Edwin Forrest, the 19th-century Philadelphia actor, was arguably the first American superstar. Critics praised him, politicians wanted his endorsement and working men fought – even died – defending him. He was a matinee idol and he dabbled in politics, channeling the anti-British spirit of Americans who recently forged the United States.

Forrest was given the unusual honor of delivering the main oration at a Democratic Convention on July 4, 1838, instead of that party’s leader, the President of the United States, Martin Van Buren. Forrest was 32 years old and he could have gone on to a career in politics. And he was as scandal-plagued as any modern superstar, with an ill-fated marriage and an infamous riot that he inspired.

Forrest’s name is known in Philadelphia because one theater on Walnut Street bears his name and an 11-foot statue of Forrest stands in the lobby of another, the Walnut Street Theatre. The real Edwin Forrest wasn’t that tall, but he figuratively towered over other performers. And his outsized, over-the-top personality made him a controversial public figure with oversized human strengths and frailties.

His career is worthy of note not just for the mark it made in theater history. Looking back at the life of Edwin Forrest one can discover the early stirring of a national self image and a definition of Americanness.

The Philadelphia street just off Second and South where Edwin Forrest was born is now known, appropriately, as American Street. But in 1806 it was called George Street — named for George Washington. Edwin’s father was an immigrant from Scotland who worked as a clerk at the First Bank of the United States and died of consumption when Edwin was 12 years old. Edwin, or Ned, as he was called, got a job working with a ship chandler. He spent all his spare time reading the works of Shakespeare. At age 14, in 1820, he made his acting debut at the Walnut as Norval in James Home’s Douglas. The critic of The Aurora, a Philadelphia newspaper, wrote of his performance:

“We were much surprised at the excellence of his elocution, his self-possession in speech and gesture, and a voice that, without straining, was of such volume and fine tenor as to carry every tone and articulation to the remotest corner of the theatre.”

But good reviews weren’t enough for William Wood, the manager of the Walnut, who employed mostly English-born actors. He called Forrest into his office and told him that theater needed star actors to draw audiences. Forrest, in Wood’s estimation, lacked that star quality and therefore the Walnut would not re-engage him. Forrest perceived that the quality he lacked was English birth. Woods didn’t say so explicitly, but to Forrest the implication was clear. This helps explain Forrest’s resentment of British actors. In later years, after some provocation, he began to wage his personal Revolutionary War against the British.

After leaving the Walnut, Forrest joined a company that toured Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Lexington and New Orleans, where he stayed for a year, had success on stage and an intense romance with an older, French-American actress.

A New Orleans newspaper critic was impressed with Forrest’s acting and with his uniquely American style: “Let us support this tender sapling and prove to the pedants of Europe that our soil is fertile in genius and that her children know how to cherish and reward it.”

On the left, cartoon of Forrest as a symbol of strength.

The United States was 45 years young. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were still alive. Most actors working in America were either British or they were Americans of British birth. Even the few that were native-born copied the English acting style. But Forrest was individualistic. He felt that the plays of Shakespeare were his own birthright. Appearing in Albany, Forrest met the most famous Shakespearian of the era, the British Edmund Kean (1787-1833), playing Richmond to Kean’s Richard III. Kean was so impressed that he got Forrest the role of Iago opposite his own Othello in New York City. According to Forrest’s letters, as Iago he received a standing ovation “with deafening applause” and a salary increase to forty dollars a week.

Forrest changed the characterization of Iago from the normal brooding malevolence. Instead, he played him as “a superficially gay, dashing and lighthearted fellow” according to biographer Richard Moody. An example: Iago’s “Look to your wife. Observe her well with Cassio” was spoken in “a frank and easy fashion, suddenly changing to a hiss into Othello’s ear” on the last words of the speech. The audience reacted with gasps to Forrest’s delivery and Kean’s startled expression. According to an Albany reporter, Kean said to Forrest afterwards: “In the name of God, where did you get that?” and Forrest replied that it was instinct.

Kean urged Ned to move to England and continue his career there. But Forrest stayed in America and, within one year, in 1826, took on the title role in Othello at Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street Theatre. At age 20, he now was a star.

His salary in January, 1827, was $200 a night. Within a few more years, it reached $500 a night, making him the highest-earning actor in the world in the entire 19th century, making more than Kean, Macready or any of the Booth family. It was at this early point that he started offering annual cash prizes to authors who would write new plays on American subjects with American characters.

