“All I’m asking for is a tune/

Something itchy to tap my toes to…/

I’ll tell you why I love to make music:/

I feel like I belong.”

That’s William Finn expressing his love affair with music. It’s part of his lyric for “Mister Make Me a Song,” which was issued by RCA on an album called Infinite Joy: The Songs of William Finn. This live recording was made during two evenings of cabaret at Joe’s Pub at New York’s Public Theater in 2001. It included songs from five Finn shows and personal numbers, some of them sung by Finn himself, and it makes a great starting point for examining his career.

“People who know me well think that the title is not appropriate for one of my shows,” says Finn. “Rather, they say, call it desiccated joy or circumscribed joy or itty-bitty joy.” He refers to his reputation for complaining. “But what gives me unending pleasure, infinite joy, is a well-made song, and I’ve written some well-made songs. That may sound like I’m bragging, but I don’t care.”

Finn won two 1992 Tony Awards for the best score and best book on Broadway for his musical, Falsettos, and his 1998 show, A New Brain — staged at too small a house to be eligible for a Tony — was equally good.

The song “Infinite Joy” was written after the death of his mother, Barbara Cohen Finn, in 1998. “A wonderful woman. One of the most positive people I ever met.” Admitting that he’s gone through angry, depressed periods, Finn says his mother was different: “She thought that being depressed was a wasteful luxury. She was enormously supportive.”

Barbara was an attractive blonde woman of 69 when I saw her at a workshop of A New Brain in 1997, the year before the show premiered at Lincoln Center. She was suffering from pulmonary fibrosis, but was happy to be seeing her son’s work — especially because it was a play written after Bill Finn recovered from brain surgery and was about a composer who survived a similar crisis. The composer’s mother in A New Brain is based on Barbara, and she enjoyed seeing and hearing this tribute.

As we parted that afternoon she told me and my wife, and everyone else who was around, that she looked forward to seeing us at the opening. We didn’t realize that her heart was becoming progressively worse, and a transplant was denied her because healthcare officials think that new hearts shouldn’t be given to people as old as 69.

As opening night approached it became clear that Barbara couldn’t travel to New York for it. She didn’t want extraordinary measures to prolong her life, and Bill says he got the impression that she had made a deal with God when her son was critically ill, to exchange her longevity for his. Bill went back to Massachusetts to be with her, and, on a Sunday late in May, as he wrote in another song, “In a very quiet way, the earth stopped turning.”

“Infinite Joy” celebrates Barbara’s effect on his life. “I see the world through your eyes, and possibilities arise…You said that life has infinite joys.” It was sung at Joe’s Pub by Liz Callaway on a Sunday night and by Norm Lewis the following evening. Both of their renditions are on the RCA CD. While “Infinite Joy” is a fine song, “The Day the Earth Stopped Turning” is even better: a great song with poetic lyrics, sung by Carolee Carmello. Its haunting minor chords are unlike anything he wrote before. The songwriter paraphrases Barbara:

“Now throw away your hate/

And focus on what’s great instead./

I’m dying, so there’s no time for debate…”

In the middle of the song, Finn makes a surprising shift from second person — using the word you — to third person — she — and from present to past tense as his story moves from the past to the present. What may seem like a strange confusion of time actually comes across as a reminder of how the past is still with us.

“The world is good, she said./

Enjoy its shit, she said, /

‘Cause this is it, she said./

So make a parade of every moment./

Now pull up to the curb; The sign Do Not Disturb’s ahead./

The truth is that you made my life superb, she said.”

The imagery of Do Not Disturb to signify death is arresting. It’s hard to find a lyric with such a concise conclusion to a story of life and death.

Born in 1952, Bill Finn grew up in Natick, Massachusetts. Though the last name may sound Irish, Finn was the name given to his Jewish grandfather when he came to the USA. As a child, Billy would dance around his family’s living room to the music of Guys and Dolls. (The show was written before Finn was born but the movie version was released when Bill was three, so apparently that’s when his dancing started.) “I used to do that, which is a frightening, frightening thing. I was always interested in the theater and just gravitated there. And I was always smart, so my parents figured I wasn’t doing anything stupid and they were supportive. I must have been an obnoxious child, always singing and always — well, dancing is not the word. Moving is more accurate.” When Bill was eight, Bye Bye Birdie premiered and became his new favorite show.

Bill’s parents, Jason and Barbara Finn, never gave him — or his sister and brother — music lessons. When he got a guitar for his bar mitzvah, Bill taught himself to play and hung out with friends singing and playing folk music and making up his own songs. The singer-songwriters he most admired were Joni Mitchell and Simon and Garfunkel. During high school, Bill taught himself piano and gave up guitar. He was never interested in rock. “Try as I might, there’s nothing rock about me.”

His father had a gambling problem, just as the father character in A New Brain. His parents fought a lot (“we also laughed a lot”) then divorced when Bill was in college. Finn majored in English Literature at Williams and performed in the school show in his freshman year. When he improvised new material “I made everything funny.” He so impressed the other students that they asked him to write music and lyrics for the next show. At first, Bill resisted the assignment because he didn’t know notation. But he found a way to teach others his songs. And he found what he most enjoyed in life.

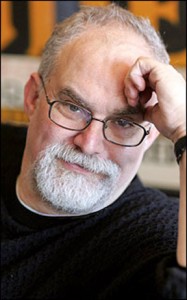

Six foot three, black-bearded and imposingly handsome, Bill loved to perform but had no opportunities. After graduation, he had various odd jobs. “I wrote for an airlines magazine, and I was a bartender — a very slow, bad bartender,” he told us. He did in fact hitch-hike across America, as in his song with that title. It has a happy, swinging tune which Lewis Cleale belted out at the Joe’s Pub concert.

Six foot three, black-bearded and imposingly handsome, Bill loved to perform but had no opportunities. After graduation, he had various odd jobs. “I wrote for an airlines magazine, and I was a bartender — a very slow, bad bartender,” he told us. He did in fact hitch-hike across America, as in his song with that title. It has a happy, swinging tune which Lewis Cleale belted out at the Joe’s Pub concert.

“I like that number. It starts as a story song and ends as a love song,” Finn boasts. He cautions that his first-person songs can’t be taken as literally autobiographical. “I write from a very personal place. My songs are emotionally true but not biographically true.” For example, unlike the lyric in the song “Republicans,” he never went to bed with a Republican. His lyric says: “To be screwing a Republican is damn unappealing, but I can’t help the feeling that it’s nice to have the roles reversed.” In real life, he prefers to not associate with Republicans and says he would never go to bed with one.

Many theater-goers assume that the character of Marvin in Falsettos is Finn, while, actually, he based it only loosely on his own life. Situations in his plays are not exactly true to life. For instance, unlike Marvin, Bill was not married before he discovered he was gay. Another example is in A New Brain. The fictitious Gordon Schwinn is an unsuccessful songwriter toiling for a kids’ television show. But the real William Finn was basking in the critical and financial success of Falsettos when he became ill. Also, Schwinn collapses over a platter of ziti in a restaurant. In real life, Finn collapsed on the sidewalk outside an Italian restaurant. Despite all that, the personalities of Finn’s characters are much like his own.

Finn says that his early songs were simpler and not as good as what he wrote later: “My early stuff was presentational, Brechtian. When I began to get personal, my songs got better. I like to write songs that tell you the story of a life in 3 or 4 minutes, where a panoply of emotions is expressed, and also where real craft is demonstrated.”

In 1978 when he wrote In Trousers, subtitled “The Marvin Songs,” about a neurotic, funny, gay Jewish man named Marvin, Bill played the role himself. Most of the songs in that show are for Marvin. He dominates the show — narrating, describing his actions in the third person, and moving back and forth between adulthood and himself as a 14-year-old.

“Three friends of mine who are singers – Mary Testa, Kay Pesek, Alison Fraser – and I performed the music four times in my apartment. We borrowed chairs from the temple across the street, served grapes and got offers,” says Finn. “The show took off, and as it got bigger I had to choose between performing and directing it, and I surprised people by choosing to direct.” Chip Zien became Marvin for a Playwrights Horizons production in 1979. In Trousers has an original cast recording. Mary Testa was even stronger and more soulful at Joe’s Pub in 2001 than she was in 1979, when she sang “Set Those Sails.” Stephen DeRosa led the hilarious “How Marvin Eats His Breakfast.” Zien sounds properly disturbed and angry in the 1979 recording, while the 2001 DeRosa is more playful.

Michael Starobin was the pianist for In Trousers and, when the show expanded, he orchestrated it and conducted the band: “We rehearsed starting at midnight upstairs from Playwrights Horizons and afterwards, in the wee hours, we’d go to an all-night diner on Eleventh Avenue and hang out with all the transvestites. We used a 12-piece band, made up of our friends, in a 50 seat theater. Bill said he was the best Marvin? Oh, he’s so full of humility. Actually, his voice then was sweet and reminded some people of Randy Newman. Then he damaged it by singing when he shouldn’t have.”

