In 2018 the motion picture industry marks one hundred years since the demise of one of its important pioneering film studios.

Every morning 60,000 cars come racing down Pennsylvania’s route 422, hurtling past Oaks on the way to King of Prussia. They skim over the Schuylkill River, nearing the terminus of 422 where it connects with Routes 202 and 76, the Schuylkill Expressway and the Pennsylvania Turnpike.

How many of the commuters know that every day they are passing the remains of what was the world’s largest movie complex, the Betzwood Studio, founded by movie pioneer Siegmund Lubin?

Lubin was a Polish-German optician (born as Zygmunt Lubszynski in 1851) who invented motion picture cameras and processing equipment and began to shoot movies in Philadelphia in 1898. Lubin opened movie theaters in twenty cities and shipped his films to exhibitors around the world. Lubin has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame because of his contributions to the industry.

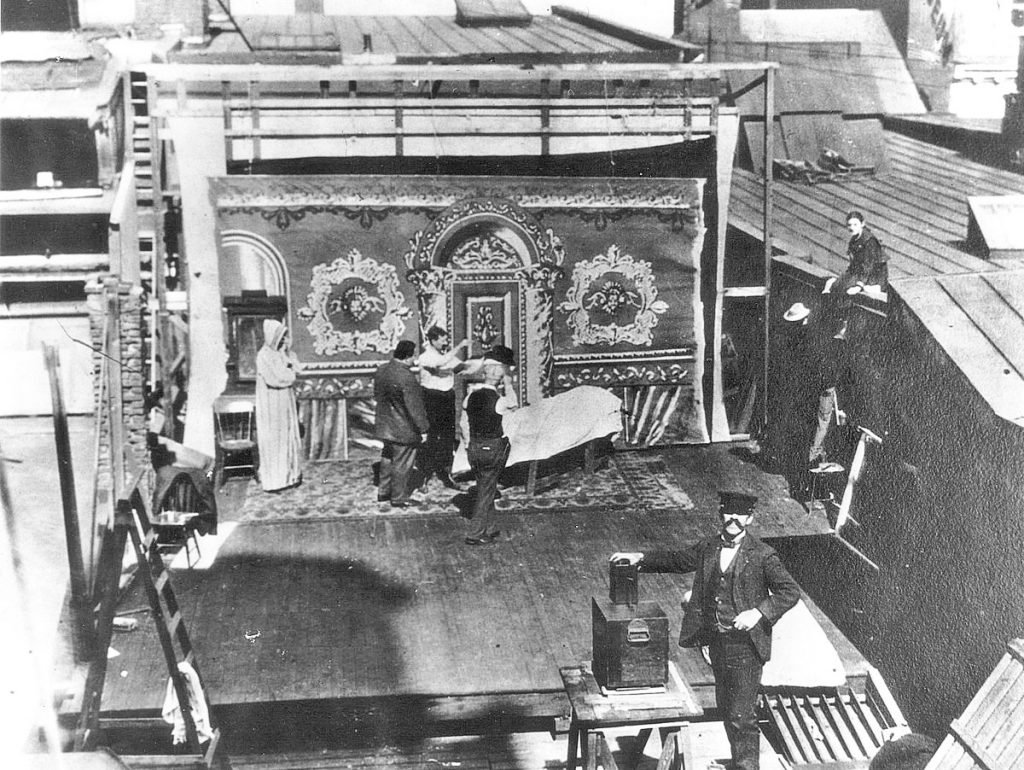

D. W. Griffith filmed the first movie ever shot in Hollywood in 1910, but studios were not built there until 1913, long after Lubin had established himself in the Philadelphia area. His first studio was on the rooftop of 912 Arch Street, then, in 1910, at 20th & Indiana Streets. His logo was the Liberty Bell and his slogan “clear as a bell” touted his films’ sharp focus.

In 1912 Lubin bought the Montgomery County estate of brewer John Betz and began to develop Betzwood. His campus covered 350 acres and included two enclosed dark studios, a glass studio, processing plants, stables, farms, woods, a train station and, of course, the Schuylkill river. All of this gave Lubin the ability to shoot feature-length Westerns and Civil War epics.

Betzwood employed 700 people, including costume makers, film developers, technical staff, publicity staff, shippers, kitchen and dining room help. The studio was air conditioned and humidity controlled.

Lubin’s The Servant Girl’s Legacy in 1914 was the earliest surviving film of Oliver Hardy. Director Arthur Hotaling needed a “fat boy” and Hardy, who hung around the studio in hopes of getting a break, was the heaviest boy available.

But most of Lubin’s films were demolished by a fire and Lubin’s business was destroyed by bankruptcy, and Betzwood’s history became almost forgotten. There is not even a marker to tell the passerby anything about the studio.

