Glass Handel, a world premiere production, part of Festival O18 by Opera Philadelphia at the Barnes Foundation. Music of George Frideric Handel & of Philip Glass.

Glass Handel is a three-ring circus, and then some. Four-ring is more accurate. The production presents the countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo singing in front of two orchestras and alongside ballet dancers to his right, while an artist creates acrylic paintings on a back-lit screen to Costanzo’s left, with film interpretations of the music displayed beyond that.

As if all this isn’t enough, the audience is thrust into the action as well. It seems overwhelming — perhaps even pretentious — but it works amazingly well. This is an evening of sensory sensations surrounding a basic theme, and it’s the highlight of the O18 Festival.

Costanzo is known for his performances in Handel operas as well as George Benjamin’s Written on Skin and Prince Orlofsky in Strauss’s Fledermaus. He recorded a program of arias by Handel and Glass that’s just been released on the Decca label and he conceived this multimedia production built around that program. He engaged luminaries from the worlds of art, fashion, dance, and film to create a new way to experience live music. The venue of the Barnes Foundation is appropriate because Albert Barnes made a point of displaying paintings alongside furniture, utensils and pottery as part of a unified experience, and he even presented classical music.

I arrived early and chose a seat in the second row of the Barnes long rectangular entrance hall, directly in front of the two orchestras and a platform where the singer would appear. Yet it soon became noticeable that supers pushing dollies were methodically lifting the chairs of audience members and wheeling them to new locations. As my neighbors were carted away, I braced myself for what I thought would be a disruption. My fear was needless.

The people-moving was done smoothly and I was slowly transported to the area directly adjacent to the stage where dancers Patricia Delgado, David Hallberg and Ricky Ubeda took turns executing the choreography of Justin Peck, the esteemed 31-year-old head of New York City Ballet who also staged the dances of the current Broadway revival of Carousel. Their balletic interpretations of the music were viscerally exciting, although restrained by the small dimensions of their stage. Seeing their bodies close-up was a worthwhile experience that would be impossible if I stayed put in my original spot.

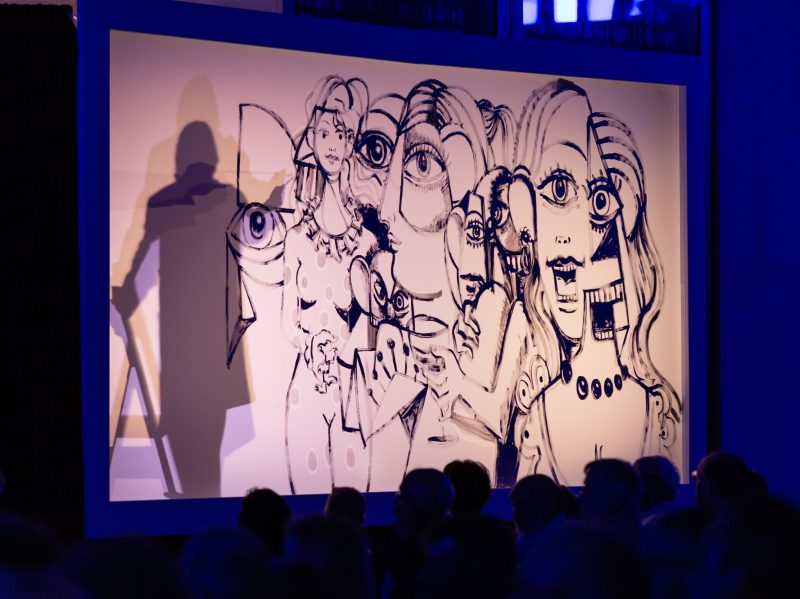

Even from this new location I could see and hear Costanzo. Later I was again moved to a location in front of the screen where artist George Condo was visible in silhouette as he used his brushes to create a large black acrylic painting in a style resembling Picasso’s cubist period, supposedly inspired by what Costanzo was singing. He is doing a different painting each night and plans to display the entire series in a gallery show.

Those vehicles that lifted our chairs and transported us around are explained by Costanzo: “When listening to Glass or Handel, I experience the music deeply when in motion — biking around a city or sitting on a train. I had this idea that somehow we could get the audience in motion. Ryan McNamara, a performance artist, came up with a system for moving people in their chairs around a space during performance. People would move around without leaving their chairs, and they would encounter different ‘stations,’ each an embodiment of the live music in a different discipline.” I agree with him that they give each audience member a unique immersion.

Simultaneously, a dramatic movie by the famed filmmaker James Ivory accompanied the Handel aria “Stille Amare.” We saw Costanzo in medieval costume wading across a river and confronting an armor-coated man on horseback. Then dancer Ron Myles gave a beautiful performance in the film of Glass’s “Liquid Days” directed by Mark Romanek. Another of the filmed interpretations is a surrealistic, colorful abstract by Mickalene Thomas for Glass’s “The Encounter.”

Central to all of this is the set of nine vocals sung by Costanzo, alternating between the composers. He has a haunting alto voice with rare intensity that takes on masculine chest timbre in dramatic lower passages. This variety of color sets him above other countertenors. His technique is impeccable and he adds considerable power to the austere Glass selections. The composer sanctioned re-scoring of his minimalist music in selections from Monsters of Grace, 1000 Airplanes on the Roof, Fall of the House of Usher and Akhnaten. In particular, the closing number from 1000 Airplanes makes an exciting climax as the dancers join Costanzo on the center stage.

Costanzo appeared first in a billowing red dress designed by Raf Simons for Calvin Klein. Later he changed to a blue satin ball gown, then a white and black shift. Even the instrumentalists and the chair-movers wore accessories by the costumer. (Costanzo will be taking on the lead of Glass’s Akhnaten at the Metropolitan Opera in 2019.)

Corrado Rovaris led two chamber orchestras, side by side, one for each composer. The Handel ensemble of 20 included theorbo and harpsichord. The Glass orchestra of 34 included lute and seven brass that weren’t in the Handel group. Rovaris could have conducted a single orchestra with certain players used only for individual numbers of course, but this choice added to the visual pizzaz of the enterprise. It was a welcome part of a creatively extravagant evening.

This review originally appeared on the international website The Opera Critic.

Below, artist George Condo at work.