Starobin worked on almost every Finn show since, and he sheds some light on Finn’s working methods: “He’s not a trained musician but he plays the piano well and he has his own way of writing down the notes on yellow legal pads. He painstakingly works out the melody and the accompaniment. Above the words he writes which notes he wants, A# or B or C. Then I used to bring my tape recorder over to his apartment and record him playing and singing each number.

“He knows exactly what he wants. When he played a song from In Trousers — ‘Nausea Before the Game’ — it had a very tricky rhythm, the most quirky piece I’ve ever heard. I notated it as 12/8 time, which is unusual in itself, and Billy said ‘No. This isn’t what I want.’ He actually wanted something that doesn’t exist – 11-and-a-half/8 time. He makes his own rules, his own music.”

Finn impressed critics in 1981 when his March of the Falsettos made its debut at Playwrights Horizons. In it, the Marvin whom we met in In Trousers leaves his wife for another man, and has to deal with the confusion that it causes in his ten-year-old son. “I played Marvin in the first reading of March of the Falsettos,” says Finn. “That’s the last acting I did.” Frank Rich wrote of the show in The New York Times: “The songs are so fresh that the show is only a few bars old before one feels an unmistakable, revivifying charge of pure talent.”

Finn’s music was distinctive in the way he combined word play, metric surprises and unpredictable line-lengths with direct, emotional melody. His subject matter was revolutionary. For the first time, a musical-theater songwriter wrote about gays and about contemporary Jews — not just long ago and faraway Jews as in Fiddler and even the more-recently-set Milk and Honey, but urban American Jews of today. In addition, they were Jews with Jewish lives, like Finn himself, wrestling with the meaning of bar mitzvah and the existence of God. It’s odd, with so many Jewish songwriters around, but no one else writes musicals about contemporary American-Jewish family life.

In his 2001 play Magda Lazlo, Arthur Laurents had his ingenue stress that she isn’t Jewish, she’s a Jew. Well, Bill Finn makes it clear that he isn’t just a Jew, he’s Jewish. “I like being Jewish, and I celebrate it in my work.”

Nine years later, Finn continued the story of Marvin and his extended family in the one-act Falsettoland, and then it was combined with March of the Falsettos to make the two-act Broadway hit Falsettos in 1991.

A show originally called America Kicks Up Its Heels occupied Finn’s attention through most of the 1980s. It was a vaudeville about Jews during the Great Depression at Playwrights Horizons in 1983. Then it was re-done with black characters as Romance in Hard Times at the Public Theatre in 1989. It closed after only six performances. Some reviewers called it “whimsical” or “wacky” and complimented its “charming buoyancy and deliberate silliness.” David Barbour in The Bergen Record praised its “exciting, eclectic blend of swing, gospel and pop sounds.” Leida Snow on WINS radio described the score as an uneasy mixture of Three Penny Opera, Dream Girls and Porgy and Bess. Michael Feingold in New York called it “the worst wonderful musical — or perhaps I mean the best idiotic musical — I’ve seen in years…something like a Road Runner cartoon with a screenplay by Victor Hugo.”

Some of Bill’s friends say that its music is Finn’s masterpiece and refer to the show as “pure Finn,” meaning without Lapine. Finn understands: “A friend of mine, a Polish avant garde movie director named Bolek Greczynski, told me that Romance in Hard Times was great, but Falsettos was bourgeois shit. Romance was a very out, very avant garde celebration of life.”

Lillias White told Playbill On Line “One of my favorite parts was in Romance in Hard Times. It takes place during the depression and was very zany. I played a woman who had conceived a baby and decides to hold it inside her body until the world is a better place. The music was brilliant, brilliant, brilliant. Every time I talk to Billy I say, “Let’s do this one again.”

Mary Testa sang “All Fall Down” from America Kicks Up Its Heels/Romance in Hard Times on the CD, the lament of a woman whose husband left her, which Finn taught her for a club appearance in 1982, before the show opened. Its mood is the flip side of the wife’s comic lament in Falsettos, “I’m Breaking Down.” Testa’s abandoned wife is angry, unaccepting, and doesn’t see any humor in the situation, and Finn’s music is turbulent, even violent.

Starobin says that Finn wrote “three or four scores worth of songs” for America Kicks Up Its Heels and Romance in Hard Times. But finding all the music he wrote would be difficult, says Finn. “When a show closes I get so depressed I say to hell with it and I throw things away.”

