With the escalating cost of productions, workshops have become the dominant way of testing new theater shows. They are private affairs, attended only by the participants until the very last day. Then a final run-through is performed in front of a small group of invited guests — investors, producers, agents, friends of the participants. Reporters and reviewers normally are not invited.

We had a rare opportunity to sit in on a theater workshop. The rules were broken with a musical called Baby Case in development at the Arden Theatre in Philadelphia. Even if you don’t care about this particular play, you might enjoy this revelation of the process.

Baby Case is about the hype that surrounded the 1932 kidnaping of Charles Lindbergh’s baby and the trial and execution of Bruno Richard Hauptmann for the crime. Terrence J. Nolen, the Arden’s artistic director, allowed us to sit in from the first meeting in June of 2000, during two weeks of work, a public script-in-hand performance, and another two-week workshop with expanded forces in June of 2001. The work received its world premiere in October of 2001 at the Arden. Michael Ogborn wrote the book, music and lyrics, and he welcomed this access to his creation.

Baby Case had an earlier reading — “readings” are abbreviated workshops — in the basement of St. Peter’s Church in Manhattan in November, 1998. According to the rules of Artists Equity, a reading is limited to 20 hours of work. A workshop, in contrast, can run for two weeks of eight-hour days. After the 1998 reading, Ogborn received advice from his playwright friend Christopher Durang and others, and made changes and additions in preparation for the more intensive 2000 workshop.

Here, now, is a chronicle of Baby Case. This journal provides many small details to provide a sense of what it’s like to be in the midst of the process:

The First Workshop

June 12, 2000. On a hot and humid Monday morning, with thermometers in the 90s, performers climb two flights of steps to the rehearsal studio at the Arden Theatre Company, located on 2nd Street above Market Street in Philadelphia, across an alley from historic Christ Church. The studio is a high-ceilinged room with exposed water pipes and air ducts. Most of the participants are in T-shirts, shorts and sandals.

There are two noticeable exceptions. Vince DiMura wears a long-sleeve purple shirt, psychedelic vest, black pants and shoes. His dark brown hair is pulled into a braid that falls almost to his waist. “You can always tell the musician,” observes Terry Nolen, who is directing the project. Nolen himself looks more yuppie than theatre, with his buttoned, long-sleeve striped shirt hanging loose over khaki pants. He has a trim sandy-brown beard and roundish wire-rim glasses.

DiMura is, indeed, a musician. A New Jerseyan, he teaches at Temple University and is pianist and coach for Broadway performers. He is music director for this workshop, which means he’ll be in charge during the first few days, while Nolen listens and gets to know the play better. After that, Nolen will give direction while DiMura continues to conduct the music.

Nolen greets the seventeen singer-actors around a long, rectangular table. His stage manager, Patricia Sabato, passes out scripts, music scores, Equity contracts and W-4 forms — routine paper work that must be completed before the artistic work begins. This is the first time the actors are seeing the script and music.

Nolen asks all to call out their names and some identification. “I’m Debbi and I’m a soprano,” “I’m Scott and I’m a tenor,” is the way it starts. “I’m Ben Dibble and I’ve been asked to read the part of Lindbergh,” says a young man with red hair and blue eyes. His hair has been dyed that color for the role of Jack, the beanstalk climber, in the Arden’s current production of Into the Woods. Richard Ruiz, a young man with dark complexion and black curly hair, gets a laugh when he introduces himself by saying: “I think I’ll be playing the Mexican.”

When a tall, slender guy with short brown hair says “I’m Michael Ogborn and I’m the author” he gets a round of applause. Most of the actors have never seen him before, though Ogborn has accumulated an impressive reputation for writing musicals such as the AIDS-awareness C’est la Guerre and Regalia: A Gay 90’s Review. Age 39, he is a Philadelphia native who moved to New York City in the early 1990’s. His satiric comedy with songs, Box Office of the Damned, was performed at the West Bank Café in Manhattan and by other theater companies.

Ogborn describes Baby Case in a note attached to the script: “Quick-edit techniques should create a feeling of channel-surfing through the crime of the century as if it’s 2000 and the Lindbergh Baby has just been kidnaped and the story is on every channel.” In conversation, he expands on that: “The play explores the nation’s fascination with every detail of the case, regardless of how bizarre or unfounded. It satirizes the personalities that rose and descended in the media circus and court proceedings. There’s definitely a tabloid quality to it. The idea that the world descended on this tiny little hamlet where the trial took place — that’s what got me. That the reverberations could come from such a tiny, early 19th-century town.”

