Three quarters of a century ago, in 1941, a musical experiment ended — killed off by the very conflagration that brought it into being.

This was the All-American Youth Orchestra, founded in 1940 by Leopold Stokowski to combat the rise of anti-American propaganda by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

At that difficult moment in history, Stokowski assembled a new orchestra with a nucleus of eighteen experienced Philadelphia Orchestra players and eighty young players between the ages of 15 and 25. The project was designed to prevent South American countries from allying themselves with Adolph Hitler.

In 1939, the year that war started in Europe, theatrical producer Jean Dalrymple went on a tour of Latin America with pianist Jose Iturbi in his single-propeller private plane. She told me in a taped broadcast, “I found that Italy had sent over the La Scala Opera to Buenos Aires and the Italian embassy was giving the most marvelous open parties for all of the opinion makers of the Argentine, and everybody was saying ‘Oh, these Fascists are wonderful people.’ And then I got to Santiago Chile and Germany had brought their Staatsoper and the German embassy was open and all the opinion makers were there and they were saying ‘These Nazis are wonderful people. Look at these great artists they have.’”

Dalrymple called Secretary of State Cordell Hull and urged him to send something cultural to South America because the Nazis and Fascists were ingratiating themselves with Latin Americans who thought that the USA knew nothing beyond “how to erect skyscrapers and build automobiles.” Hull arranged for a goodwill musical mission and the platinum-haloed Stokowski leapt at the opportunity. He was the co-conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra, sharing that post with Eugene Ormandy and spending half of each year in Hollywood (Fantasia was his latest film) — but Stokowski was restless and looking for new adventures.

He hired players for the All-American Youth Orchestra with no discrimination as to gender or color. In the summer of 1940 they sailed to South America and gave concerts in Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo, Buenos Aires, Rosario, Santos, Sao Paolo, Port-au-Spain and Trujillo City. When they returned triumphantly to the United States they gave concerts at Constitution Hall in Washington, Carnegie Hall in New York and the Academy of Music in Philadelphia.

A second season in 1941 saw a transcontinental tour of 32 cities in the United States and Canada, personally financed by Stokowski, that introduced symphonic music to many towns that had no such orchestras of their own. He planned another for 1942, through Mexico and down the Pacific coast of Central and South America. But before the dawn of that year Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor plunged the USA into war. The army began drafting many of the young musicians, non-military travel was restricted and gas was rationed, which thwarted the orchestra’s touring plans and caused its demise.

Ironically, while the mission of the orchestra was to strengthen the United States’ position as World War II was beginning, the orchestra was forced to disband because of that war.

During the brief existence of the All-American Youth Orchestra, it made recordings for Columbia, which financed the first trip. About half were made in Buenos Aires during the summer of 1940; some in New York that year and others in Hollywood at the end of the orchestra’s cross-country 1941 tour.

The Music & Arts label has released all of them on a group of CDs, and they reveal playing that’s on a level with the top professional symphony orchestras, with the added ingredients of freshness and spontaneity.

Critic Henry Pleasants wrote at the time that “the ensemble has a unanimity and precision hardly surpassed and not often equaled by the foremost organizations. There is vitality aid enthusiasm here, flexibility and responsiveness.”

The youngsters, and even the older musicians, played their hearts out because (a) they felt honored to be selected for the orchestra and (b) they were representing their country at a time of peril. Most of them were in awe of their leader, who was the most glamorous of all symphony conductors. They also had fear. Unbound by annual contracts or union rules, anybody could be discharged by being given an extra week’s wages and their ticket home.

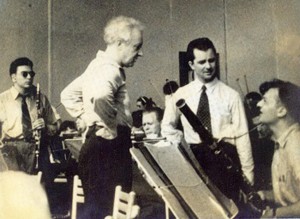

The personnel changed somewhat in the orchestra’s second year, as some of players chose to, or were told to, return to their schools. On the right, Stokowski with some of those players. 21-year-old French horn Mason Jones is seated directly in front of Stokowski:

Several of the pieces in these albums were never recorded by Stokowski any other time during his long career, including a passionate Sibelius Symphony #7 in C major. The piece remains essentially in one key throughout and relies on coloristic changes. Stokowski’s players bring out those rich sonorities. The soft chords by divided strings about four minutes before the ending are especially memorable.

