The Diary of Anne Frank. Lane Savadove directed. EgoPo Classic Theater, 2011

The diary, the play and the movie are so familiar that you wonder if you need to see it again. Be advised: This Diary of Anne Frank is different from what you grew up with. It’s better, too. Among other things, it’s less squeamish about Anne’s adolescent awkwardness and her family’s Jewishness.

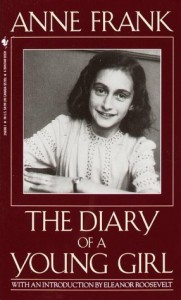

This EgoPo production uses an adaptation by Wendy Kesselman of the play that Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett fashioned from Anne’s wartime diary in 1955. The original version was sanitized to soften some gritty words and to make Anne seem more “universal” and less specifically Jewish. Recent years have seen unexpurgated editions of the diary as well as this new script in 1997.

Three major differences from the original stand out. The 13-year-old Anne is more outspoken in her hostility towards her mother, voicing a friction that’s normal for her age and, later, a yearning for a closer relationship. Anne and the others trapped in the hidden Amsterdam hideaway are also angry with the Queen of the Netherlands for surrendering so quickly to Hitler, and with the British for what they perceive as their unnecessary tardiness in launching a cross-channel invasion to liberate them.

In the play’s second act, when Anne is turning 15, she talks about her periods, her interest in her body and in the beauty of other women’s bodies. Just as you begin to wonder whether she has gay tendencies, Anne reveals her longing for Peter, the young son of Anne’s father’s business partner who is living in the same attic. The development of this romance is more believable and engaging than in any previous productions I’ve seen.

Finally, this script contains many more references to the particularity of Jews, in contrast to the old version, which submerged everyone’s Jewishness in universal generalities. The Franks actually weren’t observant Jews, and only one man among the four ever puts on a head covering for prayer. But all of them know the Hanukkah blessings by heart and recite them spontaneously. They take turns lighting the menorah candles and in singing the traditional “Ma’oz Tzur.” Their joy in their shared culture is palpable.

The occupants of the hiding place also express bitterness because the Allies aren’t bombing the German trains carrying Jews eastward to death camps. Anne wrote this in 1943. So much for those who said that no one knew what was going on.

It’s important to keep in mind that The Diary of Anne Frank is Anne Frank’s own story, not some outside observer’s. Anne was a 13-year-old with a creative bent who might have grown into a successful writer. Her expression is inconsistent as her normal changes of adolescence are exacerbated by her lack of privacy and her dangerous surroundings.

Her words ring so true that I forgive her less-than-polished verbiage. Anne succeeded in creating a subjective story that told in microcosm what could barely be comprehended when people tried to examine the vastness of the Holocaust.

The direction by Lane Savadove emphasizes the clashes between the desperate people trapped together. Never have I felt as much tension caused by their claustrophobia— never able to go outdoors or open a window or even raise a shade. The intimacy of the Prince Theater’s upstairs performing space causes audience members to feel we’re sharing this cramped room with the family.

Savadove’s cast is well chosen and each of them presents an individual personality. Rob Kahn is an excellent Otto Frank, Anne’s father, as are Melanie Julian as her mother and K. O. Delmarcelle as Anne’s sister Margot. Brendan Norton is the maladroit dentist Dussel; Russ Widdall is the blundering but eventually endearing business partner Van Daan; and Mary Lee Bednarek is Van Daan’s out-of-her-element wife.

The Anne, Sara Yoko Howard, is a recent college grad who looks younger and whose motion and expression convince us that she’s only 13. She is precociously effervescent, with a daring spirit that allows her to view this captivity as a great adventure. Her gradual maturing into a relatively sophisticated 15-year-old is a considerable acting feat.

Matching her is Johnny Smith as Peter. He, too, is not nearly as young as the boy he portrays, showing how well he uses his talents.

Two elements that were beyond the creative powers of Anne the author, or of any playwright, turn this story into haunting tragedy. First, the Allied invasion of Europe in June 1944 brought delirious joy to the attic for the first time in more than two years. Anne remarks how lucky she is to have survived while most of her school friends are probably dead— and right after that the Nazis burst into the attic.

Second, the sparkling and resilient Anne became drained of spirit in a concentration camp and then died a few weeks before the war ended. Anne’s father was the only survivor; in the play’s epilogue, he finds the diary. That was all that was left. Plus, in this production, a music box that played “Ma’oz Tzur.”

Please share your thoughts and your opinions with us. Address to editor@theculturalcritic.com

Read other reviews on The Cultural Critic