The show starts with the song “American Hero” about the adulation of Lindbergh that got out of hand, overheated by the American press led by Walter Winchell, the columnist and broadcaster. Charles Lindbergh had been Time magazine’s first Man of the Year, described as “6 foot 2 inches, age 25, cheeks pink; characteristics Modesty, taciturnity, singleness of purpose.” Nolen says that he sees Baby Case as a combination of Busby Berkeley and Bertholt Brecht. How so? “It’s definitely of a period, the 1930s, when Berkeley and Brecht were dominant figures. The show will have moving platforms, flying pieces, black-and-white newsreel projections and ensemble numbers with brightly-colored costumes to remind us of Berkeley.” And what’s Brechtian? “The presentational approach. The characters address the audience more than they address each other. And the fact that the story is told partly with newsreels and headlines.”

While the actors are putting their names, addresses and signatures on the contracts — which call for a modest $487 a week — Sabato informs them of the schedule: 10 til 6, six days a week for two weeks, with one hour off for lunch each day. Nolen then tells the group the background of his company. He says the Arden’s been doing musicals every year since it was founded by him and Aaron Posner in 1988, shortly after they graduated Northwestern University. “But this is will be our first musical world premiere. Musicals are much more expensive than straight plays because we hire musicians, a musical director, choreographer and so on. And we’re not like large New York theaters that can earn the money back by selling lots of tickets. We have only 350 seats and we have limited runs. So producing a musical is a big and expensive risk. That’s why we decided we need a workshop.”

DiMura asks everyone to pull their chairs in a semi-circle around his upright piano. Many of the cast carry water bottles with them. A few also bring small cassette recorders. Some of them can not sight-read music. They look at the score to read the lyrics and to get an idea of when notes go up and when they go down, but they learn the songs mainly by repetition. They’ll be practicing at home while playing back the tapes that they make during the work sessions.

You might think that Broadway actors are more “professional” and don’t work this way. But one of the best-known of all Broadway conductors, Paul Gemignani, tells me that this is typical: “Even in New York, most actors don’t sight read. I have to teach them the songs by rote.”

We quickly learn the importance of the musical director during a workshop. DiMura starts on the most elemental note by leading the group in simple scales. Then he develops harmonies: “Basses stay on that note. Tenors go up. Sopranos down a half. There, that’s a nice chord.” In the first song, he teaches the beat by having the cast recite the lyrics in rhythm while he claps his hands. He calls attention to the length of the rests that are written. “A rest isn’t nothing. It’s a something and it has to be performed.”

The script shows contrasting sides of Lindbergh: his heroism, his arrogance and his flirtation with Nazism. And the play focuses on babies. The Lindberghs had another son between the death of their first and the start of the trial, and the Hauptmanns also had a baby. At that moment, from the back of the room, comes an infant’s cry. Nolen’s wife (and Arden executive) Amy Murphy is feeding a bottle to their five-month-old son, Liam. She tells everyone that Liam loves show music, “but, still, we’re going to make sure that he’ll be a doctor!”

DiMura has a six-year-old and also thinks a lot about youngsters. He tells the cast that a certain passage has to be sung softly. “”You know how, when you have a baby and he falls asleep, everyone has to talk softly because you don’t want to wake him.” Well, actually, the actors don’t all know that. It turns out that only one member of the cast has a child. A singer named Chrissy says that her mother is looking after her nine-month-old. But, at other workshops, there are many mothers who have to hire baby-sitters. One New York singer told me that she runs a deficit whenever she’s in a workshop, because babysitters cost more than the wages she makes. So why do she — and the others — want to do a workshop? It’s the adventure of being part of the making of a new work of art.

Scott Greer is performing a lead role in Into the Woods while he’s workshopping Baby Case. So he’s singing  Ogborn every day and Sondheim every night. Why does he take on the double schedule? “It’s a paranoid actor’s instinct. You take any work you can, because you don’t know when you’ll get your next job. And, also, Ogborn’s stuff is interesting.”

Ogborn every day and Sondheim every night. Why does he take on the double schedule? “It’s a paranoid actor’s instinct. You take any work you can, because you don’t know when you’ll get your next job. And, also, Ogborn’s stuff is interesting.”