Shakespeare’s dramas were at the heart of Forrest’s repertoire. He loved the title role of Coriolanus and chose that character for his sculpture. “The Roman manliness of his face and figure, the haughty dignity of his carriage and the fire in his eye render his Coriolanus one of the most finished, striking and classical performances that was ever exhibited on the American stage,” wrote James Rees about Forrest in 1874. But it never was a popular success. In Forrest’s defense, it should be noted that no actor has ever made a hit out of Coriolanus. It is a play most remembered as a joke in Cole Porter’s song, “Brush Up Your Shakespeare:”

If you think her behavior is heinous/

Kick her right in the Coriol-anus.”

Despite that, it’s as Coriolanus, in marble, that today’s theater-goers see Forrest, looming high above his onlookers.

There are no recordings of Forrest’s voice. He died five years before Edison invented the phonograph. But there are detailed contemporary descriptions of his performances. “He had head tones that splintered rafters,” rhapsodized the New York World. His voice was deep and husky according to others. “He soared above all the Hamlets of the day,” wrote James Rees in 1827. Near the start of his career, Forrest played Hamlet’s mad scenes with intentional artificiality, as if he were feigning madness. This was counter to the prevailing tradition that Hamlet actually went insane. Forrest later changed and played the madness as real. It’s interesting to note that our generation validates Forrest’s first instincts and sees Hamlet as a rational man who feigns madness to fool the king.

A Pennsylvania critic described his portrayal of Hamlet in 1828: “Mr. F made a beautiful point in falling on his knees after the ghost had vanished, in an attitude of reverence.”

His Othello, Macbeth and King Lear were said to be fierce. Congratulated for his playing of Lear, Forrest once replied indignantly: “For God’s sake, sir, I do not play Lear. I am Lear!”

A critic wrote: “The tremendous grief of the crownless king, his awful wrath, his madness, his tears, his death – all these are drawn with a wonderful vividness and reality, which go straight to the heart. We remember nothing more touching than the struggles of the poor old man when he feels reason tottering upon her throne, and then yielding to the irresistible pressure of a mighty woe, sinks into the semi-oblivion of a harmless lunacy.”

Another critic said: “His bursts of passion are beyond the power of pen to describe; they are the outbreaks of an abused man driven to desperation by the cruel treatment of his daughters. Mr. Forrest’s delineation of the choleric king is extremely natural.”

In September 1836, Forrest sailed for England and made his first appearance in London as Spartacus, in the tragedy The Gladiator, at Drury Lane Theatre. During a season of ten months he performed in that historic theater the parts of Macbeth, Othello and King Lear. He was entertained by England’s leading actors, William Macready and Charles Kemble, and at the end of the season was complimented by a dinner at the exclusive Garrick Club in the West End. During this engagement he met Catherine Sinclair, a 19-year-old actress who was the daughter of a popular singer, John Sinclair, and at the end of the theater season Forrest married her. He was 31.

Although he toured the United States and Europe, Forrest kept returning to Philadelphia as his home base. It was America’s main city for theater. He played the Walnut, the Arch Street Theatre, the Chestnut Street Theatre and, after it opened in 1857, the Academy of Music.

Biographer Richard Moody said of Forrest: “No one carried the democratic fever to the stage with such fierce passion.” His style was unsubtle, aimed at to the galleries, and fans equated his style with masculine and American virtues. Reviews praised Forrest’s “fine face, manly figure and frank, honest stage deportment.” His most famous roles were Shakespeare’s tragic heroes, plus Spartacus, Damon in Damon & Pythias and the anti-British Irish rebel, Jack Cade. Forrest personally selected the Cade drama as a winner in one of his new-play competitions.

His style was bold and brassy, like the upstart nation itself. While English performers favored an elegant, intellectual style, Forrest pioneered an extroverted, heroic approach. This made him popular not only inside the theater but in barrooms and on the streets as well. He was a cultural rebel, striking a blow against British tastes that echoed America’s political rebellion against the Brits.

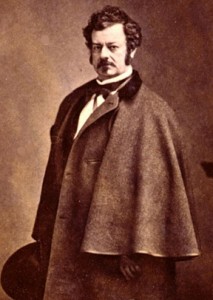

Below: Forrest portrait by Matthew Brady.