Ravel’s Bolero is also a one-of, which is surprising because he started conducting that showpiece in 1930 with the Philadelphia Orchestra; he included it in a planned 1939 concert for electrical instruments, and I heard him lead it with the American Symphony Orchestra in New York in the late 1960s, yet he made no other recording of it.

One of my favorite selections is a Brahms Symphony #4 that’s especially relaxed and lyrical, almost like chamber music. The players seem to be intently listening to each other and reacting with collegial warmth.

Richard Strauss’s Tod und Verklarung (Death and Transfiguration) was one of the last recordings they made together and the strings produce an eerie tone, as if the color is sapping from the players’s faces as life drains from their bodies.

Familiar symphonies like the Brahms First, Beethoven Fifth and Dvorak New World provide interesting comparisons with recordings he made previously with the Philadelphia Orchestra and later with other orchestras. The Brahms has an especially slow pacing of the first two movements.

Peter and the Wolf, with Basil Rathbone narrating, is a treat. Stokowski wrote a new, colloquial English translation of Prokofiev’s Russian text, which Rathbone described (to me in a 1967 interview) as “much less ham” than other versions. The instrumental solos introduced players who went on to careers in the first chairs of major orchestras.

The bird was played by the flutist Albert Tipton who became soloist with the Detroit Symphony, the duck by the oboist Harold Gomberg who became soloist with the New York Philharmonic, Peter’s grandfather by the bassoon Manuel Zegler who took that chair with the New York Phil, the wolf by French horns James Chambers and Mason Jones, who became first chairs with the New York Phil and Philadelphia Orchestra. Although experienced Philadelphia Orchestra first desk players were in the AAYO (such as bassoonist Sol Schoenbach and harpist Edna Phillips) , Stokowski instead chose youngsters for those roles.

It’s great to have a chance to hear American contemporary pieces featured during the tours, such as Morton Gould’s “Guaracha” from his Latin-American Symphonette, the Scherzo from Paul Creston’s Symphony #1, and Henry Cowell’s Tales of our Countryside. Cowell traveled and played piano with the orchestra.

To the left: Stokowski talks with hornist Mason Jones and bassoonist Sol Schoenbach.

The Youth Orchestra version of the Tristan und Isolde Love Music is an arrangement of music from Acts 2 and 3 of Wagner’s opera, somewhat different from other Stokowski versions. During rehearsals, Stokowski told his young players to try to imagine the passion of an extra-marital affair, so we listen to the results with inquisitiveness. (Presumably, when he led this music with older orchestras, the players had more first-hand insight.)

Some of the selections had popular appeal and they fit on one side of a 78-rpm disc, such as Rimsky’s The Flight of the Bumble Bee, Novacek’s Perpetuum Mobile, Falla’s Ritual Fire Dance, and Schumann’s Träumerei.

When I produced a radio series about Stokowski, I found that the sound on the original Columbia 78s was substandard, probably because that company had less experience than RCA Victor in symphonic music, and because the wartime 78s used poor quality shellac. Therefore it’s a delight to hear how well producer Mark Obert-Thorn has restored and improved the material.

A couple of these recordings were not issued at the time: Brahms Symphony #1 and Sibelius Symphony #7, the final published symphony by that composer. Obert-Thorn masterfully transferred the music from unpublished vinyl 78-rpm test pressings.

Post-mortem: The board of the Philadelphia Orchestra was angry that these recordings on the Columbia label were hurting sales of Philadelphia Orchestra RCA Victor discs. Samuel Rosenbaum, vice president of the board, told me: “Royalties from recordings represented a major part of our income. The majority of the board decided that this was intolerable.” So on December 11, 1940, the board voted to end its association with Stokowski .

These, then, are CDs of great historic and musical importance.

The material is distributed over several Music & Arts CD sets: Leopold Stokowski with the All-American Youth Orchestra (filled out with nine selections by Stokowski and the Hollywood Bowl Symphony), Stokowski Edition X, Stokowski Edition XII, and Stokowski Edition XV.

Details are at http://www.musicandarts.com/

Above, the orchestra in its first year, 1940.

Please share your thoughts with us. Address to editor@theculturalcritic.com

Read other reviews on The Cultural Critic