurient voyeurs.

Because of that, I should share my personal connection with Bernstein. I am one of the dwindling number of survivors who knew him (although not well) over a period of four decades. And I spoke with people who were close to him since the early 1940s at the Curtis Institute and in New York when he was making a living as a piano teacher out of his second-floor flat in a brownstone on 52d Street west of Fifth Avenue.

Women fell in love with Bernstein. Shirley Gadis, a Philadelphian six years younger than he, said “There’s nothing Lenny can’t do at the piano, plus he’s witty, good-looking, cultivated, bedazzling, hot stuff.” Acquaintances reported that the young Bernstein listened to classical recordings as well as pop records such as Peggy Lee’s “Why Don’t You Do Right” which was one of his favorites, while he drank Scotch at all hours of the day.

Composer Ned Rorem wrote in his diary, “There was no area in which he did not consider himself an authority — pictures, books, politics, cooking, lovemaking.” Others said that it was charming, but irritating, how LB was an expert in so many fields and gleefully attacked people who had differing opinions. I saw a bit of that after a concert he led at Villanova University with the New York Philharmonic in 1966. A student told Bernstein that Mahler’s music eluded him, and Bernstein lashed out at the youngster, with wit, and we laughed, but he could have shown some kindness.

Director Harold Prince told me, “Critics say that he spread himself too thin, but I disagree. When you’re so good as a pianist, conductor, writer, teacher and composer of classical and show music, why shouldn’t you do everything? If you can do it all, why not?”

I met Bernstein in 1957 when West Side Story was in its pre-Broadway Philadelphia engagement and I was a student at Temple University and station manager of WRTI-FM. Our connection was librettist Arthur Laurents, whose cousin was one of my best friends. Bernstein’s erudition, high energy and enthusiasm impressed me tremendously. In later years, I interviewed Bernstein for broadcasts on National Public Radio.

We now know that he left his wife to live with a man in 1976, but returned to Felicia when she was diagnosed with cancer. I spoke with him during those days and it was clear that he dearly loved her. But he seemed depressed, fatigued and troubled, with a much different personality than earlier. It is this later Bernstein who wrote A Quiet Place.