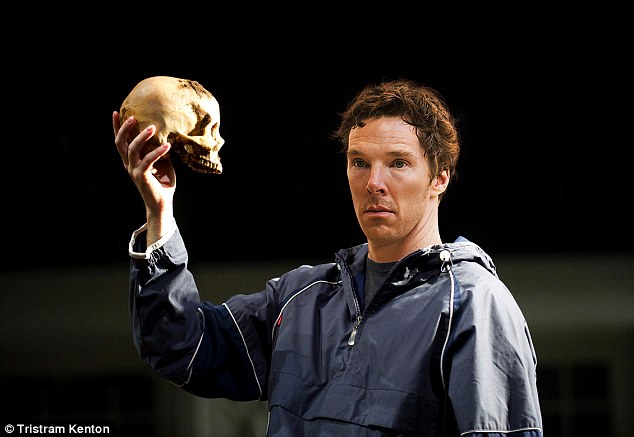

Hamlet by William Shakespeare. National Theatre production at the Barbican, London, 2015.

It’s known as the Cumberbatch Hamlet because the movie star’s appearance in the title role is causing sold-out houses and enthusiastic audience response. But the performance is much more than that.

This is the fastest-moving Hamlet production and the most proactive protagonist ever. Totally gone is the tradition of Hamlet as being indecisive. Normally, he’s portrayed as an intellectual who broods while delaying action. Literature professors went out of their way to rationalize that lethargy by saying Hamlet would have avenged his father’s murder save for the extenuating circumstance of seeing King Claudius in prayer.

Benedict Cumberbatch was expected to fit that intellectualized mold because he rose to fame as Sherlock Holmes on television and then was the cerebral and introverted code-breaker in the film The Imitation Game. Yet his Hamlet is ready to act as soon as he can find an opportunity in this bustling court where people are continually rushing in from the wings and down the staircases.

The constant whirling action is exciting, and Cumberbatch’s acting of insanity is amusing. When he springs into action he’s energetic, and his fencing in the closing scene is athletic. His warmth and agility of mind are palpable. He is a witty and entertaining Hamlet, one with whom we’d like to hang out. You can’t say that about most Hamlets.

The concept’s one flaw is that this king and his entourage do not demonstrate sufficient danger to make Hamlet feign insanity to protect himself from them. His bluffing of madness is insufficiently motivated. Other productions have portrayed the atmosphere of a police state (see more about that, below), while others show the king as an unctuous schemer; this Claudius just seems like a pleasant guy who presides at banquets.

The play needs to show Denmark as a police state. Else we wonder why Claudius became sovereign when young Hamlet was the clear heir to his father’s throne. The only explanation is that Claudius seized power and that he maintains it with enforcers from whom Hamlet must escape.

Director Lindsey Turner’s handing of Hamlet’s monologues is arresting. In the middle of a scene (such as the banquet where he says “O that this too too solid flesh would melt”) Cumberbatch rises and is lit by a spotlight while the other actors freeze. When each monologue finishes, Cumberbatch turns round and action resumes where it left off.

During one of Hamlet’s mad scenes, his impersonation of a toy soldier in a play-school castle is a clever juxtaposition within the castellated prison of Elsinore.

The veteran actor Jim Norton is impressive as Polonius, while Siân Brooke is a properly pathetic Ophelia. Kobna Holdbrook-Smith is a fierce Laertes. Leo Bill is a low-key, sympathetic Horatio. Karl Johnson is a droll Gravedigger who lobs skulls like bowling balls. Ciaran Hinds (of Game of Thrones) is a disappointing Claudius while Anastasia Hille is a pale Gertrude.

This quirky production is mainly, but not entirely, in modern dress. Es Devlin’s set features large chandeliers, portraits and stags heads on the walls. Distant palace rooms are seen in the rear. Strobe lighting and slow motion heighten the drama.

Some of the props are puzzling. Why does Ophelia wield a camera and what’s the significance of the Nat Cole record of “Nature Boy”? Hamlet listens to it in the opening scene and an orchestra repeats the melody in the finale. The point of the 1948 song is “the greatest thing you’ll ever learn is just to love and be loved in return.” A nice sentiment, but I fail to see the connection of that to the story of Hamlet.

Read other reviews on The Cultural Critic