DiMura and Nolen ask the tenors in the group to take turns trying a song for Hauptmann. “No, I Never Did” is a waltz that ends with a ringing high G. Ruiz stands and sings with his score in his right hand and his Panasonic recorder in his left. Nolen is looking for a Hauptmann who can hit the notes and also be sympathetic, because he wants the character to engage the audience as much as Lindbergh does. He listens to everyone twice but won’t make a decision til later in the week. Parts will have to be assigned, changes made and new things have to be written.

Tuesday, June 13. Ogborn explains why the script contains only a sketchy ending for Act One, including a reprise of the title song. He wants to compose a new ballad for Mrs. Lindbergh for that scene. Meanwhile, today will be devoted to learning other songs. All the men try a satirical number by a man who photographs the dead body of the baby, “If I Could Take a Picture of You.” The show includes a scene, which is factual, where vendors hawk autopsy photos of the dead baby to the crowds that gather for the trial. In contrast to the subject matter, the song is in the cheerful key of C-major at a rollicking 6/8 tempo. “Think of Irving Berlin and Fred Astaire,” DiMura advises. Cast members are tapping their feet and snapping their fingers as they sing. The next time you find yourself tapping your feet at a musical, don’t feel guilty. The professionals do it too, at least in rehearsals.

DiMura instructs a singer to hit a note with greater impact: “I’m Italian. If I want to stab a guy I want to drive his heart right through his back. That’s how I want you to attack that note.” In an aside, he says: “You use imagery on actors and they get it.” It’s clear that the music director occupies a more important role than the public realizes. No wonder that the musicians union has been pushing to have a Tony Award given in that category, something that’s not now done.

Late in the day, Ogborn sits alone with Mary Kate McGrath, the woman portraying Anne Lindbergh, and plays some ideas of his. He wants her input as to what feels right for her voice. He also asks her to sing so he can carry her sound in his head when he composes her big song.

Wednesday, June 14. While songs continue to be rehearsed, smaller characters are being assigned. They include reporters, photographers and radio announcers. Some lines written for a reporter named Jamieson are now reassigned to Walter Winchell, who originally had a smaller part. Why? Jamieson won a Pulitzer for his coverage of the trial, but Winchell’s name is better known. Winchell will now open both acts and frame the action as he delivers newscasts.

The Act One finale isn’t done yet. Ogborn explains why he’s anxious about it: “This is the most important number. It has to be good enough to make the audience come back after intermission.” While DiMura coaches singers at the piano all day, Ogborn and Nolen talk about how scenes can be staged when Baby Case eventually is presented with sets and costumes. That’s assuming the workshop goes well and the Arden schedules the play for a full production.

Thursday, June 15. Ogborn pulls his chair up to the piano, sits on the treble side of DiMura and plays a few chords. He and Vince try a problematic section several different ways. Then Vince pencils in the change: “Bottom notes of the chord an octave lower than what’s written.” In the middle of rehearsing one song, Nolen interrupts and asks DiMura to try taking it down a key. Does the composer mind? “No,” he says. “I’m mainly a playwright and interested in the text. I’m not married to the notes.”

Nolen assigns all the parts and gives instruction on German dialect to actors who will play German immigrants. While DiMura keeps rehearsing the cast, Ogborn sits across the room, biting his nails, reading Anne Lindbergh’s diary, looking for ideas for that Act One finale. “I’m trying to learn Anne’s voice,” he says. Later, Ogborn sits alone at the piano and sings one of his songs for Mrs. Lindbergh, “A Mother’s Son,” in a soulful falsetto. Everyone is riveted.

Friday, June 16. The first run-through of all the dialogue and music, in order. Now the cast is in a big circle.  DiMura has moved from the piano to be part of the circle, while Ogborn and copyist Lona Kozik take turns at the keyboard. When he gets excited, DiMura moves into the center of the circle, crouching and pointing cues. But Ogborn still hasn’t finished Act One. Stage manager Pat Sabato puts yellow stick-ems on the script: “Remind Scott it’s pronounced LAY-zay-fayr,” for example. She also uses a sports watch to clock the running time. Nolen and Ogborn are ditching things that don’t seem to be working. When Michael feels that something isn’t right, he glances over at Terry and wonders what his reaction is. “Often,” says Ogborn, “he’ll look back at me and I know instantly that we agree.”

DiMura has moved from the piano to be part of the circle, while Ogborn and copyist Lona Kozik take turns at the keyboard. When he gets excited, DiMura moves into the center of the circle, crouching and pointing cues. But Ogborn still hasn’t finished Act One. Stage manager Pat Sabato puts yellow stick-ems on the script: “Remind Scott it’s pronounced LAY-zay-fayr,” for example. She also uses a sports watch to clock the running time. Nolen and Ogborn are ditching things that don’t seem to be working. When Michael feels that something isn’t right, he glances over at Terry and wonders what his reaction is. “Often,” says Ogborn, “he’ll look back at me and I know instantly that we agree.”

At the end of the run-through, Nolen says that there’s one word that isn’t clear in an ensemble. DiMura has the chorus enunciate better. Still not clear enough. DiMura has the men drop an octave so their voices won’t cover the women’s. The words still aren’t clear. Then Ogborn solves the problem by changing the lyric.

Saturday, June 17. Stage Manager Sabato unpacks a big box each day when she arrives. It contains items that she says are essential to her job — band aids, aspirin, antacid pills, five-and-dime reading glasses, extra batteries for cast members’ tape recorders. She says a stage manager has to serve as a resource, almost a mother-figure, for cast members. Finally she pulls out her piece de resistance: a bottle and wand for blowing bubbles. “That’s to keep the cast occupied during boring times, like when the composer and the director are re-writing.”

After today’s workshop Nolen, Ogborn and DiMura go to eat. Discussing media hype, Ogborn tells how the OJ trial inspired him to write Baby Case. Casually, he says, “You know, Jack Benny attended the Hauptmann trial.” “He did? exclaims Nolen. “Yes. He even told someone that what Hauptmann needed was someone to write him a second act.” Nolen says that might fit into the play, and Ogborn now is thinking of adding Jack Benny and his wisecrack to the script.

Sunday, June 18. An emergency develops. One of the cast loses her voice and runs to her doctor who tells her she tore a vocal cord and must not sing for several weeks. She is one of five who also are in the cast of Into the Woods, which is finishing its six-week run today. One of the others says that she has a cold, and she realizes that singing two shows while fighting a cold can be dangerous. She says she feels shaky. Probably both of them should have been “marking” in rehearsals of Baby Case — just touching the notes lightly instead of singing full voice every day.

Monday morning, June 19. DiMura and Nolen audition singers to replace the ailing one. Also, Ogborn is up til the wee hours writing Mrs. Lindbergh’s big song. Will he finish it? Will it work? Stay tuned.

The second week is for changing songs and dialogue and adding some simple staging for the Saturday run-through. Ogborn will be writing and editing every day. “I know everything about this case,” he explains. “But the audience doesn’t, and I need Terry’s advice on what needs to be clarified. I’m depending on his good eyes and ears.”

At this Monday session, a new singer is hired and joins the rehearsals. In addition to songs, Nolen also asks her to make the sound of a baby crying. In this task she isn’t convincing, and Nolen says: “No good. You’re out. Hired this morning and fired this afternoon. This is a tough business.” He’s joking, of course, and she remains as part of the girl singing group — reminiscent of the Andrews Sisters —- that provides commentary throughout the show. Four of the other cast members audition their cries until Nolen finds the one that’s acceptable for the brief interpolation of a baby sound. Ogborn now unfolds the new song that he’s written for Anne Lindbergh, “Touch of Gold,” but he and Nolen agree that it works best in the second act. So the problem of how to end Act One still remains.

Tuesday, June 20. A run-through of Act One, dialogue and music, from top to bottom. An early ballad for Lindbergh, “Lucky For You,” is cut, though Ogborn likes the song. Nolen says the play needs to be baby-focused, not Lindbergh-focused. Also, there are too many ballads close to each other. “Maybe it’ll come back at a later point,” suggests Ogborn. All the time that Ogborn was concerned about a new ending for this act, Nolen felt the original ending was okay. Now Ogborn agrees. The act will close with a reprise of the title song. Priorities have changed. “This act is working well,” Ogborn says. “It’s Act Two that needs work.”

Wednesday, June 21. Run-through of Act Two. More lines are being given to Winchell, whose staccato style is amusingly imitated by actor Scott Greer. And now, because he has so many lines, the character needs a song of his own. Ogborn takes a tune away from another reporter and gives it to Winchell. This is different from some New York productions where songs are taken from lesser names and given to the stars who’ll sell the most tickets. The Arden doesn’t do things that way, and this change was made because the character, not the singer, needed more music.