Joseph Eckhardt is a film historian on the faculty of Montgomery County Community College who founded the Betzwood Film Festival. Because of Eckhardt’s prodding, the City of Philadelphia designated the site of Lubin’s optical shop at 21 S. Eighth Street a historic shrine. The County of Montgomery has so far done nothing similar at Lubin’s studio. It’s much more important than the optical shop, and much of it is preserved.

Eckhardt picked me up one morning to take me on a tour and show me what remains of Betzwood.

You get there by looping off of 422 at the Trooper Road exit, and hanging a left. As you drive underneath the highway you come to a parking area with wooden tables and chairs. The former Pennsylvania Railroad tracks that connected Betzwood to Philadelphia are now a biking path. Joe and I walk along it, noticing the wild grapes, blackberries, strawberries and honeysuckle at its edge. “The air used to smell so good at Betzwood,” said the late Blanche Wolf Kohn. “And the food tasted so good. We grew it ourselves.”

Lubin, it turns out, was a bit of a socialist. Unlike most of the Hollywood studio heads who were conservative capitalists, Lubin provided free hot meals and free medical and dental care to his employees. He wanted to make Betzwood a self-sufficient commune with its own school, farm and hospital. Many aspects of Betzwood were synergistic. For instance, his workers grew grain to feed the horses and also to make bread for the people. Lubin imported cattle for his Western scenes, and also to provide milk for his free lunches.

Joe and I walk for a mile or so, parallel to the river, past buildings that contained scenery on the second floor and stables on the ground floor. We see the loading docks for the railroad right off the bike path. We pass the spot where once there was a massive Edwardian boathouse and the building where the cowboys lived.

Joe and I walk for a mile or so, parallel to the river, past buildings that contained scenery on the second floor and stables on the ground floor. We see the loading docks for the railroad right off the bike path. We pass the spot where once there was a massive Edwardian boathouse and the building where the cowboys lived.

Still visible are two small square buildings that once were used for film storage. In the field nearby, Lubin built a “desert” with fake cactus plants and real jackrabbits imported from Arizona. Just north of that was the Western set, consisting of two streets with saloons, a general store and a sheriff’s office. Once Lubin built a town of 40 structures and then burned it down for a scene in one of his films.

John Norris of Phoenixville remembered his mother taking him to Philadelphia for a doctor’s appointment in 1915. As the commuter train stopped at Betzwood Station it was ferociously attacked by a horde of Indians, and then Norris and his mom were rescued by the U.S. cavalry. Later he learned that the “Indians” were actors, and he had accidentally become part of a Lubin motion picture.

Civil War battles were staged in the area that is now Valley Forge National Park. There was a Victorian mansion which was torn down in 1962 to make way for St. Teresa of Avila parochial school. And a teahouse stood along the trail that is now Route 363. Ida Breuninger, at 96, remembered lunching there with actress Marie Dressler. Ida was 18 and worked in the film-editing room. She later married the founder of the Breuninger Dairy.

Lubin was the first Jew in the film business. Adolph Zukor and Samuel Goldwyn started a few years after Lubin, and Louis B. Mayer even later, in 1918. A small number of Lubin’s films reflected his own ethnicity. In the Land of Suppression (also known as The Hebrew Fugitive) Lubin showed Jews in Russia being harassed by Cossacks and eventually fleeing to America. Another was called The Yiddisher Boy and a final one was Breaking Home Ties.

Also shot at Betzwood were a series of two-reel shorts based on the Toonerville Trolley cartoon strip. Some of the narrow-guage trolley tracks are still visible.

So great was Lubin’s fame in 1914 that he was the guest of honor at an industry banquet in New York City. Movie moguls Adolph Zukor, Sam Goldwyn and Jesse Lasky were in the audience and paid tribute to Lubin. They laughed and applauded as Lubin spoke for 45 minutes about the past and the future of the film industry.

All of them — and Cecil B. deMille also — came to Lubin for help in making their first films.

But, at the zenith of his prestige, Lubin was about to fall. The causes of his collapse were several:

1. European markets were suddenly closed to him by the World War;

2. An explosion and fire at his Philadelphia studio destroyed the negatives of most of his films;

3. Lubin had borrowed so much money to build Betzwood that he owed the Drexel Bank half a million dollars. In 1918 the bank foreclosed on Betzwood and forced Lubin into bankruptcy.

Deeply depressed, Lubin retired from the movie business and died in Ventnor, NJ, in 1923.

Joe Eckhardt moved to this area in 1962 to teach history at Montco. A few months later he saw a newspaper story about the tearing down of Betz’s mansion. That got him started. He researched the history of Betz, and then of Betzwood. Film buffs are now rediscovering Lubin and Betzwood and reminding us that Philadelphia’s Main Line was once, briefly, the film capital of the world.

Photos are from the Portus Acheson collection at Montgomery County Community College

Below, Lubin’s Philadelphia rooftop studio in 1899: