Giordano: Andrea Chenier, Gran Teatro del Liceu, Barcelona, March 2018

Andrea Chenier is an unfairly disparaged opera. This production, imported from Covent Garden to Barcelona, reveals that it can pack a wallop when the three leads are well cast.

Jorge de León, Sondra Radvanovsky and Carlos Álvarez make it a thrilling event. They play a poet who inspires the French Revolution then is destroyed by the mob’s insatiable appetite, the heiress who falls in love with that poet, and a servant who rebels against his masters and becomes head of Robespierre’s bloody tribunal. Reportedly the alternate cast, starring Jonas Kaufmann, Julianna Di Giacomo and Michael Chioldi, was just as effective.

Many of Chenier’s elements deserve praise, such as its last-act farewell by the jailed tenor as he awaits his death (which pre-dates a similar scene in Tosca) and a stirring peroration at dawn that has even more defiance and grandeur than Tosca’s ending. A mob confronting high-society partygoers, and a raucous courtroom scene also have great theatricality.

Andrea Chenier centers on the title character which can be sung in markedly different ways. Kaufmann, by most reports, sang with darkened, covered tones, while I heard de León use red-meat Italianate technique. A 42-year-old tenor from Guatemala, de León has a stodgy appearance but has exciting squillo. Differences were ever thus. In early years the role was performed by Otello voices such as Tamagno and Zenatello. Caruso was to have starred in Chenier’s Met premiere in 1921 and, after his death, was replaced by Beniamino Gigli, who used a more honeyed style to great effect.

In my own time, Mario Del Monaco made the role his own with clarion projection, yet I also attended a beautiful performance by the sweeter Carlo Bergonzi. Richard Tucker and Franco Corelli encompassed both sides of the character quite well. More recent interpreters such as Domingo and Pavarotti lacked the ideal combination of heft and ping. De León, to my surprise and pleasure, comes very close to perfection. His tones are focused and bright and he also uses suave portamenti on phrases in the Act II love duet and “Come un bel di di maggio.”

The baritone role of Carlo Gérard also holds great rewards. He is a lowly servant whose father is a lackey for the aristocratic de Coigny family. He has a crush on the teenaged Maddalena de Coigny who, in turn, is enamored of the poet Chenier. Gérard tears off his livery and leads a rebellion against his employers. He becomes a leading official in the Revolution where he wields control of the life of his romantic rival. In “Nemico della patria?” (“Enemy against his country?”) Gérard anguishes that he used to be a slave of the nobles and he’s now a slave to his own lust. Clearly, Gérard is a much more complex and interesting villain than Scarpia.

Álvarez, from the Andalusia region of Spain, is a mature artist who still has beauty of tone and penetrating power. He almost steals the show with his conflicted feelings and beautiful singing. Multiple sources tell me that the young American baritone Michael Chioldi did just as well when he was in the cast.

Maddalena de Coigny is not as extensive a role, yet it’s been a vehicle for Rosa Ponselle, Zinka Milanov and Maria Callas. No soprano has put a stamp on it in recent years — until Radvanovsky here and now. This is no surprise to me, because I saw her do a fabulous “La mamma morta” in recital in Philadelphia last season. The tall and majestic Radvanovsky makes a strong impression in her other big scenes, the Act II love duet and Act IV confrontation with the guillotine, “Vicino a te s’acqueta.” Her voice has warmth and depth, yet there’s room for improvement with more subtle floating of the pianissimi on “Ora soave, sublime ora d’amore.”

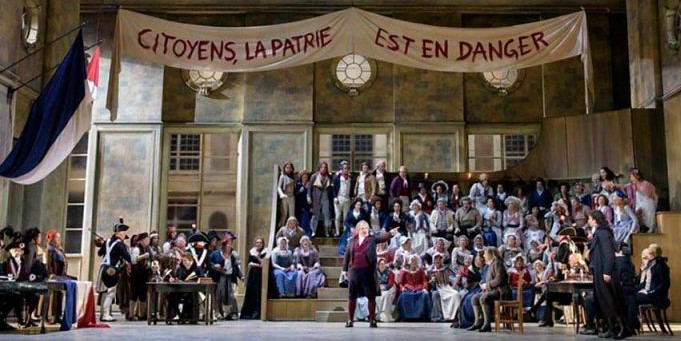

The opera makes a visceral connection with the audience despite a superficial, too-pretty production by David McVicar with sets by Robert Jones. Their Act I de Coigny salon accurately displays decadent luxury with perfumed wigs and prissy dance steps, but subsequent acts fail to show starkness or danger. Especially egregious is Act IV which, in other productions, reveals a prison or the shadow of the guillotine. Here we see a city street and when the lovers go to their deaths it looks like they’re taking a casual stroll down the boulevard.

In supporting roles, the Argentinian baritone Fernando Radó is appealing as Chenier’s friend, Roucher; Manel Esteve is excellent as the revolutionary Mathieu; David Sánchez is a scary Dumas; Francisco Vas is a fine character performer as the spy Incredible; and Sandra Ferrández is an entitled Comtesse. In her scene we see how cleverly Giordano illustrated the imbalance between the haves and have nots by assigning rococo elegance to the aristocrats and giving the servants contrasting forceful music.

77-year-old Anna Tomowa-Sintow, who long ago sang Maddalena, makes a nostalgic reappearance as the blind Madelon who enlists her grandson in the Revolutionary army. Pinchas Steinberg leads the orchestra with nice sensitivity to the singers, but insufficient fury.

This review originally appeared on the international website The Opera Critic.