Originally published in The Opera Critic, the international website for professional musicians.

The new production of Wozzeck at the Metropolitan Opera presents a stark contrast with the American premiere of that opera 89 years ago.

Leopold Stokowski conducted that debut in Philadelphia’s Metropolitan Opera House and at New York’s old Metropolitan Opera House at 39th and Broadway. Yannick Nézet-Séguin leads the new production, and the fact that both he and Stokowski were music directors of the Philadelphia Orchestra is an interesting coincidence.

(The Philadelphia Met was built by Oscar Hammerstein in 1908, two miles north of the Academy of Music. When it opened it was the largest theater of its kind in the world, seating more than 4,000 people. It was recently restored and the Academy of Vocal Arts will soon present the house’s first opera performance in more than a half century.)

Aside from that coincidence, other aspects of Wozzeck are vastly different from one another. One, the number of musical personnel; two, the visual appearance of the productions. Let’s take a look at that long-ago American premiere, based on a series of interviews I conducted with participants.

In 1931, 116 members of the Philadelphia Orchestra were in the pit, plus 25 students from the Curtis Institute of Music as an on-stage band. In 2020 there are 91 musicians in the pit plus six more on stage. This is a startling disparity when you realize that 1931 was the depth of America’s economic Great Depression yet funding was provided for the enormous forces by the boards of the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Curtis Institute.

The appearance of the productions is the most obvious difference. William Kentridge’s 2019 design includes barbed wire, gas masks, massive wreckage, and flickering projections, all intended to depict the chaos of World War One. I have admired Kentridge’s artistry, but in this case he has needlessly cluttered the stage and distracted us from the personal plight of the pathetic, haunted title character.

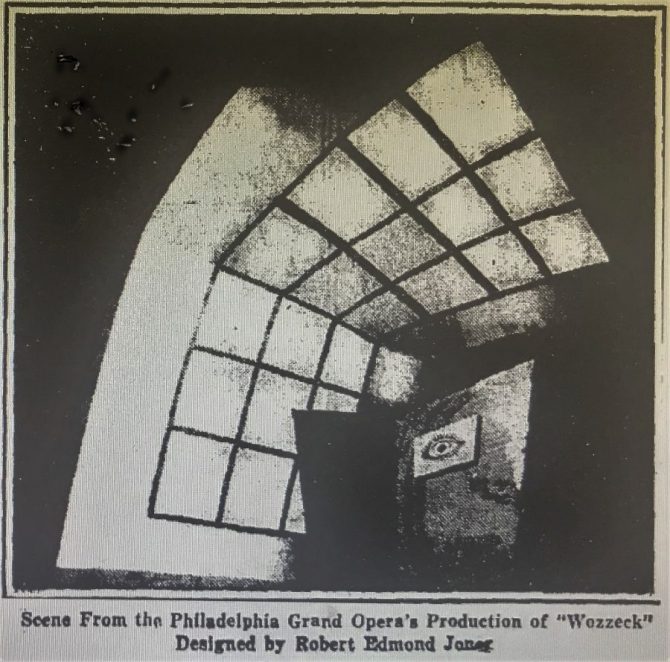

The designer of the American premiere was Robert Edmond Jones, known as the partner of Eugene O”Neill on Anna Christie, The Great God Brown, and Desire Under the Elms. Very few images survive of his Wozzeck production, and one of them is at the top of this article. (See above.) As you can see, it is starkly simple.

The 1931 staging used reflections to suggest the water which symbolizes the instability and dissolution of Wozzeck’s world. Berg wrote music that depicts Wozzeck wading into the deepening water of the pond to get rid of his murder weapon. You might expect his sinking to be described by descending musical figures as he goes deeper into the pool. Instead, we hear ascending scales that show us Wozzeck’s perspective of the water rising around him as he drowns.

The Kentridge production eliminates the water altogether, as well as the poignant view of Wozzeck’s son being taunted by his friends at the opera’s end.

Fortunately, I was able to learn a lot about the 1931 production by speaking with key personnel for broadcasts on National Public Radio. Stokowski described Jones’s concepts to me:

“The first scene was in a doctor’s office in the army and Robert Edmond Jones had a big chair in which the victim of the doctor was seated and in the background was hanging a skeleton. He lit that skeleton from the ground with very powerful green light. The other side of skeleton was a white screen on which was the shadowy form of the skeleton in purple. There’s, later, a scene where Marie is sitting in her room, a very poor room, reading the bible and rocking her baby at the side. In the score is a description of that room with a window at the back and then a door and the cradle of the baby and table on which is the bible.

“Gradually we put away all those not very interesting details and what finally happened was one of the greatest scenes I’ve ever seen on the stage. We took a desk from the orchestral players, put on it a telephone book, and on the ground was one small spotlight and a chair for Marie to sit on. There was no cradle, no baby. There was no light except that one light from the spotlight. You saw merely the top of the book which was supposed to be the bible. You saw the head of Marie and her left arm swaying the cradle of the baby, in imagination because it was not there. Now that whole scene finally cost about two dollars.”

Stokowski said, “Instead of scenery in the accepted sense, there were radical lighting effects, with black outs at the end of scenes. Thus we were able to dispense with intermissions, presenting all fifteen scenes without so much as a single entr’acte, something not previously attempted.” [The world premiere in 1925 in Berlin was in three acts separated by intermissions, and so were most productions until 1980 at the Met, conducted by Levine.]

Jones’s production focused on the injustice and poverty pervading the world. Stokowski said, “It is an apotheosis of an age-old theme — the exploitation of the under-man by the upper-man, the pathos of simplicity and credulity in the hands of callous intelligence. It is an outcry of the oppressed through all time, clothed in a simple story. But that story is presented as a vision and with tremendous vividness. With its swift scenes it is like a thin knife cutting a cross-section through universal experience. Yet the greatest thing about the work is the sense of pity and understanding of oppressed humanity it displays.”

Other musicians corroborated Stokowski’s description. One of my most interesting conversations was with Nelson Eddy, who had sung Amonosro, Papageno, Wolfram, Gianni Schicchi and other opera roles in Philadelphia:

“I auditioned for Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder for Stokowski. He signed me up and as I was going out the door he said ‘By the way, you don’t know Wozzeck do you?’ And I said ‘Yes.’ And he was surprised and I said ‘I learn everything that I hear you’re going to do, just in case I’m asked to do it.’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘this I must hear.’ So we went through the role of the Drum Major in Wozzeck and he said ‘You’ve got that job too.’ That was my first and only performance in a staged opera in New York.”

Soon after, Eddy re-located to Hollywood and became a movie star. “Then things changed and I had to sing songs like ‘Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life’ and ‘Rose Marie I Love You’ and these songs were forced on me ever since.”