Maroons: The Anthracite Gridiron by Ray Saraceni; directed by John Doyle and Randall Wise. Iron Age Theatre through November 27, 2011 at the Centre Theater, Norristown, PA

Once again, Iron Age Theatre has presented a world premiere of a historical play about sports. DW Gregory’s Molumby’s Million, two years ago, concerned rampant speculation over a Montana prize fight in the 1920s; Ray Saraceni’s Maroons is about pro football in the 1920s.

The playwrights are different, but each captured a distant time and place and illuminated social conditions while telling action stories about athletes. Both were directed by John Doyle, the company’s artistic director.

Saraceni is a Philadelphia-area actor who recently played the creepy role of a mass murderer in Christie in Love for Iron Age Theatre. In Maroons he writes about the harsh working conditions endured by anthracite coal miners who lived in and around Pottsville, PA. No wonder that townspeople turned to football for diversion and hope.

The Pottsville Maroons joined the National Football League in 1926 and achieved the best won-lost record for that season but were stripped of the league championship on a technicality. To Saraceni’s great credit, he has turned that technicality into a dramatic climax.

The team’s owner, John Streigel, arranged an exhibition match with a team made up of former Notre Dame players, called the Notre Dame All-Stars. Since Pottsville’s Minersville Park had a capacity of only 6,000, Streigel booked the much larger Shibe Park in Philadelphia for the big game.

But Philadelphia was within the designated territory of the Frankford Yellow Jackets, and that team complained to the league. The league’s commissioner warned Streigel that Pottsville’s franchise would be suspended if the game was played in Philadelphia. Unwilling to pass up a potential financial windfall for his team, Streigel went ahead anyway, and, as promised, the league punished Pottsville.

En route to that climax, Saraceni wrote a compelling story about how football became an outlet for the aspirations of working-class people.

The drama is leavened by the presence of several atypical characters. One is the team’s coach, a Penn State grad who loved ornithology and opera, played appealingly by Anthony Giampetro. The hustling team owner is embodied with swagger by Luke Moyer. Finally, there’s a budding literary giant, John O’Hara, a Pottsville native who covered the Maroons for the local newspaper.

The team roster included actors whose faces are relatively unfamiliar and who, therefore, appeared not to be thespians but real Pottsvillians of the 1920s. Among the football players, one notable standout is Chuck Beishl as Tony Latone, a curt, balding, tough older miner who stayed in games even with a broken arm. Beishl in real life has been a roofer for 16 years.

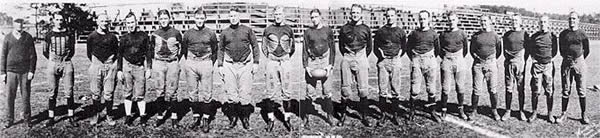

The production includes stunning recreations of football games, with leather helmets and period uniforms. Director Doyle gets the details right — including that era’s wingback formations, pass plays that are impressive on the small stage, and the way the kicker paced backwards from the line of scrimmage.

Coincidences abound. In Molumby’s Million, Saraceni played Jack Dempsey’s manager, Jack Kearns. Now he has written Maroons. Luke Moyer then played Damon Runyon, who was a sportswriter in the early part of his career and who covered Dempsey’s match. Now Moyer is playing John O’Hara, another sportswriter who became a novelist.

Saraceni’s play makes O’Hara its narrator, bringing him more to the fore than Runyon in the previous play. That’s as it should be, because no one defined a town more than O’Hara did with “Gibbsville” (his pseudonym for Pottsville).

At the play’s end, Saraceni wrote a monologue that nails the Maroons’ last-second victory, O’Hara style:

“I’ll tell you every broken down, out-of-work coal cracker in Anthracite raised a glass to those magnificent sons of bitches. They really did it. That was a long time ago. All the fellahs have passed on. And every Schwackie and Mick and Dago that pulled for those boys is gone, too ““- buried down there with the coal and the ash.”

Those are Saraceni’s words, but they sound convincingly like O’Hara.

This article originally appeared in Broad Street Review.