Thursday, June 22. Cutting a line here and a phrase there. Adding vamp music, or “safety,” to help actors with the timing of their entrances. Developing characterizations. During a break, Tracie Higgins, one of only three cast members who knew Ogborn before this workshop, talks about an evening of Ogborn songs she did at the Don’t Tell Mama cabaret in Manhattan. “The beauty is that he writes in so many styles and knows how to capture a woman’s soul.” Higgins has a dark sense of humor. She arrives carrying a shopping bag and another cast member asks what’s in it. “The Lindbergh baby,” she responds. “I call this bag my baby case!”

Friday, June 23. Moving into the large theater where the Saturday night performance will take place, the actors now are seated in a semi-circle. DiMura, at the piano, conducts a complete run-through while the director and composer sit where the audience will be. When the cast takes a break, Nolen, Ogborn and DiMura huddle to discuss what worked well and what didn’t. Michael furiously scribbles changes on the script. When the cast reassembles, Michael sits cross-legged on the floor in the middle of the semi-circle while Terry crouches next to him. They take turns giving notes. Ogborn tells them what lines to cut, Nolen instructs them in interpretation. He sums up: “With all that we’ve cut, you’ll have plenty of room. Don’t rush. There’s no hurry. Each of you be aware where your narrative responsibility lies. Build up to your important lines and then really nail them.”

Saturday, June 24. Work on some isolated numbers, then —- even though it’s the day for the public performance — another complete run-through starting at 3:30. Fearing that he might be pushing his singers too hard, Nolen tells them to sing softly. The cast finishes after 6 and Nolen gives them a few more last-minute changes in the script. One of the cast announces that he’s volunteered his apartment for a party later.

Saturday night, June 24. In New York, investors and talent agents come to the final run-through. Here, the local equivalent of the money people are the Arden board members. They attend, along with over 300 citizens who line up to be admitted on a first-come basis. The cast are in nice outfits for a change, all the men wearing shirts and ties, director Nolen wearing shirt, tie and jacket. But look at conductor DiMura! He’s wearing a military jacket straight out of Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

The audience reaction is excellent: total concentration during quiet moments and enthusiastic applause after the big numbers, despite the fact that cast members make a couple of errors in the lyrics. Ogborn and the Nolens sit side-by-side in the third-from-last row of the audience. Michael leans forward and bounces with the rhythms. Terry mostly leans back and concentrates with less obvious emotion. At the end, Terry reaches over and shakes Michael’s hand. The cast beckons and both come to the stage. Michael drops to his knees to thank the cast, then rises and bows to the audience. Terry says how courageous Ogborn is for allowing the many changes that were made in his script.

Afterwards, the Arden Theatre announces that Nolen will direct a second workshop of the show in spring 2001, and will helm a fall 2001 production as part of the company’s subscription season.

The Second Workshop

June 11, 2001. The cast assembles in the same place as last June. More than half are holdovers. The new ones include a Philadelphia favorite, Jeffrey Coon, who was unavailable at the time of the 2000 workshop, and Sharon Sampieri, a young actress from Mount Laurel, New Jersey, who was discovered by Arden executives at an open audition and given the ingenue role last month in the Arden’s production of The Baker’s Wife. Nolen is trying Coon as Charles Lindbergh and Sampieri as Anne Morrow Lindbergh. Nolen feels that Mary Kate McGrath, at 5′ 5″, is too tall to play the diminutive Mrs. Lindbergh and he’s reassigned her to another part. Most people don’t know or care that Mrs. Lindbergh was short, but Nolen is a stickler for appearance. He says that some people have seen photos of Anne Lindbergh and would be bothered if the actress didn’t resemble her.

Ben Dibble, who sang the role of Lindbergh previously, will be given a different assignment. Scott Greer, who was Winchell, now is starring in the demanding role of Orson Welles in the play It’s All True at another theater, so he’s unable to repeat his portrayal of that journalist. Ogborn says he still wants Greer for the production in the fall. Nolen has several other singers try the part, and chooses Michael Holmes for this two-week workshop.

The procedure of this workshop is very similar to last year’s. Even the holdover cast members need to re-learn their parts. That’s not because they’re forgetful. “Actors remember what they need to know for the job at hand,” explains Nolen, “but after a play ends, they tend to put it behind them and learn something new. So they need to be refreshed.”

Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday are spent practicing the music. Then a full eight-hour day is spent learning “Wake up, New York,” the new Act One finale that Ogborn wrote a month ago. He tells us that he got the inspiration listening to a tape of the 2000 workshop. “Suddenly Scott Greer’s voice jumped out at me, delivering the spoken line ‘wake up, New York.’ I said to myself that I should write a song based on that.” It replaces a reprise of the song “Baby Case.”

Friday and Saturday, Act One is rehearsed with dialogue and music, putting the book and score together and running it through. The second Monday sees a review of “Wake up, New York” and Act Two is begun. Tuesday they finish Act Two, and on Wednesday the tech people come in and look over the production, measuring where props, scenery and projection screens will be placed for the staged version in October, and timing how long it will take to go from one scene to the next. Because the tech people need to see the cast on the main stage, Nolen moves rehearsals onto that stage for the final week. “I want you to become comfortable in this space,” Nolen tells them. “And please don’t try to fill the hall. Don’t push your voices. Just sing to us here at the front table.”

The weekend public run-throughs will use amplification. A technician sets up microphones and starts to test them. He mischievously asks the cast: “Do you know how many sound techs it takes to put in a lightbulb? One, two, one, two…”

Nolen explains the reason for this second workshop: “We’re making sure the through-line of the story is clear, so nothing will have to be cut after we start rehearsals. This is important because expensive sets will have been built, and costumes made, and we don’t want to have to scrap them after we’ve spent all that money.”

No songs have been cut since the previous year. Two new ones have been added —- “Wake Up, New York” and “Highfields,” which the Lindberghs sing at their new home before the kidnaping occurs. “A Mother’s Son,” written last year for Anne Lindbergh, is now sung by the female radio trio. Ogborn has written new harmonies for many of the songs, and more harmonic changes will be made on the spot as this workshop progresses.

Throughout the final week, whenever the composer and director go into a creative huddle, DiMura re-rehearses some of the music. So there are hardly any dead moments and Pat Sabato’s bubble-blowing kit isn’t needed. The timing is 2 hours and 25 minutes, including intermission, so nothing needs to be cut for time considerations. Trims may still be made for the sake of clarity.

Public sessions take place Friday and Saturday nights. The solos and ensembles are polished, every word pronounced clearly and understandably. Coon and Sampieri are excellent as the Lindberghs. Special laughter and applause greet the photographer’s number, “A Picture of You,” done by Richard Ruiz, the tenor who was unknown until last year’s workshop. Ben Dibble has moved over from Lindbergh to the part of Hauptmann and his big song, “No I Never Did,” is taken a bit slower than last year. This makes the words clearer and when Dibble nails the high note at the end he receives an enthusiastic ovation, the longest of the evening.

The World Premiere

Now director Nolen and composer Ogborn have three months to prepare for rehearsals which start in September, leading to an opening night on October 11, 2001. In this final period, cuts are made in dialogue about the appeal process after Hauptmann’s conviction. Leave that for the history books; this is a drama and it needs to move forward. “Highfields,” the Lindberghs’ duet about their home, is ditched and a new song is added for Charles Lindbergh. Early in the workshop process an opening ballad for Lindy was cut so the show could move more quickly to the kidnaping. But he’s the play’s most-famous character and audiences will want to hear more from him. So he gets a new aria in the second act.

Although this seems contrarian, it highlights what the workshop process is all about. Only by trying things can an author and a director discover what works. Ogborn talks with us about the changes: “It’s funny how you think some words are important, then you cut them and you realize you didn’t need them after all, and the play works better without them.”

The most notable thing to emerge in the final rehearsals is the timeliness of the script. The targeting of foreigners and lyrics about unknown assailers roaming the streets of Manhattan, in the “Wake Up, New York” scene, have an eerie sound after the horror of September 11.

For the stage premiere, the cast is one-third larger than at the first workshop. There are 24 actors and DiMura conducts a ten-piece orchestra. The play is received enthusiastically and reviews are excellent. The Philadelphia Inquirer says “Crime of the Century yields the season’s best musical.” Baby Case has had few revivals since its successful production in 2001. Mostly that’s because it requires a very large (and, therefore, expensive) cast. Still, even though Baby Case has not become widely-known, this chronicle provides an interesting look at the process of how any new musical is developed.

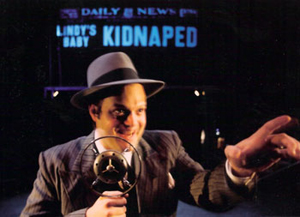

Below, Greer as Winchell. Photo by Mark Garvin: