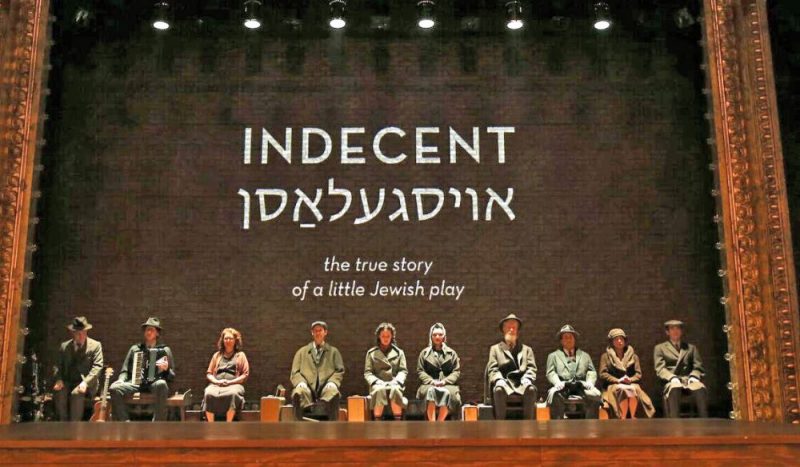

Indecent. Created by Paula Vogel & Rebecca Taichman. Written by Vogel, directed by Taichman. Cort Theatre, New York, through August 6, 2017.

Indecent is a daring play, in multiple ways. It involves interweaving stories about free speech and censorship; about immigration to America; about the hypocrisy of a religious man who puts his business interests ahead of his family. And it shows a lesbian love affair.

That’s a large amount of content, and the inter-relationships are laid out poetically with movement and music being as important as the dialogue. Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Robbins and Arthur Laurents, the creators of West Side Story, would be happy if they could see this production.

The play was co-created by Paula Vogel (How I Learned to Drive) and Rebecca Taichman, who wrote her dissertation on the topic, and the first version of this play, when she was a student at Yale in the late 1990s. Taichman also directed many Sarah Rule plays and the 2003 Prince Theater production of The Green Violin, a story of Soviet Yiddish theater, starring Raul Esparza.

Indecent relates the history of the drama The God of Vengeance by Sholem Asch, a famed author of short stories. This was his first play, written in 1906, and it aroused discomfort and outrage. It depicted an apparently-devout Jew operating a brothel in the basement of the home he shares with his wife and virginal teenage daughter.

The father commissioned the inscription of a Torah to curry favor from the Jewish community that shunned him because of his business, and to attract a good match for his daughter. While he was trying to buy respectability, his daughter had a lesbian affair with one of his prostitutes downstairs. The father became furious: “This Torah cost all of the whores downstairs on their backs and their knees for a year. Both of you, down into the basement, and take the Torah with you.”

Clearly, the main subject of The God of Vengeance was hypocrisy, and false piety. Lesbian love was a secondary subject, yet notable because its depiction on stage was far ahead of its time.

Asch’s play was denounced for three reasons. One, it showed a pious Jew as despicable; two, it showed a holy Torah about to be hurled to the floor as the curtain falls. (Jews, and not just the orthodox, consider it a disgrace when a Torah or prayer book touches the floor, even when it falls accidentally.) And three, it portrayed a lesbian love affair. Indecent puts primary focus on that lesbian aspect — especially a love scene with two women in the rain. This emphasis is a logical choice when you consider today’s social environment, plus the fact that playwright Vogel is active in lesbian causes.

It does create cognitive dissonance, however, when we get to a scene that shows the Broadway production of 1923 being raided by police. The actors and producer were jailed and fined for presenting something “obscene, indecent, immoral.” But that production used an edited script which omitted the love scene. In other words, the primary objection at that time did not involve that part which has been made the central focus of Indecent.

Still and all, we are swept up in the drama. Parts of Vengeance are re-enacted in Indecent to indicate what all the fuss was about. But the most complete version of the lesbian kiss scene is withheld until the end. It provides a hopeful finale, rather than dwelling on the extinction of the acting troupe.

Comparison with last year’s Shuffle Along, or the Making of the Musical Sensation of 1921 and All That Followed is inevitable. I’m also reminded of a revival I saw of The Captive by Edouard Bourdet, whose cast was arrested for indecency in 1926 because the lead role was that of a lesbian. See link.

Indecent also examines the immigrant experience and the problems of assimilation. Parallels to today’s migration from the Middle East, and from Latin countries to the USA, are obvious. In Indecent, the German actress who starred in the Berlin production complains about the “hordes” of undesirable immigrants “overrunning” her country.

