Leonard Bernstein’s Symphony No. 1 was the major undertaking at the Philadelphia Orchestra’s concerts of May 3, 5 and 6, 2017. Yannick Nézet-Séguin led the piece as a prelude to a year-long celebration of Bernstein’s centenary. (He was born on August 25, 1918.)

Bernstein began writing the piece in the summer of 1939, right after his graduation from Harvard at the age of 20. Concerned about the plight of Jews in Nazi Germany, he wrote what he called a “Hebrew Song” for soprano and orchestra, based on the biblical Book of Lamentations. Then he put it aside as he became a freshman at the Curtis Institute.

He included a version of that song in a three-movement symphony in 1942, which he called Jeremiah. The titles which Bernstein gave to the three movements — Prophecy, Profanation, Lamentation — sound a bit pompous but the last of the three is crucial. It is Bernstein’s vocal setting of part of the Book of Lamentations, about the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 BCE. (Scholars once thought, but no longer, that the book was written by the prophet Jeremiah.)

Bernstein’s conducting professor from Curtis, Fritz Reiner, suggested that Lenny’s music could find an audience if he added a fourth movement because, as Bernstein related, “[Reiner] insists it’s all too sad and defeatist.” Bernstein refused. Exhibiting the brashness of his youthful personality, Bernstein said “I seem to have had my little say as far as that piece is concerned.” Mutual friends who knew Lenny in those days told me that one of the most delightful aspects of his personality was his assertiveness, sometimes with an edge of rudeness.

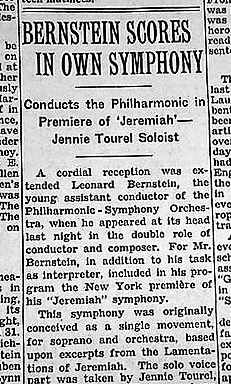

In November 1943 Bernstein made his conducting debut with the New York Philharmonic as a substitute for Bruno Walter, which propelled him to fame. Reiner invited LB to conduct the premiere of this Symphony No.1, left untouched as Bernstein insisted, with the Pittsburgh Symphony on January 28, 1944. Within the following year, Bernstein conducted it with the Boston Symphony, New York Philharmonic, and in Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit, Rochester, Prague and Jerusalem.

Yannick’s conducting of the symphony, this week in Philadelphia, started boldly and assertively, with pulsating brass chords in dissonance with weepy violins and whispering bass fiddles. The movement projects the patriotic fervor that accompanied America’s entry into World War II. It includes variations on the musical theme of the Amidah, included in synagogue worship as 18 benedictions that declare praise for God.

Peculiarly, Bernstein at the time denied that he quoted Jewish liturgical melodies. Was he embarrassed to admit that he had? Those were days when it was rare for Jews to speak out and to identify as Jews. Bernstein even considered changing his last name to Amber to disguise his religion. Most likely in this instance, he was reaching out to a diverse public, trying to envelope everyone.

The second movement is a scherzo that portrays destruction and chaos. Bernstein later admitted that he based this middle movement on his bar mitzvah portion, “derived, note for note”, sped up and “rhythmicized.” To our ears, today, it resembles the Latin music in the gym scene of West Side Story. Bernstein’s irregular rhythms derive from his familiarity with the non-metrical structure of the Hebrew language, which is based on the alternation of syllables, without regard to meter.

The third movement, in Bernstein’s words, “is the cry of Jeremiah as he mourns his beloved Jerusalem, ruined, pillaged and dishonored.” Sasha Cooke eloquently sang the tune which repeatedly goes downward, expressing outrage and defiance. The Hebrew words are about Jerusalem—“How doth the city sit solitary”—but the city’s name is used as a representation of all Jewish life which was being exterminated. A quiet woodwind and strings postlude suggested a glimmer of hope.

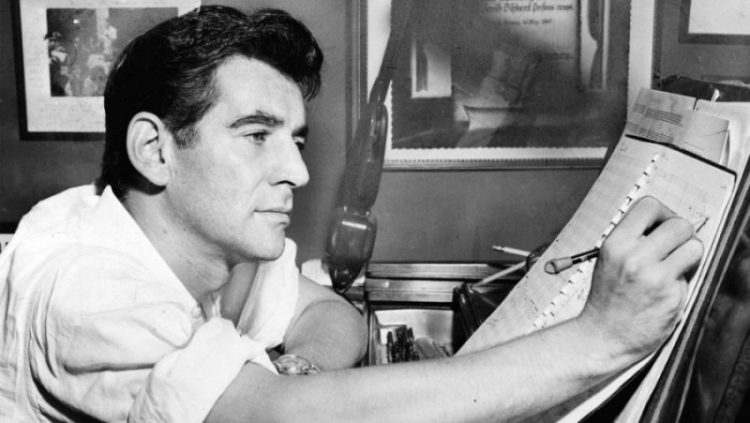

To the right, the young Bernstein:

Romanian-born Radu Lupu joined the orchestra for Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 in C-minor which is one of his rare concerti in a minor key. The 71-year-old pianist is white-haired and bearded like a patriarch. If you love Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G-minor, as I do, you’ll appreciate the wistfulness of this concerto. Lupu played very quietly. In particular, the second Larghetto movement has a lovely simple melody which seemed almost free-form, and Lupu explored it reflectively.

Indeed, Mozart seems to have been experimenting with this piece. He took his time; the concerto is one of his longest. He wrote several anticipatory endings and he never got around to composing the expected cadenzas to lead-in to the conclusions of his movements (Lupu invented his own). Sometimes the music seemed to be beautifully suspended in mid air.

Robert Schumann’s Symphony No. 2 was an appropriate companion piece to the Jeremiah because Schumann was apprehensive when he started work on it. The symphony sounds pessimistic, exemplified by a melancholy bassoon in the Adagio. Some people find jubilation in the first movement, but I’m struck by the slight dissonance between brass and strings. Schumann referred to it as a contrapuntal combination of two distinct melodic lines; but you might say it’s a bit schizophrenic. Parts of this symphony show Schumann asserting positive energy in defiance of his ill health. Yannick made the brisk scherzo sound especially exciting, and the finale was majestic and uplifting. Schumann had delusions about being poisoned, and he attempted suicide. Syphilis led to dementia praecox and he was committed to a mental asylum. He died at the age of 46.