The Broadway show by William Finn, The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, has charmed audiences in many productions over the past ten years, and his Falsettos won Tony Awards for Best Music and Lyrics in 1992.

Between these two hits came a relatively obscure Finn musical that debuted at Lincoln Center in 1998 but never got to Broadway nor had a national tour. Yet, I submit, A New Brain is Finn’s masterpiece.

The 11th Hour Theatre in Philadelphia recently presented the original Lincoln Center version of this show in three performances over one weekend, and then Encores! in New York City produced a revision newly edited by Finn and James Lapine, and directed by Lapine. Both presentations, in tandem, confirmed my opinion.

The origin of the show was a real-life drama. In June of 1992, one week after Finn received his Tony Awards, he collapsed at a restaurant across 45th Street from the theater where Falsettos was playing. Rushed to NYU Hospital, it was feared that he had either a stroke or aneurism. (In 1996 an aneurism took the life of composer Jonathan Larsen just before the premiere of his Rent.)

After tests, the 40-year-old Finn was diagnosed as having a malformed artery in his brain, leaking and ready to burst. He lay in a coma with his mother, lover and friends at bedside. High-risk cranial surgery was his only hope. When Finn regained consciousness he began writing songs about his experience. This evolved into a humorous exploration of crisis and recovery and it reveals his biggest terror about possible death —- fear that he’ll never be able to finish the music that’s inside him.

The central character of Finn’s show is Gordon Schwinn, a frustrated children’s TV songwriter who almost dies from a brain leakage.

Beyond that specific crisis, however, A New Brain will resonate with every self-doubting man or woman who’s beset by obligations, overwhelmed by life’s events and wondering whether he or she will ever achieve anything. Gordon is plagued by twin fears: not just that he will die, but that if he lives, he won’t be the same man he was before.

If all you know of Finn’s music is the lighthearted Spelling Bee, you owe it to yourself become acquainted with A New Brain, which is light-years more emotional and complex. This show relates to peoples’ lives even more than Falsettos, which depicted a gay man leaving his wife and son, and then the death of his lover from AIDS. A New Brain resonates for anyone who feels inadequate or unfulfilled (isn’t that all of us?) and those who have faced life-threatening illness. His protagonist, like us, wonders what part of him — or what creation of his — might live on after death. To me, the show is about creative frustration and all the songs we never get to write, whether it be because of illness or emotional blocks or procrastination.

A New Brain contains an unusually wide range of song-types, including doo-wop, pop love songs and tango. Two of the ballads live on in cabarets and on records: “I’d Rather Be Sailing (and then come home to you)” and “The Music Still Plays On.” What’s more, there’s linkage between songs that appear early in the play and reappear later in transmuted form, matching the transformation that the composer personally underwent.

Near the start of the play, the protagonist sings “You’ve got to have heart and music to make a song,” a hand-clapping, finger-snapping rouser. At the end he thankfully sings that he’s been given “time and music to make a song.”

While the tunes are easily accessible, the lyrics were mystifying to some observers. They couldn’t understand why various characters sang negatively about the protagonist. I interpret this as the song-writer’s hallucinatory ideas, during his illness, of what he imagines to be his loved-ones’ feelings about him. One example is when his mother sings a lament in the past tense. It is the writer’s imagining of what his mom will say if he doesn’t survive the surgery.

Another disturbing song is “Whenever I Dream,” about creative block, stating that when you dream you’re free but when you awake you’re limited by your fears. Finn and Lapine elected to cut this number from their revised version, and I lament its loss.

Another cut was “Eating Myself Up Alive” in which Schwinn’s overweight male nurse sang about his own apprehensions. The lyrics, of course, reflect Finn/Schwinn’s anxieties and his problem with over-eating.

The most obvious cut in this revival was right after the opening when Schwinn went to lunch with his friend Rhoda, complained to her about his job and his boss, then collapsed over a platter of ziti. (In real life, Finn collapsed on the sidewalk outside an Italian restaurant.) The object, clearly, was to get more quickly into the brain crisis and to trim the show’s length, and this change is a dramatic improvement.

I recall the truly original version of A New Brain that I had the privilege of attending in workshops in the years before the Lincoln Center premiere. And this illustrates the art of creating and revising a show.

The field of classical music has a tradition of preserving every note ever written by Beethoven, Verdi, et al. Recordings are made that include alternate versions of operas, even scenes which were cut by the composer. I’d like to see that with A New Brain — a video or at least an audio preservation of the urtext.

Finn’s first draft started with him in bed with his lover Roger, munching cookies. We learned that he had a weight problem; Roger teased him about it. Best of all, we witnessed the loving relationship of two gay men (a rare thing to see on stage in the 1990s.) In this setting, Roger sang the beautiful ballad “I’d Rather Be Sailing,” complete with some additional words and music.

Utilizing Lapine’s talent for shaping a play, Finn agreed to remove that scene. As a result, “I’d Rather Be Sailing” appeared as Finn awaited surgery and friends and family wondered where Roger was. He suddenly appeared, singing the song, which drew laughs from the audience. This was an unfortunate re-positioning. The song was reprised later in the show, more romantically.

Finn himself was heavy, and the script made several references to that fact. But it’s hard to find attractive singer-actors who are overweight. Handsome and slender Malcolm Gets was the original interpreter of the role and the slim Jonathan Groff played him at Encores! Therefore the issue of over-eating had to be downplayed.

In early workshops, the composer Schwinn complained about having to write silly ditties about frogs and spring for his employer, who is the host of a kids TV show, but we never met the man. Later in the creative process, Lapine suggested making him appear in a TV frog costume, personifying Schwinn’s fear. It was a brilliant stroke to present the boss as a comic hallucination who is invisible to all of the characters except the songwriter. Mister Bungee became the negative voice inside the songwriter’s mind, portrayed by the wonderful Chip Zien.

And Finn added a song for Mister Bungee which Schwinn hears in his head as he wakes from surgery, a song that tells him “Don’t Give In” and indicates that he has turned the corner mentally and physically. These changes add an extra dimension to the show.

The 1998 production was preserved by RCA Records, conducted by Ted Sperling with orchestration by Michael Starobin and featuring Gets, Zien, Norm Lewis as Roger, Penny Fuller as Schwinn’s mother, Mary Testa as a homeless woman and a fledgling Kristen Chenoweth as a waitress and a nurse. A talented array of women have played the mother, from Nancy Dussault in workshop to Ana Gasteyer at Encores!

The low-budget 11th Hour presentation shows that A New Brain is an economically-feasible property. It deserves wider circulation among regional theaters, and some day I hope to see it back on stage in New York City.

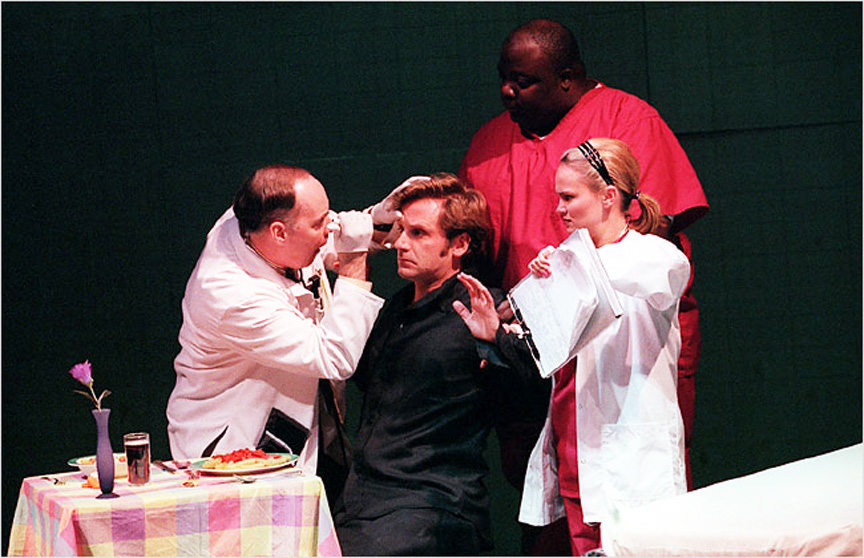

below: Bill Finn