The headline quotes a lyric from “Laura”, the most famous song by one of the greatest film composers of all time.

“Some film composers change the face of the art form. In the course of doing their jobs, they leave a lasting impression on the industry.” —Filmscoreclicktrack.com

“He was one of the major figures in helping to free film scoring from the hold of 19th-century romanticism. His use of the orchestra and its instrumentation was unique and advanced for the time. He never presents you with a postcard photograph but rather an artist’s painting.” —Elmer Bernstein

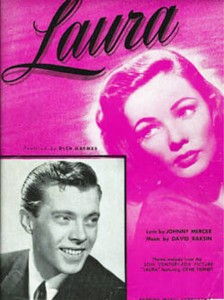

Gene Tierney & Dana Andrews in Laura

Raksin was the last of the movie musical titans to survive, living until 2004 when he was 92. At age 88 Raksin traveled from his California home to Joe’s Pub at the New York Public Theatre where he sang and played the romantic song “Laura” and excerpts from the scores he composed for films such as Laura, The Bad and the Beautiful and Forever Amber. That’s when I had the pleasure of meeting him.

Film buffs are in awe of Raksin. They usually, however, overlook Raksin’s Broadway work. He talked to me about Thumbs Up, a 1934 vehicle for the musical comedy team of Clark and McCullough, Paul Draper, Hal LeRoy and Eddie Dowling, staged by Robert Alton, and Parade, a 1935 review with a score by Jerome Moross, starring Jimmy Savo and also staged by Robert Alton.

“The pit bands in those days were 30 pieces or more,” remembered Raksin in our conversation, “not tiny like today. Orchestrators were not highly honored, we didn’t get credit in the programs and we weren’t paid much.”

Hans Spialek and Robert Russell Bennett were two of Raksin’s friends and colleagues in the profession. When I asked how his work differed from theirs, Raksin responded: “I was more of a jazz man. I was a jazz saxophonist myself, and I had a more youthful approach.” Two of the songs that were introduced in Thumbs Up were “Zing Went the Strings of My Heart” and “Autumn in New York.”

“My work on those shows was arranging, more than orchestrating.” The difference? “When we orchestrate we take the written notes and distribute them among the instruments of the orchestra. When we arrange, we do more. We re-arrange the composers ideas, and add material. The composers gave us a lot of leeway.” A probable reason why the composers gave away so much responsibility is the fact that so many new musicals opened on Broadway each season, so the song-writers didn’t have time.

Raksin was in his early 20’s, a recent graduate of the University of Pennsylvania’s school of music. He grew up in the Philadelphia Jewish pushcart neighborhood of Marshall Street. His father, Isidor, was a clarinetist with silent movie orchestras and a substitute player with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Then he became leader of the orchestra that accompanied silent movies at the Metropolitan theater. “On Saturdays, when I’d been a good boy, he let me go and sit next to him as he conducted.”

Young David studied piano and clarinet, then formed a dance band during his years at Central High, playing sax and clarinet and singing vocals on hits of the day such as Johnny Green’s “Body and Soul,” Gershwin’s “Embraceable You” and Rodgers and Hart’s “Isn’t It Romantic.” His small band was hired to play at Philadelphia radio station WCAU. He wrote some of the band’s arrangements, in addition to using stock arrangements which they purchased. When he went to Penn, Raksin played sax and piano for the Ipana Troubadors, a well-known radio band led by Sam Lanin, uncle of the later-to-be society bandleader, Lester Lanin.

“Trying to find work in New York, I was starving,” said Raksin. “Then Al Goodman, one of the best conductors of Broadway pit bands, played my arrangement of ‘I Got Rhythm’ and his pianist, Oscar Levant, recommended me to George Gershwin, and that led to me being hired to be an orchestrator and composer in Hollywood.” Raksin was pleasantly surprised, within the next few years, to meet many of the writers whose songs he had sung with his band.

“I think our country’s greatest cultural contribution isn’t so much jazz or blues; it’s the great American songs written by Jerry Kern and Harold Arlen and people like that,” said Raksin.

