Cy Coleman became a friend of mine during the last years of his life. We bonded, in part, because we both were middle-aged fathers of young children. And because we both had trained as classical pianists.

Cy Coleman was Broadway royalty, with more hit shows than any American songwriter living after 1980. The website of ASCAP called him “a permanent jewel in Broadway’s musical crown.” His shows are from the same classic fabric as Richard Rodgers and Irving Berlin. But not quite. Would any of those icons ever compose a song titled “Don’t Fuck Around With Your Mother-In-Law”? Not likely. Cy Coleman did, demonstrating that he mixed classic tradition with flip modernity.

Coleman’s personal life, too, was full of surprises. In his seventies he became the father of a daughter, Lily. He married for the first and only time when he was 68.

Lyric-writer David Zippel says “Cy never wanted to do the same thing twice. He was always looking for a fresh, original way to tell a story or write a song. He always looked for a creative challenge. Each lyricist — and I’m happy to be one of them — sparked a different chemistry.”

Coleman was born Seymour Kaufman in 1930, the youngest child of a New York carpenter, Max, and his wife Ida who gave Seymour piano lessons when he was four. “My mom owned four tenements in the Bronx and that’s where I grew up,” he told me. “When some tenants skipped out without paying the rent they left an upright piano, my parents moved it down to our apartment and that’s when I started to play. Then my parents bought an old farm in Monticello, New York, in the Catskills for $500 down, right across the road from Kutsher’s resort hotel. My dad did the carpentry and they built a bungalow community.

“My parents spoke Yiddish around the house and so did a lot of people in the Catskills. My mom took me into New York sometimes to see Yiddish theater on Second Avenue. I remember seeing Molly Picon on stage there. And I remember the way they always put happy endings on every play. Hamlet lives happily ever after! We used that in the plot of our show, The Great Ostrovsky, about a fictional, larger-than-life star of Yiddish theater in the 1920s.”

Ostrovsky had its world premiere at the Prince Music Theater in Philadelphia in 2004 with book and lyrics by Avery Corman, best known as author of Oh God and Kramer Versus Kramer, and with music and additional lyrics by Coleman. Coleman died a few weeks later, suddenly, of a heart attack in New York City. He was 75.

“My parents liked klezmer music but didn’t have any musical abilities,” said Coleman, “nor did my older siblings. I was the youngest of five. But they gave me piano lessons.” He became a child prodigy, training with the famed Adele Marcus, played at Carnegie Hall and entered the New York College of Music in his early teens. “Then I rebelled,” said Coleman. “I wanted to do something on my own. The college said okay if you don’t want to study piano anymore, you can be a conductor, but I said no to everything. There was something else I wanted to try.”

“I became a piano accompanist for classical, pop and jazz singers and that led to my start as a composer about age 16. As a pianist, I was accompanying a woman, Adrienne Matzenauer, a former Broadway singer whose husband was a producer, Michael Myerberg. They sent me to a publisher they knew named Jack Robbins. Robbins wanted to bill me as ‘the new Gershwin’ and he asked me to write Gershwin’s 4th, 5th and 6th preludes — in other words, to pick up where Gershwin left off, as if Gershwin actually had composed such pieces, and Robbins published them.” [Gershwin died after writing three piano preludes.]

“But first, Robbins decided that he had to give me a more commercial-sounding name. He said: ‘We’re going to change Seymour Kaufman to Cy Coleman.’ Nobody liked the name Seymour, it was so nebishy, so I was glad to change that to Cy, and he said the change of last name wasn’t too extreme: ‘It’s close, and it’s not like you’re trying to escape. Everyone will always know you’re Jewish.'”

“I called my mom and she said, ‘You want to change your name, be my guest. Do whatever makes you happy, Seymour.'”

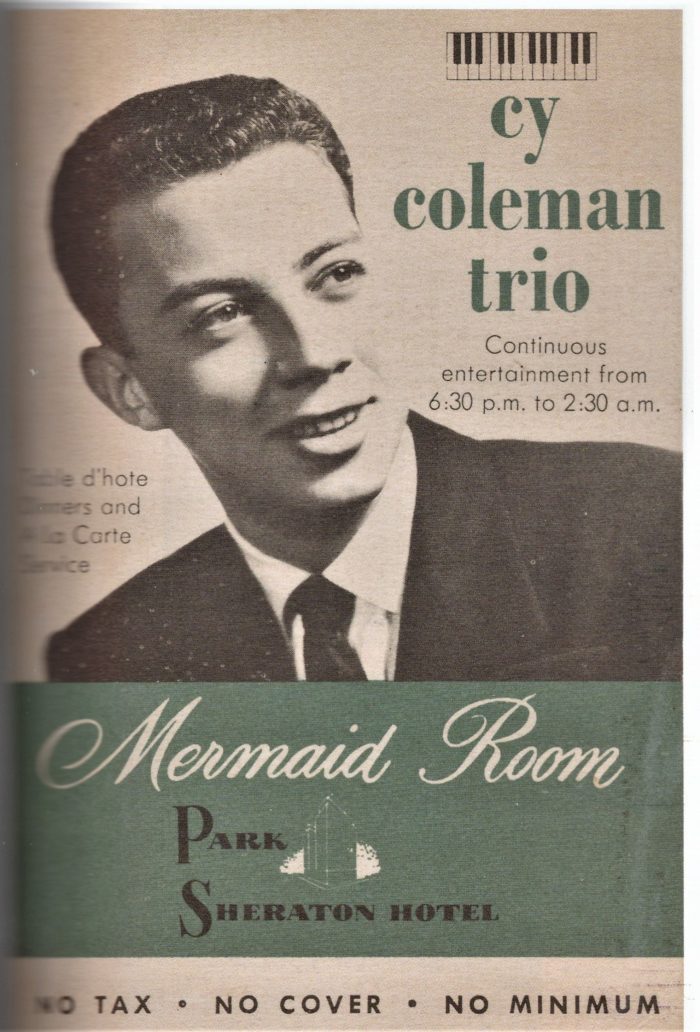

Deciding to leave classical behind, he formed a jazz trio and began playing in clubs: “originals and standards, mainly Rodgers and Hart, and I used my technique too much, actually, at the beginning. I made things too flashy. The hardest part of doing jazz is to get the feel. Gradually I listened to the people I was with, like Ray Brown and Jo Jones, and relaxed and got into it.”

One of Cy’s early gigs was as the pianist at a Second Avenue club named Le Perroquet. Variety reviewed him there in May of 1949, when he was 19: “A pianist with a classical background, this teenster distinguishes himself with fanciful melodic patterns, individualistic interpretation and mature styling. Coleman has a fresh approach which takes him on non-commercial cadenzas with complicated counterpoint best understood by Carnegie Hall pewholders.”

One of Cy’s early gigs was as the pianist at a Second Avenue club named Le Perroquet. Variety reviewed him there in May of 1949, when he was 19: “A pianist with a classical background, this teenster distinguishes himself with fanciful melodic patterns, individualistic interpretation and mature styling. Coleman has a fresh approach which takes him on non-commercial cadenzas with complicated counterpoint best understood by Carnegie Hall pewholders.”

Coleman played opposite Sarah Vaughan at Café Society and Ella Fitzgerald at Bop City. “Ella said to me ‘Cy, you’re never going to be louder than me, or louder than Illinois Jacquet doing ‘Flying Home,’ so just take it easy. Play softer.’ That was good advice.” He began to use as a model Erroll Garner and, later, the even-gentler Oscar Peterson.

“Serge Oblinsky was a columnist for the Herald Tribune and he praised my club work. Serge also ran the cabaret at the Sherry Netherlands hotel and he hired me to front a trio there. I came down from the Bronx on the subway and in my opening night audience I had Astors and Vanderbilts. What a contrast. They used to say ‘Cy, you’re playing too loud’ and I said ‘If you didn’t talk so loud I wouldn’t have to play so loud.’ I was a wise guy then. But they loved me, they extended my run and I literally moved into the Sherry Netherlands. I did ‘Date in Manhattan’ every morning for five years on New York’s local NBC station, and was a frequent guest on Kate Smith’s show. I had a big following.”

“We played every nice club in New York —- places that no longer exist, like L’Aiglon, Perigord and Mabel Mercer’s. We made recordings and I was on TV all the time.” A video clip of Coleman at the piano from that era shows him wearing a narrow black tie and a sly smile. Coleman began a lifestyle that included lots of women but no commitment until he was middle-aged. “Working in nightclubs, when you’re in the spotlight, pretty women find you. I’d gets notes from people in the audience.” Photos show that Cy had a cute appearance, but he told me that didn’t matter; girls were attracted to him because he was a performer.

