Mahler: Symphony No. 3. Yannick Nézet-Séguin leading the Philadelphia Orchestra, May 2017.

Although not frequently performed, Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 is the piece which best exemplifies his life and career. Yannick Nézet-Séguin led a magnificent performance of it during the closing week of the Philadelphia Orchestra’s 2016-17 season.

His Symphony No. 3 contains Mahler’s greatest balance between anguish and love and its finale is optimistic. This is in contrast to the gloom of Mahler’s later works when he confronted his own failing health, the death of his young daughter, and the infidelity of his wife.

With a huge orchestra plus the calm presence of mezzo-soprano Karen Cargill, 33 members of the American Boychoir and 38 women of the Philadelphia Symphonic Choir, this was one of the most impressive Philadelphia concerts in recent memory. Without an intermission, the piece ran 1 hour and 44 minutes. The 35-minute first movement, by itself, was longer than most of Beethoven’s complete symphonies.

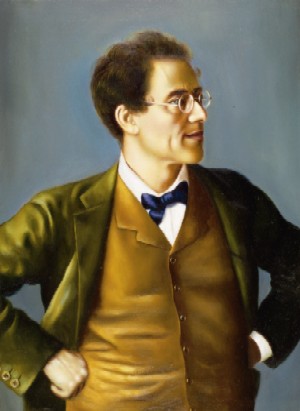

I admire Mahler and identify with him because one side of my family, like his, was Jewish from Central Europe. I have enjoyed spending time in his Bohemia birthplace and in the Vienna where he became famous. Yet I am sometimes put off by his overwhelming angst. He claimed that his music represents “the whole world.” Mahler seems, instead, to represent a grim and morbid view of earthly existence.

Mahler was self-absorbed, and repeatedly thought about what nature meant to him: “What the flowers in the meadow tell me. What the creatures in the forest tell me. What love tells me.” Mahler labeled his symphonies with those details. This is not criticism but, rather, an observation of what made Mahler unique. Beethoven put objective labels into his Symphony No. 6: “Scene by the brook. Thunder storm”, etc., whereas Mahler’s were much more personal. This enthralled some listeners while it alienated others.

He was resisted in his own time partly because he was an outsider from the provinces and a Jew; and additionally because his music was permeated by his personal anxieties. He went against the grain in an era where society, unlike Mahler, was confident. Stefan Zweig, in his book The World of Yesterday, described Europe in 1914: “There was progress everywhere—new theaters, libraries and museums, new cultural forms. What could interrupt this rapid ascent, dampen the elan which constantly drew new force from its own story? A wondrous carefree spirit reigned.”

The world was euphoric in the Roaring Twenties. The 1930s, despite the Great Depression, were permeated with Rooseveltian optimism. The 1939 World’s Fair touted “The World of Tomorrow.” The end of World War II was triumphant. Rhapsodizing about the atomic age, the Las Vegas Review-Journal printed that mankind might be “on the threshold of one of those new eras which was ushered in by the invention of the steam engine.”

With the birth of the Cold War, people realized that such optimism was misplaced. Poet W. H. Auden in 1947 wrote about “The Age of Anxiety” and Leonard Bernstein wrote a symphony with that title. In that milieu, Mahler’s symphonies gained popularity and Bernstein became Mahler’s most visible champion.

After the Philadelphia Orchestra concert, I re-watched the video of Leonard Bernstein conducting the Mahler Third with the Vienna Philharmonic and, even though Bernstein is indelibly identified with Mahler, Yannick’s rendition was more passionate; the sound of the Philadelphians was bolder. In particular, Yannick’s tympani had more power, his horns more sonority and his strings more presence. This was a historic performance. Hopefully the world will get a chance not only to hear, but to see video of this.

The Third starts with a fanfare by eight massed horns, interrupted by blistering tympani. Mahler called this movement “A Summer Morning’s Dream” and his view of summer was darker than what we normally associate with that season. Mahler’s paean to summer was full of clashing colors and dissonance, illustrating the primordial stirring of nature. Later, a solo violin portrayed the chirping of birds. We heard a notable trumpet solo by David Bilger, and a series of joyous marches.

Mahler wrote about the next part: “Eternal love spins its web within us, over and above all else.” Yet, in the midst of it, he felt self-pity and asked us to “Behold the wounds I bear.” Writing a calm and nostalgic scherzo section, Mahler said he was thinking of a poem by Nikolas Lenau in which a man contemplates his dead friend and “we once again feel the shadow of lifeless nature.”

George and Ira Gershwin wrote a sad song that said, “I’ve found more clouds of gray/Than any Russian play could guarantee.” Maybe they should have used “any Mahler symphony” as their analogy. My advice is to set aside Mahler’s comments and concentrate on the music.

The brief mezzo-soprano solo by Cargill includes the words, “I have broken the Ten Commandments. I must go away and weep bitterly.” A chorus of women answer, “Pray to the Lord. Love only the Lord. Thus you will attain heavenly joy!” These Christian pronouncements were added just before Mahler converted to Catholicism, to silence critics who opposed his hiring as music director at the Court Opera in Vienna.

The closing movement is a slow adagio with a comforting melodic line. A majestic chorale of brass instruments rises to a triumphant finish. A special moment was the pregnant pause before the quiet entrance of the cello section about an hour and a half into the symphony. In the protracted D-major final chord, intense string playing was on an equal intensity level with a huge brass chorale. We saw fiddlers sawing intensely, criss-crossing and overlapping each other. This is a technique which Leopold Stokowski introduced when he was music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra, to produce fuller sound, but we rarely see it these days.

As the late violinist Herman Weinberg told me, “Before then, all string players bowed up and down in synchronization with their section leader. Stokowski had us bow independently.” And conductor Francis Madeira told me, “Use plenty of bow when you want a tremendous amount of what you might call ‘juice’ and when you run out of bow, change it.”

This produced extraordinary volume and length during Nézet-Séguin’s final chord. Other outstanding solos were by flute Jeffrey Khaner, horn Jennifer Montone, oboe Richard Woodhams (especially when accompanying the mezzo aria) and trombone Nitzan Haroz (plus trumpet Bilger whom I saluted earlier).

After the symphony came an addition which deserves high praise for its concept, but criticism for its execution. A postlude organ recital was scheduled, utilizing different soloists and compositions on different nights. At the performance I attended, Jeremy Flood beautifully played a Prelude and Fugue by J. S. Bach (BWV 541) that was in the same G-major key as Mahler’s symphony, followed by a Brahms Organ Prelude that quoted a tune from the fourth movement of Brahms’ Symphony No. 1, a melody also referenced by Mahler. This was a great idea.

On the other hand, the symphony ended at 9:52 p.m. and organist Flood did not come onstage until 10:19. Many attendees complained that they couldn’t wait around that long, and left. The long pause broke the mood and was an unnecessary imposition on audiences’ time.

This review originally appeared in DC Metro Theater Arts

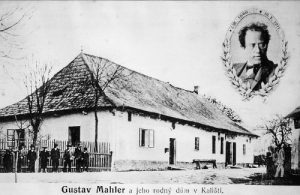

On the right, Mahler’s birthplace in Bohemia