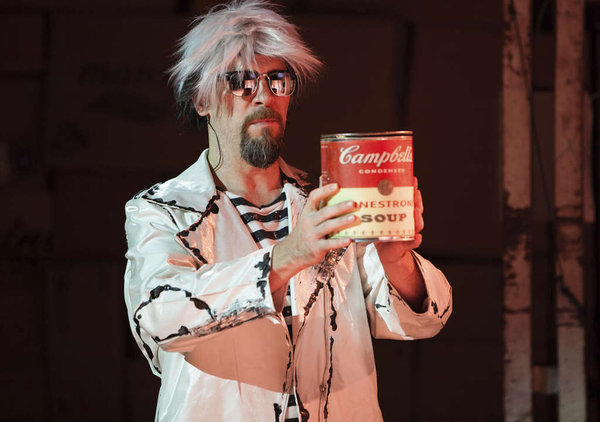

Andy a Popera, world premiere by Opera Philadelphia and Bearded Ladies Cabaret, 2015

This is a production that Andy Warhol could have designed himself. It’s his sort of flamboyant imagery, presenting odd characters in outrageous costumes. In some ways, it’s even better as it adds dramatic narrative that Warhol’s paintings do not attempt.

But is it an opera? The producers deflected that question by specifically labelling it as Popera.

I enjoyed myself but must report that some regular opera patrons fled at intermission. Others stayed, but grumbled “This isn’t where we want our money going.” (It must be noted that this was not part of the regular subscription season, and the purchase of Andy tickets was optional.)

Some of the objections were because of intentionally grungy presentation techniques employed by the opera company and its producing partner, a cabaret group called Bearded Ladies. Instead of using a center city theater, they chose a warehouse in the Kensington neighborhood in homage to Warhol’s Manhattan studio which was a large warehouse he called The Factory.

Also, after presenting a ticket, attendees hands were rubber-stamped. This was not needed to keep free-loaders from sneaking in; after all, this was not Times Square but, rather, a lonely part of the city. The procedure seemed to be a calculated attempt to suggest a rock-concert experience.

The score credited to Heath Allen and Dan Visconti was an eclectic assemblage, mixing Middle European melodies (Andy’s family was Slovakian), pop songs, snatches of opera (from Carmen and Rigoletto), psychedelic haze and soft rock. Some listeners found it unfocused, yet in its best moments it added emotion to the story.

Andrei Warhola (1928-1987) was an ad illustrator and a decorator of store windows who became the most prominent leader of the 1960s Pop art movement. Andy spotlights Warhol’s penchant for turning commercial labels and ads into works of art, especially through multiple repetitions of the images. Arguments continue in the art world as to whether his repetitions reveal deep meaning or are mere entertainment.

The first act engrossingly revealed Warhol’s background and his development into an artist. Andy emerged from a box within a box, reminding us how he often used that image. Then he morphed into four replicas of himself. His Campbell soup cans and his Marilyn Monroe posters also figured in the early scenes, triggering colorful ensemble numbers. We saw eight different Marilyns, one of them being a bearded man in a crazy rainbow of wigs.

Video projections by Jorge Cousineau captured Warhol’s intentionally-haphazard film technique and his desire to turn the observer into a component of his art, to draw us all into active participation.

We learned of Warhol’s credo that “Art is anything you can get away with.” Even more importantly, we heard Warhol say “Don’t expect to live forever; create something that will!”

Mary Tuomanen was a near-perfect Andy. Her boyish figure and straight blonde hair captured Warhol’s look. Already known for impressive acting on legit stages, she here revealed a fine singing voice.

The coordination of forces was impressive. A live band was to the side of the stage while a dozen performers fanned out in all directions, mixing with audience members and popping up on raised platforms far from the main playing area but staying in synchronization. Some pre-recorded high notes were smoothly added to the live vocals by the performers.

The first act ended with the shooting of Warhol by one of his followers, Valerie Solanis (Kate Raines). This is a logical intermission point, yet it left the Popera with a weak second act in which the title character barely appeared. As he lay in a coma, a group of songs was devoted to the woman who shot him. The work regained focus to conclude with a choral paean to Warhol and re-appearances by a group of individuals who received their “fifteen minutes of fame” through Warhol.

Malgorzata Kasprzycka made a robust impression as Andy’s immigrant mother, with a wide-ranging closing aria. Many of the minor characters also had legitimate operatic voices, coming from the ranks of the Opera Philadelphia Chorus.

Before this work is produced elsewhere, the creators should consider making it a continuous one-act piece. Puccini, after all, improved his Madama Butterfly by turning the second and third acts into one act.

Forty per cent of ticket buyers for the production had never bought Opera Philadelphia tickets before, according to the company. The question remains: How many of them will return for any main-stream operas? Conversely, how many regular subscribers were so offended that they will shun further excursions into unusual territory? How many will increase their financial contributions and how many will cut them back?

Please share your thoughts and your opinions with us. Address to editor@theculturalcritic.com

Read other reviews on The Cultural Critic