And Tell Sad Stories of the Deaths of Queens, by Tennessee Williams; directed by Lane Savadove, September 2019 at the Philadelphia Fringe Festival.

The surprise hit of the 2019 Philadelphia Fringe Festival is this rare Tennessee Williams production.

It’s no surprise when EgoPo Classic Theater and its artistic director, Lane Savadove, do fine work. But it is amazing to find that this virtually-unknown 50-minute play can be so emotionally satisfying. This is due especially to the touching performance of Rob Tucker as the central character of a New Orleans drag queen.

He’s impressed us in numerous musical and dramatic roles in the past. Most relatable was his interpretation of the “Nice” Nurse in A New Brain for 11th Hour Theatre and for Theatre Horizon, who sang that he was “unsuccessful, and fat, and getting older.” In this play, he is dreading his 35th birthday, and bemoans the fact that his male lover for 17 years left for a younger man. Tucker is warm, inviting, self-deprecating.

When performed this well, And Tell Sad Stories of the Deaths of Queens is not a lesser work; it’s simply an unjustly neglected play about desire and self-delusion.

Williams derived his title from the final speech of Shakespeare’s Richard II: “Write sorrow on the bosom of the earth…and tell sad stories of the death of kings.” Like King Richard, this main character gives up money and safety to try for a personal connection.

The play was written in 1957 at the height of Williams’s fame, but never staged during his lifetime and not published til long after his death. At its center is a male who is a fading southern belle — trademark Tennessee Williams — adrift in a world that doesn’t accept her.

Williams was accused of creating female leading characters that were stand-ins for gay men. But, he replied, “if I wanted to write a play about queens, I would have.” One doubts his accuracy, because this was the buttoned-up 1950s. And our doubts are confirmed by the fact that Williams abandoned the play.

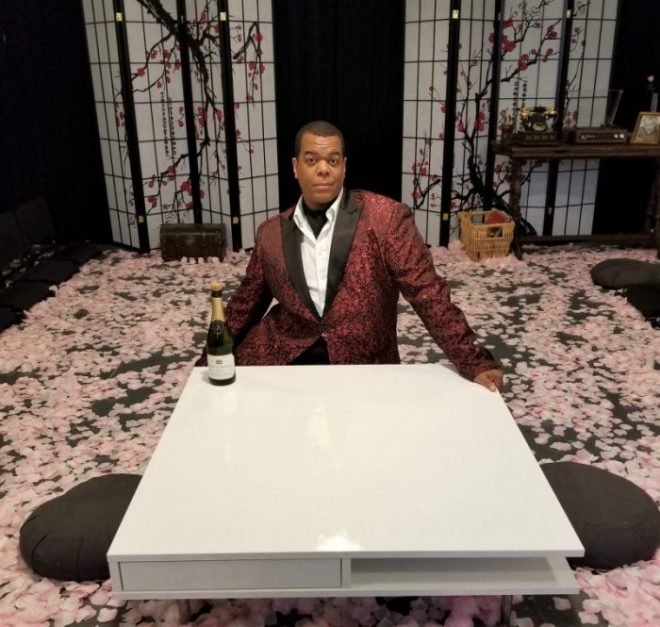

Not only are most of these characters overtly gay, but they are queens and Candy is a part-time transvestite. “She” is an interior decorator and property owner in New Orleans’ French Quarter who rents out two other properties and the upstairs of “her” home to extroverted gay boys. Tucker plays Candy with a natural effeminacy, without exaggeration or caricature. When she changes into a gown, her manners and her speech become even more soft and womanly.

Williams intentionally gave the play Japanese overtones which are realized beautifully in this production.

And Tell Sad Stories of the Deaths of Queens parallels Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly which is about a geisha pining for a man who will never love her in return. The opening scene, according to Williams’s script, includes a mechanical piano which is playing “Poor Butterfly,” a 1915 pop song inspired by Madama Butterfly and containing (in its verse) a musical quote from the opera.

“Poor butterfly

‘Neath the blossoms waiting

Poor butterfly

For she loved him so…”

Savadove’s production has Candy play a phonograph record of that song. It also presents a lovely adjoining garden of Japanese design, which we cross on our way to be seated, with a fish-pool, a flagstone path amongst flower petals, and an arched bridge with paper lanterns. Candy’s parlor has a low Japanese table and Japanese furnishings.

Candy goes to a queer bar and brings home “a big young merchant seaman,” Karl, serves him strong drinks and hands him money. Candy offers Karl her place at his disposal and unlimited credit at every bar in the Quarter, plus more cash.