He moved to Hollywood at age 23 and joined other emigrés from Broadway such as the Gershwins, Rodgers, Hart, Kern and Arlen. He got a job as Chaplin’s assistant for what many consider to be his masterpiece, Modern Times, which was completed in 1936.

“Charlie was a marvelous talent,” said Raksin, “He was an amateur composer but he didn’t know how to write the music down or how to elaborate his musical ideas. That’s why he hired me. He had a tape recorder so he could record the melodic ideas that came to him. It must have been one of the first tape recorders in this country—they made them in Germany before anyone made them here—because the singer and pianist Michael Feinstein tells me that only wire recorders were available in 1935 and ‘36, but I know we were using a tape recorder.

“Anyway, one day I was alone in Charlie’s studio on LaBrea Avenue, and I recorded myself playing part of Prokofiev’s Third Piano Concerto—the very tricky, difficult first movement. Later, Charlie was showing some guests around his place and he explained that this was the machine he used to capture his inspirations. Charlie said: ‘Here’s what I thought of yesterday‘ and he turned the ‘play’ switch on the machine and out came Prokofiev. He was so angry he fired me. Al Goodman talked Charlie into re-hiring me.

“Charlie was a surrogate father to me. He was more than that. We talked every day, about everything, about politics. No question, he was a lefty. It was amazing that a man as rich as he still had a feeling for the hopes of ordinary people. I loved him.

“I’m really the co-author of the score of Modern Times. My function was to take Charlie’s little tunes and identify them, then make something out of them. Charlie had his own ideas about the development and what he wanted and didn’t want. The two of us used to sit there and argue about what went this way and what went that way. Like, for instance, if you’re doing a sequence such as in Modern Times, the stuff in the factory, that starts out with three notes repeated. Well, how do you get eight minutes out of that? So that was what I was there to do.” We’d argue about what instruments should play a certain piece of thematic material. And Charlie would say yes or no.”

“Chaplin could not write the music down, and he always had somebody working with him. For instance, the film before Modern Times, he had a co-composer named Arthur Johnston, who was a songwriter who wrote ‘Pennies from Heaven’ and ‘Cocktails for Two.’”

After Modern Times in 1936 Raksin returned briefly to New York to work on orchestrations for Rodgers & Hart’s On Your Toes. Hans Spialiek was the principal orchestrator for that show and he asked his friend Raksin to work with him. They divided the work on charts for four of the songs: “On Your Toes” and “It’s Got to Be Love,” where Raksin wrote practically all of the arragements, and also “Quiet Night” and “The Heart is Quicker Than the Eye.” Raksin found lyricist Hart to be cheerful and complimentary, but composer Rodgers sour-faced and gloomy. Raksin allowed his unhappiness with Rodgers to be visible, and got into a fight with him. The composer then told Spialek he could use David to get the show finished, but he had to stay out of Rodgers’ sight.

After that, he was offered work in England, where he met his first wife, the late actress Pamela Randell. They had one son, Alex, who became a journalist. “Then I went back to California to work as a composer at Universal Studios.”

Raksin’s biggest pop hit came about when Otto Preminger was directing the romantic mystery film, Laura in 1945. “At that time I was considered much too far out and insufficiently housebroken to be turned loose on anything better than a horror film. But I was the next in line for detective-mystery-stories. Al (Alfred) Newman turned down the job of composer because Preminger was a headache to work for, and Benny (Bernard) Herrmann turned it down because he didn’t like the story. I took the assignment. But Preminger wanted the score to be based on ‘Sophisticated Lady’ by Duke Ellington. I told him it was wrong for the character and, in any case, that song had 15 years of baggage. He asked what I’d propose in its place. On a Sunday evening I sat at my piano and came up with the melody for the principal theme. That weekend I got a letter from my wife asking for a divorce. From that pain came the inspiration.

“After the film was released, the studio got over a thousand letters asking where can we hear the melody again. I said: ‘Look, we’ve got a tune here that we can do something with.’ I gave it to Johnny Mercer and he wrote the lyrics.” According to ASCAP, “Laura” ranks just below “Stardust” on the list of most-performed American popular songs. The glamorous actress Hedy Lamarr was asked why she had turned down the title role in that film, and she said: “Because they sent me the script instead of the score.”

