One Woman in a Hundred: Edna Phillips and the Philadelphia Orchestra by Mary Sue Welsh. University of Illinois Press, 2013.

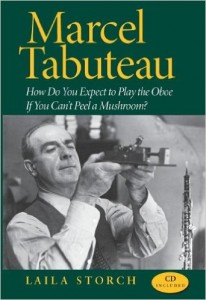

Marcel Tabuteau: How Do You Expect to Play the Oboe If You Can’t Peel a Mushroom? by Laila Storch. University of Indiana Press, 2008.

Edna Phillips was described in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin as “like an illustration on a magazine cover… the typical American girl with plenty of light, golden curly hair, shining brown eyes, the peaches and cream complexion of sixteen, and full red lips.”

To those of us who knew her later, this isn’t quite what we saw. The Philadelphia Orchestra’s first harpist was attractive in a patrician way. Her persona was elegant and reserved.

“I did my best to look as much like a man as possible,” she told me. “At the first concert I wore a very somber black crepe dress with just a little white ruching, monastic looking, almost. In fact, one nice subscriber said she had to look twice to make sure it was a girl.”

So I was shocked to read in Mary Sue Welsh’s new biography that Phillips was subjected to sexual harassment in her first musical job (in the pit at New York’s Roxy Theatre), and that the Philadelphia Orchestra’s iconic conductor Eugene Ormandy propositioned her.

Phillips was the first female player in any major symphony orchestra. The always-daring Leopold Stokowski hired her in 1930, when she was 23, and sat her at the front of the stage, not toward the rear as was the norm for harpists in other orchestras (including the Philadelphia today). She hung on Stokowski’s every word and gesture: “If you looked away you missed something. Under him, the Philadelphia Orchestra sounded like whipped cream, the richest kind of cream in the world.”

Or as she told me, “He taught me to stand on my head and do the impossible.”

In 1933 Phillips married the vice president of the orchestra’s board, attorney Samuel R. Rosenbaum, who also was vice president of Albert M. Greenfield’s real estate company. During World War II, when Rosenbaum served in the army overseas, Ormandy (himself married) made amorous advances towards Phillips so overtly that her fellow musicians believed an affair was actually taking place.

Biographer Welsh confronted Phillips and bluntly asked if she’d slept with Ormandy. “That worm?” Edna replied. “You think I’d give in to him after resisting the glamorous one?” — that is, Stokowski.

In addition to these salacious passages, Welsh’s book is filled with substantive detail about the life of a serious musician, along with anecdotes about colorful guest conductors like Thomas Beecham and Otto Klemperer, and composers like Samuel Barber and Benjamin Britten. Phillips’s biography becomes a history of the Philadelphia Orchestra from Phillips’s perspective. It’s also a paean to an age when instrumentalists and baseball players alike remained in their home city for their entire lives.

Phillips retired from the Orchestra in 1946 but returned for special events, commissioned new works for harp, and chaired the Bach Festival of Philadelphia. Welsh was the Festival’s executive director of the Bach Festival when Phillips was chairperson. Phillips died in 2003 at the age of 96.

Even after Phillips and two other women were hired by the Philadelphia Orchestra in the 1930s, Curtis Institute resisted admitting female wind players because they had little chance of finding work after graduation. With reluctance and with disdain for her gender, the Philadelphia Orchestra’s first oboist, Marcel Tabuteau, finally accepted Laila Storch as a student at Curtis in 1942. Now Storch has written a highly personal biography of Tabuteau, a mainstay of both the Orchestra and Curtis from 1916 to 1954.

Their love-hate relationship makes fascinating reading, especially when read in tandem with Welsh’s biography of Phillips.