That action sounds familiar. People who saw A New Brain will remember that the songwriter’s mother, trying to keep busy while her son lay dying in a hospital, cleaned his room and threw out his books. Barbara Finn told us, at a reading of A New Brain, that she really did throw a bunch of Bill’s books away.

André Bishop, artistic director of Lincoln Center, says that the score of Romance in Hard Times must be recorded, but Finn resists the idea. He thinks the public wouldn’t understand what’s going on, and says the show should be re-written: “It needs to be Lapinized, structured. That’s what Lapine does for my shows, he pulls them together and structures them.”

Lapine explains: “My strong suit is structure. That’s what I bring to the table. I contribute to storyline and character. I give him feedback and sometimes ask him to write a new song. But he writes all the words and music.” Finn adds: “One other thing that Lapine does for me is get me unstuck. He’s a wonderful writer, and he has an unbelievably fertile mind, so that when I sit and whine ‘I don’t know what to do,’ he goes ‘Well, what about this, or what about that’ or ‘Make him a frog’ [referring to a character that was added to A New Brain] or something. So it’s a way to get unstuck.”

Those who appreciate what Lapine does, and those who don’t, both can find examples in A New Brain to bolster their case. First, the good. In early workshops, the composer Schwinn complained about his employer, who is the host of a kids TV show, but we never met the man. Later in the creative process, Lapine suggested making him appear in a TV frog outfit, personifying Schwinn’s fear. And Finn added a song for that character which Schwinn hears in his mind as he wakes from surgery, a song that tells him “Don’t Give In” and indicates the songwriter has turned the corner mentally and physically. These changes add an extra dimension to the show.

On the minus side, Lapine asked Finn to cut an early scene which revealed the loving relationship between the songwriter and his friend Roger. In playful bedroom banter, the two men talked about sex and eating cookies, and then Roger sang the beautiful “Sailing.” Showing the songwriter’s love of eating, this scene prepared us for two later songs about his problem with weight.

“Sailing” (“I’d rather be sailing and then come home to you”) was sung affectionately in that scene of the composer in bed with his lover. But when the show premiered, the song was re-positioned and the lover, alone, made his entrance with it. In that context, “Sailing” lost some of its romantic impact. If someone, someday records Finn’s work complete and uncut, the way classical labels do Mozart or Mahler, I’d like to hear the excised scene restored. In its original version, “Sailing” had a gorgeous verse and an extended ending.

Lapine asked Finn to edit A New Brain for concert performances which he directed in New York in 2015, and this provides another example of Lapinizing. What he wanted deleted were two songs of Schwinn hallucinating while in a coma after his brain surgery. Those songs showed the hero projecting his own worst qualities onto others: “Eating myself up alive” and “In my dreams I’m always up and walking, self-assured…but when I wake it’s gone.” This was the wild and angry Finn of his earlier shows, pre-Lapine.

Another song in A New Brain recalls the Finn of Romance in Hard Times, as a homeless woman sings “Change the government, change the system…We live in perilous times.”

“Anytime” was written for the funeral of a friend of Bill’s, Monica Feinstein, and later was put (temporarily) into A New Brain. The lyrics are from the perspective of a person who might be dying, so it was assigned to Malcolm Gets, as Schwinn, and he sang over a loudspeaker as he was wheeled into surgery. Clearly the loudspeaker idea didn’t allow the song to be heard properly, and the number was removed from the production. Producer André Bishop says now that “Anytime” was cut “because it caused the show to emotionally peak too early.” Bishop admits that “one has to wonder what anyone was thinking of” when it was cut, while Finn complains that it was excised against his wishes while he was out of town attending to his mother. The ballad was sung gorgeously by Norm Lewis on the Joe’s Pub CD.

“Anytime” is a parent telling his or her child that he/she’ll always be there, “anytime you laugh, anytime you cry…I’ll be there on the baseball field, though I’m well concealed I’ll be out there cheering…I’ll be there in the maple trees on a summer breeze on a perfect evening…and I’m watching it all, yes, I’m watching it all.” Notice how he/she switches to the present tense. Even after death, he or she remains: “I am there each morning, I am there each Fall, I’m watching it all…Be aware, I am there.” What a message to leave behind!

Discussions of A New Brain usually say that the play is about brain surgery. But, to me, the show is about creative frustration, and all the songs we never get to write — whether it be because of illness or emotional blocks or procrastination. Because this theme is universal, and because the score has so much richness and variety, the show deserves a bright future. Finn says it is his favorite. Although I was moved by a two-piano performance of it (with Ted Sperling and Seth Rudetsky) and Starobin’s seven-piece orchestration is lovely – piano, synthesizer, drum, woodwind, violin, cello, French horn – Finn imagined it with a big orchestra and in a larger theater. He complained when it was booked into the smaller of Lincoln Center’s two spaces.

