A Human Being Died That Night by Nicholas Wright, based on a book by Pulma Gobodo-Madikizela. EgoPo Classic Theater through November 11, 2018. www.egopo.org/201819festival

It’s extremely timely to watch this play immediately after the synagogue massacre in Pittsburgh. EgoPo’s first homegrown production of the season deals with murders committed by a man who believed that black people should be killed to protect the murderer’s way of life.

The parallel to the gunman who murdered people in a synagogue because they were Jewish is unmistakable.

A Human Being Died That Night is a play by South African playwright Nicholas Wright, based on a book of the same name by a member of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission established by South Africa’s government after the end of apartheid. Steven Wright – no relation – directs it for EgoPo Classic Theater as part of a season dedicated to theater from and about South Africa.

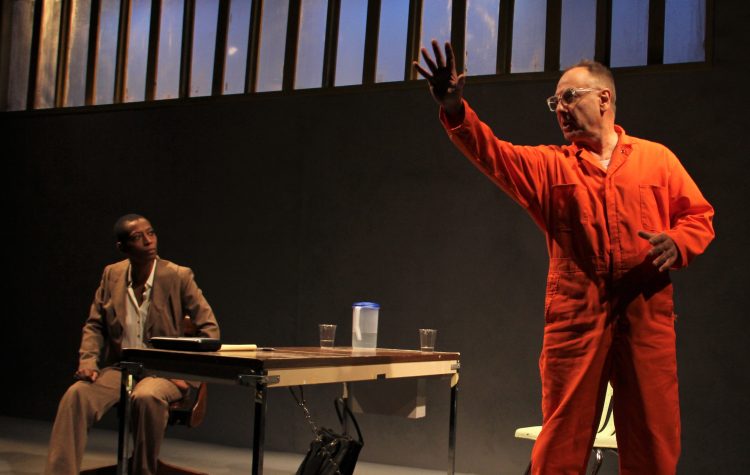

Niya Colbert portrays Pulma, a black psychologist who interviews the incarcerated Eugene de Kock, played by Paul L. Nolan. He is a white police officer who was convicted of murdering hundreds of black people in the early 1990s. She’s seeking his explanation of why he did such horrible things, and he admits his guilt while laying blame on higher-up officials who instigated him and got away with murder.

The set by Yoshi Nomura is extremely simple: grey walls broken only by small, high windows; a table and two chairs. De Kock enters in shackles and he’s bolted to the table. Yet he makes no attempt to escape, nor to be violent. He matter-of-factly details his participation in numerous atrocities. And he informs us that he feared the black people in his nation — just as the Pittsburgh assailant claimed that Jews were supporting immigration of refugees from Central America, and that these immigrants would destroy the United States.

The experienced actor Nolan expresses de Kock’s power and temper, so we understand his ability to commit his crimes. Colbert presents a contrast by using a soft and calm voice. We come away with the impression that people like de Kock play the victim, as if they’re being persecuted, even when they and their representatives hold all the power.

The TRC was established to offer reparation to victims, and to allow perpetrators to express remorse. De Klerk, in this play, doesn’t show much remorse.

An odd occurrence is a mention, late in the play, that blacks in Africa have a problem with AIDS and that Pulma has come back from America because her sister in South Africa was ill. Did the real sister of Pulma have AIDS? I wish that were given more explanation and depth.

EgoPo is providing a welcome exploration of troubling issues, and this production presents them in a gripping manner. Some critics have said that the play’s motif is the principle of forgiveness. I don’t see it that way. As the female narrator/interrogator says, she’s not forgiving, or judging; she’s just laying out the facts. And the playwright intentionally omitted mention that, in 2015, a judge granted de Kock parole. The play leaves that issue up in the air.

Moving past the evil is one thing. Forgiveness is another, and it does not belong on the table. Not for the killings in South Africa, or Charlottesville, or Kentucky, or Pittsburgh.