When asked why he didn’t write other pop hits, Raksin said: “A guy like me, I write complicated melodies. They don’t easily adapt into songs. My melody for Fallen Angel, though, was recorded as a ballad called ‘Slowly’ by Dick Haymes.”

After Laura, Raksin composed the impressive score for Forever Amber. “It starts with an idea I called a quasicaglia—a pun on the word passacaglia—which in this case was just a G minor scale. Two parts superimpose themselves over that and develop into a sicilliene which eventually turns into an extended melody.” The score includes an English-sounding processional and the five note-melody in the oboe and strings is based on a harpsichord sonata by Scarlatti.

Then he composed the music for the film The Bad and the Beautiful. “I was in Kay Thompson’s penthouse at the time. What I did not know was that Andre Previn was next door and could hear me at the piano. So I am struggling with the thing and the door opens and Andre says, ‘What the hell have you been playing in here’? I told him, and he asked me to play it through. So I struggled through it, and looked up at him when I finished and all he said was, ‘Lunch.’

“Six weeks later Previn came on the soundstage while I was recording that same theme with orchestra. And he says, ‘What a great piece! Marvelous. I’ve got to have it. I want to record it.’ Then I said to Previn, ‘You son of a gun, I played this for you in Kay Thompson’s place and all you could say was Lunch!’ Previn simply replied, ‘the way you play, who could tell?’”

The website filmscoresclicktrack.com commented: “Raksin’s lush score captures all the glamor of old-time Hollywood in its sweeping and memorable main theme, with constantly changing directions, and a stunning octave leap while the unstable chromatic harmonies underneath morph and modulate. A saxophone solo adds sultriness and a muted trombone pulls us back in time.”

Raksin’s theme from this film was also turned into a song, “Love Is For The Very Young” with lyrics by Dory Langdon. It was recorded by artists as disparate as Stan Getz and Arthur Fiedler. Raksin also wrote the lovely title song for the movie “Sylvia” which was sung by Paul Anka.

In 1984 Raksin composed the score for Suddenly which starred Frank Sinatra as a presidential assassin. “It was scored for strings and four horns and only had about 16 minutes of music, but minutes that really counted.”

Raksin composed the musicals If the Shoe Fits and The Wind in the Willows and incidental music for stage productions of Volpone, Mother Courage and Noah. If the Show Fits opened on Broadway in December 1946 and had a five-week run. Leonard Bernstein told Raksin that he enjoyed the songs in it. The book and lyrics were by June Sillman Carroll, who was the sister of Leonard Sillman, the man who produced the series of New Faces revues in the 1950’s. June wrote sketches and lyrics for her brother’s revues. Coincidentally, one of the shows Raksin orchestrated in the early 1930’s was The Earl Carroll Sketchbook but there’s no connection. June married a writer and illustrator named Sid Carroll, who was not related to the producer Earl Carroll.

Raksin also scored more than 300 television shows. He served for eight terms as President of the Composers and Lyricists Guild and he taught Composition for Films at USC.

Raksin became interested in the Communist Party in the late 1930s because of its opposition to racial and religious discrimination and to Naziism. “Those are negative reasons,” said Raksin. “You should say that I supported them because of what they were for: equal opportunity, and the working man as opposed to the rich owners of big businesses.” He joined the Party in 1938 but became critical of it when the Soviet Union signed a pact with Hitler in 1939 and Germany and Russia divided Poland between themselves. “I was asked to leave the party when I expressed opinions that were contrary to the party line.”

He remarried and divorced, and his son Alexander is a writer for the Los Angeles Times. In recent years David traveled the world conducting concerts of music written by himself and other film composers.

Concerned about who was watching out for his health at his age of 88, I asked Raksin if he lived alone.

“Not really alone,” he answered. “As a marauding man, I’m rarely alone.”

“Do you mean to tell me you have a sex life at 88?” I asked with the impertinence of relative youth, and he replied in the affirmative.

“Kinehora,” I said, with the Yiddish word that means ‘good for you,’ or ‘keep it up.’

Raksin responded with a fervent: “You said it.”

He died in 2004 at the age of 92 from heart failure.

To read about other Broadway songwriters, click here.