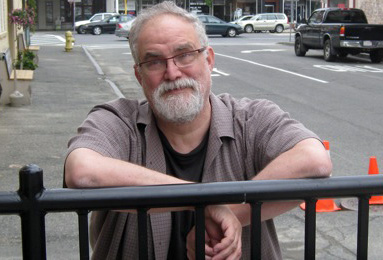

Friends say that Finn complains about a lot of things. He is depressed because he has no new show on the boards. Falsettos and The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee made money, but these days there are few professional, royalty-producing productions. “I need more money,” he says, “and I don’t mind you quoting me. I have enough to live on, but I want money to buy gifts for friends and family members. Until now, I’ve never cared about money and I’ve made all the wrong career choices for making money.”

Finn was involved with The Royal Family of Broadway since 1998 and the delays made him unhappy. He enjoyed writing songs for it, but was mystified by some of director Tommy Tune’s casting ideas. For example, Julie Harris was Tune’s choice for the female lead, the part based on Ethel Barrymore. “Didn’t anyone wonder why Harris never made her career in musicals? I told Tommy that maybe the part didn’t require a great voice, but she had to hit the notes and she wasn’t doing that, and he just said ‘There goes Mister Negativity again.’ He always called me Mister Negativity.”

Finn stayed with the project mainly because he was pleased with the song he wrote for the leading lady:

“Reading papers when there ain’t a review/ Is a stupid thing and I won’t do it.”

When Finn writes lines like these, you wonder if it’s the character or himself:

“Living life like a normal person/ A stupid thing; I won’t do it…”

“I live with passion, joy and rage/

The only time I feel alive is when I’m on the stage.”

I talked with the producer, Barry Weissler, who had put Falsettos on Broadway, about his hiring of Finn for The Royal Family. “I know the play isn’t about gays and no one’s dying,” said Weissler. “The play is about a theatrical family. But think about it. Theatrical people are outside the mainstream of society. They are people who express themselves at a higher pitch than most of us, and no one writes better from that perspective than Finn. He’s the perfect person to write for these characters.” Lapine thinks Finn was a good choice for the assignment “because he has such a love of the theater, and because he writes great women’s roles, and this play calls for that.”

Tommy Tune dropped out of The Royal Family. Jerry Zaks came in to direct and Richard Greenberg to write a new version of the book. Greenberg, like Finn, is an outsider with a quirky view of life. His 1998 play Hurrah At Last took a surreal look at a hospitalized writer, somewhat similar to Finn’s protagonist in A New Brain. But after a workshop reading of The Royal Family, people in control of the rights wanted a less-wacky, more literal story line, a more traditional musical play. So Lapine was brought in to rewrite and give it that tone. It still has not been produced.

The recording producer for Infinite Joy was Jay David Saks: “I never properly appreciated Finn’s work until I saw this review and heard the old and new songs that’re in it. I was blown away. Brilliant, quirky, bizarre, interesting. His songs are emotional, heart-on-sleeve. But Bill never seems to know if people appreciate his music. He often asks: `Did you like my song?’”

“Billy worries about his work and whether it’s being treated well,” says Starobin. “In the past, his dark moods were because of career frustrations. He struggled for ten years on one show, Romance in Hard Times, and then the critics didn’t like it. There was anger that he wasn’t recognized, like the angst of Marvin. But unlike Marvin, this doesn’t dominate his life. In his personal relationships, he’s happy and fun to be with. He’s so charming. He makes you laugh.”

Finn was been cured of the venal malformation in his brain and is in excellent health. In the past, Finn has been a big eater, but now he looks trim. And he’s celebrating more than 25 years in a monogamous relationship with New York businessman Arthur Salvadore.

Another Finn song is “The Ballad of Jack Eric Williams,” a eulogy for a dead, unsung songwriter who lamented that his music “isn’t exactly the fashion of the day.” Finn’s lyric about Williams resonates with me because I remember Finn saying that the world had passed him by, that dreck by other writers was being produced while his work wasn’t.

When Intimate Joy was performed at Joe’s Pub he was in a sunnier mood. How could he not be, when he saw how the room was packed and how every song received cheers. “Yes, people love me,” he said to me. “A little.”

Please share your thoughts with us. Address to editor@theculturalcritic.com

And read other reviews on The Cultural Critic

For stories about other Broadway songwriters, click here.