Coleman found it easy to compose. “I don’t know how or why. It was natural. My whole life was music.” As a club player Coleman wrote many of his own tunes and scored a big pop hit with “Why Try to Change Me Now.” Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett and others had hits with later Coleman songs like “Witchcraft” and “The Best Is Yet to Come.”

“An executive at MCA offered me the job of fronting a big band which would play eight weeks at the Waldorf and tour the country. I said ‘I’m sorry, Mr. Dugan, but I want to do something more creative.’ He was angry. He got up from behind his huge desk, walked around and pointed a finger in my face and said ‘You’re through in show business.’ At 18 or 19, you get scared by that.”

“My first lyric-writing partner was Joe McCarthy, Jr. His father wrote ‘Alice Blue Gown’ and ‘I’m Always Chasing Rainbows.’ Joe was ten years older than I was and his paternalism bothered me. We had a clash of personalities. Joe was a very slow worker, and he drank too much, which slowed him down even more. Our song ‘Why Try to Change Me Now’ was put on the B side of ‘Birth of the Blues,’ Sinatra’s last hit for Columbia before Mitch Miller dropped him. So it sold a lot of copies and some people even turned over the record and listened to our song. It did stick around. Then Nat King Cole recorded ‘I’m Going to Laugh You Right Out of My Life,’ our second hit.”

“I moved to 58th Street in a brownstone above the Italian restaurant Vicario’s. The owner of that place bought The Playroom down the block and he said to me ‘Cy, if you play at my restaurant I’ll give you half interest.’ It was the worst decision I ever made, because the employees robbed me deaf, dumb and blind. Jackie Gleason used to bring friends in several times a week and William Holden practically had a reserved bar stool but I wasn’t making any money. At that time I started writing with Carolyn Leigh and we had a big hit with ‘Witchcraft.’ I was disgusted with the nightclub so I quit that and started to write full time with Carolyn. We wrote a score to a Thurber story and Abe Neuborn, our manager, managed to get us an advance from Feuer and Martin to do a show called Skyscraper. It never developed until years later and by that time we weren’t part of the project. Meanwhile James Van Heusen and Sammy Cahn were doing a show for Lucille Ball called Wildcat. They fought over something and the show needed a new songwriting team so the choreographer, Michael Kidd, recommended Carolyn and me. We tried it out at the Erlanger in Philadelphia in 1960 and our biggest song in it was ‘Hey, Look Me Over.'”

[By coincidence, when Skyscraper finally made it to Broadway in 1965 it was with a score by Cahn and Van Heusen.] One night in Wildcat a little dog in the show walked center stage and pooped. Valerie Harper, who was in the ensemble, described how all the dancers were backstage, dressed in white and waiting to do a Mexican Hat Dance. Before they went on, Ball hightailed it offstage and then came back on with a dustpan that she used to scoop the poop. Lucy then turned out to the audience and deadpanned, “Next time, I’ll read the fine print in my contract.”

One night in Wildcat a little dog in the show walked center stage and pooped. Valerie Harper, who was in the ensemble, described how all the dancers were backstage, dressed in white and waiting to do a Mexican Hat Dance. Before they went on, Ball hightailed it offstage and then came back on with a dustpan that she used to scoop the poop. Lucy then turned out to the audience and deadpanned, “Next time, I’ll read the fine print in my contract.”

According to Coleman, singing was not one of Ball’s talents and, after the show opened, the director and the songwriters cut two of her six songs. But Wildcat was a vehicle for Ball’s comedic acting and when she left, the show was doomed. “She met Gary Morton and fell in love with him. Shortly after that, Ball collapsed on stage, or pretended to, and said she needed to take time off. What she did was take off for London and marry Morton. She was gone nine weeks and didn’t pay the musicians while she was gone. (She was the producer, too, in charge of the finances.) The union wanted to be paid and I said to them if you charge her for the nine weeks she’ll say she can’t afford to re-open the show and none of us will get anything. But the union didn’t listen to me, they demanded that she pay them, and so she closed the show.”

Little Me was a successful 1962 collaboration with Neil Simon, Carolyn Leigh, Bob Fosse and star Sid Caesar. For the second time, a Coleman show tried out in Philly. “It was in the tryout that we made a crucial change,” he says. “Our first act finale was falling on its ass. It was a song that went: ‘Don’t you fret, Lafayette, we are here.’ We had cannons going off and Sid doing all his bits. It was exciting, but it just wasn’t working. Then Fosse said ‘Let’s try putting back the slow ballad ‘Real Live Girl’ to a ballet of soldiers.’ He was right. A loud number was wrong. We’d given the audience so much that they reached the saturation point, so they needed a change of pace to let it digest.”

“When Little Me was at the Erlanger,” Coleman recalled, “Bobby Fosse changed the staging of one of the songs, called ‘The Girls of 1917’, cutting a few lines out of the lyric. My partner, Carolyn, was furious and she ran out of the theater onto Market Street, made a left turn and ran towards City Hall. She found a traffic cop and brought him back into the theater where she commanded him to ‘arrest that man’ and she pointed to Fosse. She was an intense woman! We knew we had a hit when the cop asked if he could stay and watch the second act.”

Despite her faults, Cy was especially impressed by the way that Leigh took on the challenge of writing words to one of his quirkiest, jumpiest instrumental solos and turned it into “The Best Is Yet to Come.”

The collaboration of Coleman and Leigh was strictly professional. “She was a large woman, not my type. In fact she married two different men while we were partners. As you can tell from the story about the cop at the Erlanger Theater, she was very volatile. During one argument she told me, ‘Maybe you should write with someone else.’ So I did.”

“Bob Fosse asked me to do Sweet Charity in 1965. I knew him from Little Me, of course, and Dorothy Fields had done the lyrics of Redhead for him, so he put the two of us together. I actually had already met Dorothy at a party.

“Sweet Charity was Fosse’s re-imaging of the Fellini non-musical film, Nights of Calabria, with the main character changed from a prostitute to a dance-hall hostess. It was really a show for Gwen Verdon who was married to Bobby at the time. Fosse wrote the first book for it, but he knew it needed more work so he flew to Rome to pitch the idea to Neil Simon, who was working in Rome on a film. Bobby wanted Neil because he was so talented, and we had all worked together on Little Me. Bobby showed up at Neil’s door and played tapes of our songs for him, ‘Big Spender’ and ‘If My Friends Could See Me Now.’ Neil didn’t want to do another musical, but our tape convinced him and he came on board.”

“Our show originally was a one-acter. Next time you see Sweet Charity you’ll notice there’s really no Act 1 finale. They’re stuck in an elevator, blackout, and the act just ends. Act 2 starts with them still in the elevator. The reason for that is that our show kept growing and getting too long and we had to turn it into a two-acter, so we just split it in half.”

On the right, Coleman with Gwen Verdon:

“I went back to my roots for one song in Sweet Charity. On the road, before Broadway, we needed a new song and I wrote a fugue! It’s called “The Rhythm of Life” and it’s a spoof of cult churches. I later realized that the melody was similar to the bridge in the 1952 movie soundtrack song for High Noon: ‘He made a vow while in state prison, Vowed it would be my life or his’n.'”

“I was in awe of Dorothy. She was the daughter of Lew Fields from the vaudeville team of Weber & Fields and she wrote hits with Jerome Kern in the 1930s. But she was only 30 when she worked with Kern so she wasn’t really old when she started working with me, only 60, but to me at age 35 she seemed old; she was from an older generation.”

“Dorothy was totally professional. She’d start every morning sharpening her pencils and sitting at a card table to write. When we worked together sometimes I’d feel intimidated and to break the tension I’d excuse myself to go to the bathroom and sometimes while I was in the bathroom a melody would come to me. Dorothy was very smart. Whenever we’d be stuck she’d say ‘Cy, go to the bathroom!’ She liked to work to music, so usually we’d pick a title and I’d write the melody or at least the beginning of a melody, and after that she’d start on the lyrics.”

Coleman and Fields created one musical that never was produced, Eleanor, about the life of Eleanor Roosevelt. Book troubles sidelined it, and then Fields died. Coleman says he liked the score, but all was not lost. “I kind of cannibalized it. I used tunes from it in Barnum, Will Rogers Follies, Seesaw — ‘It’s Not Where You Start, It’s Where You Finish’ — and a proposed-but-never-finished show, Napoleon and Josephine.

Getting back to Sweet Charity for a moment, Coleman tells of a song he and Fields had to cut from that show: “Oscar, who was Charity’s love interest, was originally brash, a Frank Sinatra type with an ‘I’ll show you’ personality. So we wrote ‘You Wanna Bet’ for him. But as we worked on the script his part became more neurotic and the song didn’t fit anymore and we cut it. We still needed a title song, so we wrote ‘Sweet Charity’ using the same tune as ‘You Wanna Bet,’ just with a different tempo.”