Candy says she’s lonely and just wants friendship, but seems to be trying to fool Karl, and maybe herself. She delusionally believes that a real relationship exists. The dialogue careens between taut and tender and humorous.

Although she seems self-confident at the start [see photo above], Candy gradually reveals self-loathing. Eventually she displays hatred of the tenants, derisively calling them queens, and then bitches. Expecting an early death because of a congenital heart “leakage,” she is courting self-destruction.

As Karl, Nick Ware is tall, as the script requires, but not as physically imposing and menacing as we’d like. His character reminds us of Stanley Kowalski and should present a threat as ominous as that of Stanley’s to Blanche DuBois. Ware was properly boorish and made clear his interest in heavy drinking and money. He also divulged that, when drunk, he can be violent.

Kerry Jules and Charlie Barney were vivid as the tenants. Dane Eissler designed the gorgeous production and Curt Foy choreographed the sudden action in the play’s final moments, which I won’t disclose.

EgoPo is sharing the production with Provincetown’s Tennessee Williams Theater Festival, September 26 through 29, 2019, in Massachusetts.

To hear about a previous EgoPo production of another Tennessee Williams play set in New Orleans, read on:

Vieux Carré by Tennessee Williams, directed by Lane Savadove, December 2007. Originally published in Broad Street Review in 2007.

by Steve Cohen.

The works of Tennessee Williams, his words dripping with desperation, have been absent of late in theaters. And his Vieux Carré never received many performances even when Williams was popular. How audacious, then, for EgoPo to schedule a Williams Festival and to open it with this 1977 play.

On the other hand, how natural a choice it is for EgoPo, which developed in New Orleans and relocated in Philadelphia after Hurricane Katrina destroyed its home, sets and costumes. Williams wrote about New Orleans and this play is set in, and named for, a New Orleans neighborhood.

Lane Savadove lived and worked in New Orleans for four years and directed Williams’s plays there. So it’s a logical pairing but not a slam dunk, because the genre has faded in popularity. Therefore I’m pleased to see how well Savadove and his company have succeeded.

Under his direction, Vieux Carré comes across as a sequel to The Glass Menagerie, displaying the playwright’s maturation after he left his mother and sister in St. Louis. Moving into a decaying rooming house in the Vieux Carré district, the young Tennessee — here called The Writer — lives among drug addicts, thieves, alcoholics, tuberculars and gay people as he explores his own sexuality and begins to write on an Underwood portable typewriter.

The play makes a nice distinction between the Writer as a young man and as a mature man returning to reminisce and narrate. The young Writer speaks unaffectedly, with an accent typical of his St. Louis upbringing, while the older man speaks with the acquired panache of a Southerner. Williams lived the first seven years of his life in Mississippi and he had family in Tennessee, so perhaps he came by a Southern drawl naturally. But the evidence suggests that he put on his exaggerated, effete New Orleans accent as an affectation.

The play introduces us to an eccentric landlady and her tenants, who include a flamboyantly gay artist, a society girl on the run, an abusive lover who has moved in with her, and two lady roommates who pick the trash to avoid starving to death. Through the combination of Williams’s skill as a storyteller, Savadove’s direction and fine acting, we get to care about these uniformly lonely residents. “There’s so much loneliness in this house you can hear it,” says the Writer as the stage band plays Duke Ellington’s “Solitude.”

Each of the characters turns out to possess interesting dimensions, revealed in degrees as the evening progresses. Particularly haunting is the artist who is ill with tuberculosis and denies his sickness, much the way Roy Cohn does in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America. This man claims to have a cold, then says he was treated in the hospital for “asthma.” In one of the play’s most gripping moments, the Writer tells the dying artist to stop pretending and admit what he has. Williams seems to be telling himself to come out and be what he is. Savadove stages this most intimate moment by having the two actors pick up microphones and whisper their words through an echoing amplification system.

Savadove takes the three-story dwelling and stages it horizontally, on one level of a deep stage as if we’re looking at a floor plan. In his conception some of the action thrusts forward while other action recedes to the rear. Savadove’s approach also stresses physicality and intense emotion. That makes this old play jump out at us.

Excellent performances are turned in by Doug Greene as the Writer, Leah Walton as the landlady, DaVine Randolph as the housekeeper, Andrew Borthwick-Leslie as the artist, Megan Hoke as the society gal and Nathan Edmonson as her lover, plus Sarah Schol, Kristen Schier, Eric Snell and Robert DaPonte.