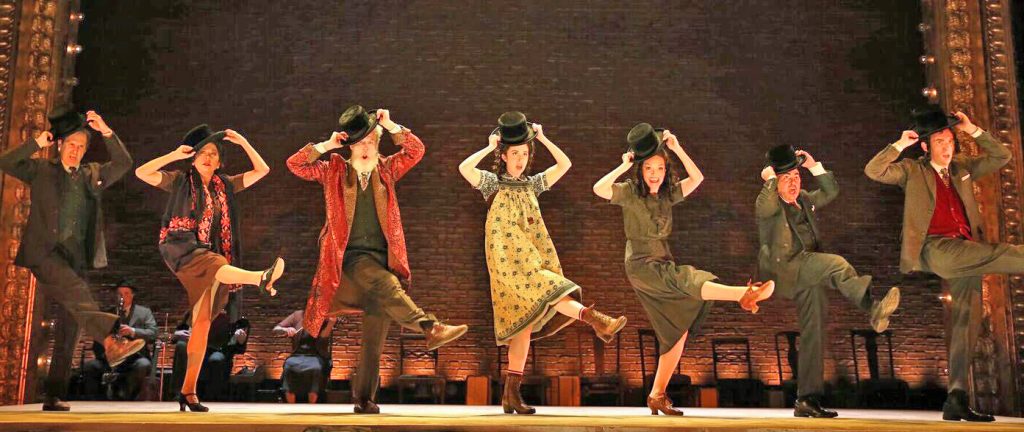

At the time when Asch’s play opened in New York, the U.S. Congress had recently restricted immigration from Europe. Jews were especially targeted, whether they were fleeing Communist Russia or the defeated, financially-devastated Germany and Austria. Many immigrants were rejected and sent back to their homelands. Those who were allowed, adapted. An aging Chassid is stripped of his peyes sideburns; he puts on a top hat, struts in an Americanized chorus line and outkicks everyone. He sings, “What can you do? It’s America. That’s how people look here. Even a Jew looks like a goy!”

The stagecraft of director and co-creator Taichman was impressive. She used innovative presentations of different languages and of “blink in time” stopped motion. A cast of roving players is introduced. When they stretch their limbs it seems as if they haven’t moved in decades. It’s a lost civilization coming back to life. Men lift their arms and dust pours from their sleeves. At the climax of the evening, all these players will go to their deaths in the Holocaust. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

Prior to the anti-Jewish pogroms in Russia in the 1880s, educated Jews looked down on the Yiddish language as a jargon used by the uneducated. Isaac Leib Peretz (1852-1915) led a movement to elevate Yiddish as a respectable language of “neglected beauty,” as the preface to an early publication described it.

Indecent starts in 1906 when Asch read his play for Peretz and the elders of the Jewish community in Warsaw. They rejected it. Peretz, as portrayed here, said that plays should represent Jewish people as admirable, whereas Asch believed that Yiddish theater should reveal all aspects of life.

Rejected at home, Asch brought his play to cosmopolitan Berlin, where we see a cabaret show that’s more bawdy and bisexual than any production of Kander and Ebb’s Cabaret. In that environment, The God of Vengeance was enthusiastically received. Asch’s drama was a success all over Europe. A production in English played in Greenwich Village in 1922. In February 1923 it moved uptown to the Broadway district. Adolph Ochs, publisher of The New York Times, attended a performance and said that the play should be shut down. The ACLU declined to help.

Rabbi Joseph Silverman of Manhattan’s Temple Emanu-El complained: “Yes there are men in our cities who buy their bread on the sweat of these women’s backs. Of these parasites I say: Send them back. I denounce this play.” The judge ruled that “drama must be purified of eastern exoticism, its sexual pollution and its corruptive attitude towards the family.” A jury convicted the cast and producer, although the verdict eventually was overturned.

An additional topic of Indecent is Asch’s distancing himself from his own play. This began as early as 1923 when he washed his hands of the English translation. Asch wasn’t charged with a crime; only the production was, and Asch did not take the stand on behalf of the play. Later, in the Nazi era, he objected to productions of The God of Vengeance because they could inflame anti-Semitism. And after World War II he was concerned about anti-Semitism during America’s anti-communist witch hunts.

Near Indecent’s end we see Asch’s play performed in an attic in the Lodz Ghetto. Then the actors line up to go to their doom. Some of them had been starting careers on Broadway until Vengeance was shut down and disowned, thus impelling them to return to the Poland of their birth, and of their inevitable death.

Students of theater history, like I, perked up when we saw legendary figures impersonated, such as Morris Carnovsky in the 1923 New York scene. I saw Carnovsky as a magnificent King Lear in 1963 at the Stratford Festival, and he also co-starred in Hollywood films. I interviewed him on two of my radio programs and we dined together. It certainly was eerie to see him brought back to life and it accentuated the fact that almost everyone involved in The God of Vengeance is not only dead — but virtually forgotten by the public. Like dust, blown to the winds.

This was an ensemble with musicians and actors performing multiple roles. Richard Topol, Katrina Lenk, Mimi Lieber, Max Gordon Moore, Tom Nelis, Steven Rattazzi, Adina Verson, Matt Darriau, Lisa Gutkin and Aaron Halva all deserve rave notice, as does David Dorfman for his choreography. Nelis, who took over as the male lead in The Visit last year, was especially eloquent with his outstandingly graceful movements while portraying elderly men. That’s him below, with the white beard.

See video here.