Cy resisted an offer to write music for the Comden and Green adaptation of the old comedy The Twentieth Century “because the perception was that it would be a 1920s musical and I didn’t want to get stuck writing in that style. But then Betty and Adolph came up with the idea that the whole show was like a comic opera, so I wrote an operetta type of score.” (On the Twentieth Century opened on Broadway in 1978 and was revived successfully in 2014.)

Other Coleman shows include Seesaw (1973) — his last with Fields, who died the next year — I Love My Wife (1977), City of Angels (1989), Will Rogers Follies (1991) and The Life (1997.)

City of Angels is one of Coleman’s greatest achievements, the story of a film noir author combined with that author’s fictional detective story. Its witty book is by Larry Gelbart and the lyrics are by David Zippel. Its music combines jazz, Hollywood and Broadway. Coleman also simulated film music, with underscoring during the dramatic scenes.

The idea for The Life came from lyricist Ira Gasman and Coleman worked on the show for almost two decades. It was a return to a mileu that Cy knew well — Times Square in the 1970s and 80s. Friends questioned the idea of writing about pimps and prostitutes but Coleman persisted. His songs for The Life reflected Cy’s empathy for underdogs and people who are disadvantaged. He supervised all aspects of the project and, to promote the show, produced a CD with pop and soul versions of the songs by famous personalities. Fund-raising was a problem, and so was the death of the show’s intended director, Joe Layton. When The Life finally opened in 1997 the reception was mixed, but Coleman was proud of his jazz-inflected, soulful score.

(In his fascination with the lifestyle of hustlers, Coleman reminded me of Sammy Cahn. At the end of this article, click on our story about Cahn under Other Broadway Songwriters.)

Cy also wrote a smaller musical with A.E. (Aaron) Hotchner about men thrown in jail for not paying alimony, originally called Welcome to the Club and re-written as Exactly Like You. On this project Coleman wrote his first lyrics, collaborating with Hotchner. “I do know something about lyrics, and I knew how I wanted the songs to sound. We worked closely together, and I did that again with Avery Corman on The Great Ostrovsky.” Because the characters used the F-word in their dialogue, “and because Mamet uses the word all the time in his plays,” Coleman decided to write that song about the mother-in-law for Welcome to the Club.

Patricia Birch, who co-directed and choreographed Coleman’s last show, said of Cy “He’s such an fountain of tunes. I like working with him because he really knows how to build a number. This show, Ostrovsky, is light, fun, a souffle.”

Coleman in 2003 wrote Grace, which premiered in Amsterdam to Dutch lyrics, about Grace Kelly, Alfred Hitchcock and the royals of Monaco. “Musically, I wanted to do a meld of European style and American style, the European feeling along with American pizzazz,” Coleman said. A. R. Gurney was working on an English-language version aimed at Broadway. Coleman also wrote for many films and won Tonys, Emmys and Oscars galore.

In 2004, just before his unexpected death, Coleman was at work on two other musicals. With David Zippel and Larry Gelbart he was writing a comedy, The Private Lives of Napoleon and Josephine, and Zippel, Coleman and Wendy Wasserstein were writing Pamela’s First Musical, a story about Broadway based on Wasserstein’s children’s book.

Zippel says that the Napolean musical will never come to the stage: “When Cy died, Larry and I looked at what we had, and we have about seven songs, or maybe eight songs, and part of an outline, and he and I talked about possibly finding another collaborator and finishing it. But it wasn’t at the top of our list of things to finish, especially with Cy gone. We didn’t work on it for a while, and then Larry died. This particular show, Larry Gelbart was the impetus for. He had a really kind of interesting, ironic take on their personal lives. It was sad and funny.”

Coleman told me in the fall of 2004 that New York might soon see an unusual musical that Coleman premiered in Los Angeles with lyrics by Alan and Marilyn Bergman, called Like Jazz. “It’s about the people who inhabit the jazz world, the people who play in it. About the lives of the musicians, the managers, the people who hang out in the bars. It started as a cycle of jazz songs and became a play about jazz.”

Six decades after he quit music college and began playing in clubs, Cy still had a special fondness for jazz and for that type of life.

To the right, Coleman in front of his keyboard:

Read about other Broadway songwriters by clicking here.