Forrest’s chief rival in acting was the Englishman William Macready, who epitomized the elegant English stage tradition. Forrest’s fans — known as Forresters — called Macready effete. In contrast, they bragged about their hero’s “manly,” barrel-chested build and his virile voice. They praised his “vital, burly Americanism.” These descriptions clearly went beyond acting and involved Americans’ definitions of themselves. Anglophiles showed their opinions of Americans by calling Forrest’s acting “vulgar and arrogant.” Macready’s friends included Wordsworth and Dickens. In contrast, Forrest said he was proud to be the friend of plain working men. Think, perhaps, of Sir John Gielgud compared to the young Marlon Brando.

David Howey, a veteran of Britain’s Royal Shakespeare Company who now teaches voice and speech at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts, says that the differences between Macready and Forrest carry over even in the 21st Century. “We were taught the ‘Macready pause’ his method of elongated pauses for dramatic effect. And we were taught ‘RP’ (received pronunciation), the standard dialect. There is an artificiality in British delivery and most Americans don’t like that. Sanford Meisner disparagingly called Olivier a ‘line actor.’ Even Sir Peter Hall criticized British actors for being ‘talking heads.’

“We British still focus our speech far forward in the mouth, which makes for more clarity. We are verbal and we feel the language must be played. We put our emphasis on communicating the words, whereas Americans put feelings first. That difference is more important than how one pronounces r’s and a’s. You know it was only in the reign of George III in the 1700s that the Duchess of Devonshire decided that flat a’s and hard r’s at the ends of words were vulgar, as in mother and father – and she had things changed. So we can’t say definitively how one should pronounce his r’s. Macready probably used softer r’s than Forrest, but Forrest may have been closer to what was spoken in Shakespeare’s time.”

The rivalry between Forrest and Macready came at a time when anti-British feelings again were escalating in America. By the start of the 1840s the Irish had become the largest immigrant group in America. Their numbers had doubled in the preceding decade, and they were intensely hostile to the British. The 1844 Democratic presidential candidate, James K. Polk, ran on a platform of annexing the Oregon Territory west of the Rockies up to the latitude of 54̊ 40′ – where it would touch the Russian territory of Alaska. The British protested, and said that land belonged to their possession, Canada. Polk was elected, thanks in part to the battle cry of “Fifty-four Forty or Fight!”

When Forrest appeared in a play at London’s Princess Theatre in 1845, Macready’s partisans hissed him. To get even, Forrest bought a box seat to a Macready Hamlet and stood up to hiss the Brit. Matters escalated when Macready came to America for the 1848-49 season. Forrest partisans disrupted a Macready performance at Philadelphia’s Arch Street Theatre. Macready sent notes of protest to the newspapers and Forrest responded with a note calling Macready “a superannuated driveler.”

Macready – only age 56, not really superannuated – wrote: “I cannot stomach the United States as a nation. Let me get out from this country and give me a dungeon or a hovel in any other, just so I be free of this.” Below, Macready photo.

A few months later, both actors brought productions of Macbeth to New York City, a mile away from each other. At Macready’s opening night as Macbeth, May 7, 1849, Forresters got into the theater, the Astor Place Opera House, and threw objects on the stage, knocking over props and temporarily halting the play. At Macready’s next performance, on May 10, guards were ready and they stopped young people who tried to get into the theater without tickets. A thousand Forresters gathered on the street and tried to break down the doors. They carried signs and leaflets saying “Workingmen: Shall Americans or English aristocrats triumph?” The Mayor of New York called troops to disperse the mob. In a scene reminiscent of Kent State in 1970, they fired on the crowd and 22 died. 100 were arrested. A newspaper said the crowd was made up of stevedores, pipe fitters, sailmakers, plumbers, butchers. The working class, in other words. They were mostly young and the mayor said, disparagingly, that many were “gang members.” Macready put on a disguise to flee the theater and the United States.

Right after the Astor Place riot, a fellow American actor said that the government should give Forrest a medal for driving Macready out of the country. But Forrest was disappointed to find that many newspapers criticized his followers for causing trouble, and blamed him for inciting them. Confused and upset and feeling some guilt, he retired from the stage for a year. Perhaps he regretted the growth of xenophobic, anti-British feeling. In any event, he refused requests that he run for Congress and thereafter avoided political involvement.

Not that he wasn’t wooed. Forrest was friendly with Andrew Jackson, the hero of the War of 1812 who later was elected to two terms as President. Jackson and Forrest were natural allies. Jackson’s parents came to the United States from Ireland just two years before he was born. When he was age 13, Andrew and his brother were captured by the British during the Revolutionary War. Thrown into prison, the two boys contracted small pox. His brother died, leaving Andrew hating everything British.

In the War of 1812, Jackson led the American troops in their greatest battle. He defeated British soldiers who, in the words of a Jackson friend, were “trying to get into New Orleans in search of booty and beauty.” Then, during America’s war against the Seminole Indians in 1818, Jackson executed two British subjects who had been supplying and advising the Indians. His action drew diplomatic protests from the British government but Jackson didn’t care. He remained angry with everything British and was proud of it. When he ran for President in 1824 and 1828, Jackson championed Western farmers and Eastern laborers, the “common people,” in opposition to the patrician, aristocratic John Quincy Adams. After losing in his first try in 1824, Jackson was elected in 1828 and re-elected in 1832.

Jackson’s base was ordinary men who detested those who had privileges. He cultivated that base when he vetoed a bill that would have extended the life of the Second Bank of the United States, a private company where the federal government deposited all its money, because Jackson claimed that one-fourth of the bank’s stockholders were foreign and most of the rest were Americans who got rich by trading with England. He opposed the bank because it served the interests of the wealthy at the expense of the common people. The public showed it was on Jackson’s side by re-electing him in 1832 when the bank was a key issue.

Edwin Forrest grew up just a couple of blocks from where the bank was located, on Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street. (Its Greek Revival building still stands there.) What’s more, Edwin’s father had a low-level job at the bank. But Forrest felt no attachment to it; he strongly supported Jackson’s actions. As Jackson completed his second term in office, Forrest was at the height of popularity and made his first appearances in London.

Five years after Jackson left office, Forrest visited the ex-President at his home, The Hermitage, in Tennessee, and Jackson’s friends asked Forrest to become a candidate for Congress. They thought that Forrest, because of his public stand against the British, would get votes from anti-British ethnic groups, including the rising number of Irish-Americans. It’s wild to think that an actor’s opinion of foreigners would attract such public attention, but in fact it did. His staunch patriotism and his identification with heroic characters would have made him an attractive candidate, but he declined to run.

Another American president was a fan of Forrest’s – Abraham Lincoln – and his enthusiasm for the actor’s work led indirectly to his assassination. An English actor named Junius Brutus Booth was a rival of Kean, whom he was thought to resemble. Booth played Iago to Kean’s Othello on several occasions. Junius came to the United States in 1821 and established the Booth name upon the American stage. His theatrical legacy would be carried forward by his sons Edwin, John Wilkes, and Junius Brutus, Jr. He named the eldest of these in honor of Edwin Forrest in 1833 when Forrest was only age 27 but already famous. Junius Booth’s second son, John Wilkes, was born five years later.

Plotting to kill Lincoln in 1865, John Wilkes Booth decided that the best place to strike would be at a theater because Lincoln often attended plays. Booth became even more specific. Abe’s favorite actor was Edwin Forrest, and Booth saw that the 58-year-old Forrest was booked to appear at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, which surely would compel the President’s attendance. Booth cased the building and found that it offered a clear opportunity to kill the President and to escape. When it was announced that Lincoln would attend a performance of Our American Cousin there on April 14, before Forrest’s arrival in town, Booth decided not to wait.

Instead of running for office, Forrest used his fame and wealth to help American playwrights. From 1829 to 1847 he sponsored contests for new plays about Americans, paid cash to the authors and put the winning works on stage with his own acting company. He left his fortune to establish a home for ill and aging actors.

Forrest on cover of Harpers Weekly in 1866 (on the right):

The first site for the Forrest home for actors was Edwin’s summer residence, Springbrook, which he built in 1865 on 100 acres in Northeast Philadelphia. He stipulated that it be made into a retirement home for actors after his death. In 1926 the city bought that acreage and Forrest’s estate opened a new home at 4849 Parkside Avenue, adjoining Fairmount Park. It remained in use until 1986.

The residents were from all aspects of theater: vaudevillians, Shakespeareans, comedians, extras. There was a maximum limit of only 12 residents at a time, because Forrest wanted it to be a real home, not an institution. The residents lived among souvenirs of Forrest’s career – photographs of Forrest by Matthew Brady, costumes, suits of armor, daggers, dueling pistols and knives, including some Bowie knives given to Forrest by their inventor, Jim Bowie, who was one of his friends. There also was a huge statue of Forrest as Coriolanus, which later was purchased by the Walnut Street Theatre where Forrest had made his debut.

The Forrest Home merged with the Actors Fund of America in 1986 and its residents moved to the Actors Fund Home in Englewood, New Jersey. On Shakespeare’s birthday each year a luncheon is given there, with entertainment by Broadway stars. Gloria Justin, past president of the Edwin Forrest Home, explained: “He was a wonderful benefactor for his fellow actors, and the beautiful thing is that he started his good works in his youthful days when he built his mansion on Broad Street and said he’d donate it to elderly actors. But he lost that house in that messy divorce.”

“Messy” is an understatement. Forrest’s problems with Macready and the British may have played a corrosive effect on his marriage to the young English actress, Catherine Sinclair. Certainly the problems between Edwin and Catherine escalated as the feud with Macready became intense. A split-up occurred just a few months before the Astor Place riot. Forrest was appearing in Cincinnati as Othello and his Iago – the man who inflames Othello’s jealousy – was an actor named George Jamieson. One afternoon in December, 1848, Forrest went to a portrait artist for a sitting, leaving his wife alone in their rooms at the City Hotel.

Forrest told the story himself, in an affidavit: “When I came back and entered my private parlor I found Mrs. Forrest standing between the knees of Mr. Jamieson, who was sitting on the sofa with his hands upon her person. I was amazed and confounded and asked her what this meant. She said, with perturbation, that Mr. Jamieson had been pointing out her phrenological developments.” This eyewitness description astounded readers.

Forrest took no action that day, but in January, 1849, while his wife was visiting her sister, Forrest broke into a locked drawer and found a romantic letter to her from Jamieson. After that, Forrest ordered her out of the house. Her lawyers claimed that Forrest had affairs with actresses and that one of them went to a doctor for an abortion. The eventual court ruling gave Mrs. Forrest all that she asked for in property and alimony. She stayed in the United States – in fact, later became manager of a theater in San Francisco.

Forrest never had any children. His brownstone mansion at Broad & Master Streets later became the home of the respected black company, Freedom Theatre.

In his sixties, Forrest was impaired by arthritis. Sometimes he had to lie prone on stage before the curtain went up, and had to be helped into position for each scene. He saw his popularity challenged by Edwin Booth, who used a less declamatory and more conversational delivery.

On the night of March 25, 1871, Forrest appeared in Boston at the Globe Theatre, as Lear. He played this part six times, and was announced to also appear as Richelieu and Virginius. But then he developed pneumonia. He struggled through a performance and it was reported that “rare bursts of eloquence lighted the gloom, but he labored piteously against the disease.” When offered medications, Forrest waved them away with the words, “If I die, I will still be my royal self.”

That was his last appearance as an actor. After that, the infirm Forrest limited himself to dramatic Shakespearian readings. He died in his sleep in December of 1872 at age 66.

Those who remember his exploits are ardent. Theater personalities Hal Prince, Celeste Holm, Barnard Hughes and Hope Lange were among the 240 members of an Edwin Forrest Society, pledging their money to help ill and aging actors in the Forrest tradition.

“Forrest was a big, over-the-top man who was representative of the tempest of his times, “ said writer/actor Will Stutts. “He was America’s first native-born actor, and a bounder who fell madly in love with a woman who was unfaithful.” A group of admirers gathers at Forrest’s tomb in Philadelphia on his birthday every March 9 to lay a wreath and drink a toast to his memory. Others observe a provision of Forrest’s will by gathering to read the Declaration of Independence aloud each July 4.

Stephen Sell, retired manager of the Annenberg Center, has led the graveside ceremonies in a courtyard at Third & Spruce Streets for several years. “We come together to honor him because he was important to Philadelphia and to the theater,” he says. Another devotee was Frank McGlinn, veteran supporter of the arts, who said: “This man was the first American actor to achieve fame in Europe. He was the highest paid actor in the world and he used his fortune to help other actors.”

But perhaps the highest tribute to Forrest is the fact that in January, 2000, fans bid against each other to buy a lock of Forrest’s brown hair that was clipped by a friend when the actor died. Bernard Havard, producing artistic director of Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Theatre, outbid all others at Lancaster, Pennsylvania’s Smythe Auction House to bring some Forrest memorabilia back to his theater. The price for Forrest’s curl: $325. In addition, Havard bought a glass caster from underneath Forrest’s bedpost, a calling card, a photo and playbills. The hair is in a frame, exhibited in the Walnut lobby across from the Coriolanus statue.

This might seem to verge on enshrinement, but it’s an earned tribute to an actor whose life was a legend even before his death and whose impact lasted far beyond that. Even the British seem to have forgiven him. He’s the only American actor to have his picture hanging in the venerable Garrick Club in London.

This article originally was a cover story in Philadelphia’s City Paper.

Read other reviews on The Cultural Critic