Daphnis et Chloé by Ravel, complete ballet music led by Yannick Nezet-Seguin with the Philadelphia Orchestra, November 2016.

The music world was shocked in 1912 when Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris presented the world premiere of L’Après-midi d’un faune (The Afternoon of a Faun), with music by Claude Debussy, conducted by Pierre Monteux and choreographed and danced by Vaslav Nijinsky.

One year later, the same company created an even bigger scandal with Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring) with music by Igor Stravinsky, also conducted by Monteux with choreography by Nijinsky.

Sandwiched between those events, Diaghilev’s company premiered Daphnis et Chloé with music by Maurice Ravel. The story also involved Springrime. Choreography was by Michel Fokine and Nijinsky danced the male lead. Again the orchestra was conducted by Monteux.

Sacre and L’Après-midi created sensations and are remembered as awesome musical landmarks. Daphnis et Chloé is hardly ever danced and, instead, is performed as a suite of orchestral excerpts. Performances of the complete ballet score by Yannick Nezet-Seguin and the Philadelphia Orchestra in November 2016 raised the question: Why the dichotomy?

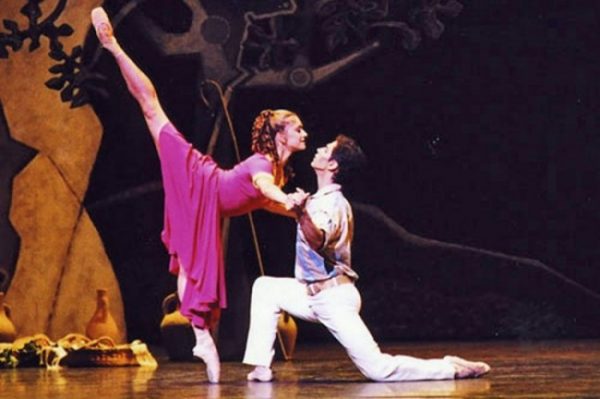

To the right, Nijinsky & his wife dance Daphnis et Chloé:

The reason is that Ravel’s music is so much less innovative. His entire career, as well as the juxtaposition of these premieres, followed Debussy’s.

Achille-Claude Debussy was born in 1862 and pioneered a form of music using nontraditional tonalities that portrayed mood and atmosphere. It was his conscious effort to create a unique French sound that was the antithesis of Wagner’s music which then was touted as “the music of the future.” His harmonic intervals and dissonances were original.

Ravel, 13 years younger, seemed to follow Debussy’s path. He was a meticulous craftsman but not a revolutionary. In comparison to Debussy and Stravinsky, Ravel was considered to be conservative and the premiere of his piece did not startle audiences the way the Debussy and Stravinsky ballets did. (Especially the Stravinsky with its spiked dissonances.)

Despite this, Daphnis et Chloé is a significant achievement. Ravel employed the largest orchestra he would ever require, including 15 percussion instruments, and he used them with consummate skill. At 55 minutes, it is Ravel’s longest composition. A wordless chorus adds “ahs” and “ohs” to the instrumental fabric.

Diaghilev complained about the employment of this chorus, because of the cost, but Ravel insisted on it. The familiar suite of Daphnis et Chloé does not include chorus, and patrons at the Nézet-Séguin concert commented that they never knew such voices were intended.

The large Westminster Symphonic Choir projected the vocals from the balcony (what’s called the Conductor’s Circle) above the orchestra’s level, facing out. Because of this unique vertical separation, the voices floated appropriately above the instruments. This is a phenomenon unique to the live event; the vertical separation can not be achieved in any broadcast or recording — and that’s why attending concerts is such a special experience.

Ravel’s conservative, fastidious style prevented his music from expressing the abandon and sexuality that marked The Afternoon of a Faun and The Rite of Spring.

Yannick’s interpretation turned this liability into an asset, as he brought out the score’s transparency and subtlety. While themes recur often (to the point where some listeners get restless), YNS’s meticulous attention to the singularity of each reiteration kept this listener’s attention.

Daphnis et Chloé was paired at this concert with Ravel’s subsequent Le Tombeau de Couperin and with Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 1, which was written before the Russian Revolution, thus sharing time period with the Daphnis et Chloé and which similarly had its premiere in Paris (Prokofiev’s adopted city.) Benjamin Beilman, a 26-year old graduate of the Curtis Institute, played it with elegance and ethereal peacefulness. The lyric opening movement is marked “sognando” — dreaming. That section ended with a quiet run of 64th-notes by Jeffrey Khaner on flute, curling upward. The concerto had a romantic aura, and its middle scherzo section displayed athletic playfulness, including spiccato (staccato bowing) and sul ponticello (bowing close to the bridge, which produces a buzzing tone.)

The congruence of the three compositions made this a meaningful example of program-planning. It also was an apt introduction to the Orchestra’s three-week festival of music connected to Paris, scheduled for January of 2017.

*

A personal note: The first Philadelphia performance of the Daphnis et Chloé ballet was conducted by my relative Saul Caston (whose real name was Solomon Cohen) in 1937 with the ballet company of the beautiful Catherine Littlefield.

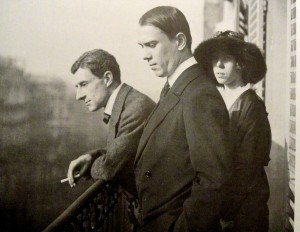

Photo below of Ravel, Nijinsky and Bronislava Nijinska in Paris 1914: