Golden Cockerel (Coq d’Or) by Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov. New Opera NYC at the Loreto Theater, Sheen Center for Thought & Culture, New York, May 2017.

Golden Cockerel (Coq d’Or) is a musical fantasy, composed by Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov in 1907 with splashy orchestral colors reminiscent of his Scheherazade. The subject matter surprised me with its relevance to contemporary politics.

Rimsky-Korsakov and his librettist, Vladimir Belsky, had a political agenda, and they based the opera on a poem by an earlier Russian who also was politically motivated.

Alexander Pushkin lived in a time with no freedom of speech, so he disguised liberal anti-czarist political messages in the form of fairy tales. In 1825 Pushkin’s poems were linked to the unsuccessful Decembrist Revolt against Czar Nicholas I. Some of Pushkin’s friends were executed, others exiled to Siberia, and he was banished from St. Petersburg to the Caucasus mountains. After that, he wrote Golden Cockerel. He died in a duel at the age of 37.

Pushkin was inspired by Washington Irving’s 1832 story The Alhambra about a Moorish king who built towers on his borders to keep foreigners out, and who made a bargain with an astrologer and failed to honor it, whereupon the astrologer seized what he desired and disappeared into a subterranean world.

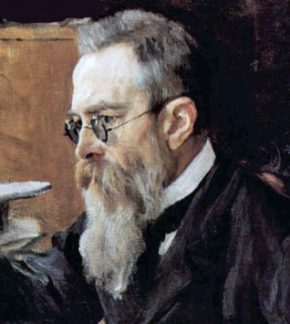

Rimsky-Korsakov had been an officer in the Imperial Russian Navy, and was famed for his Russian nationalism, expressed musically with alluring melodies. He wrote Scheherazade, Russian Easter Overture, and The Flight of the Bumblebee, and he completed Mussorgsky’s Boris Gudunov and Borodin’s Prince Igor.

In January of 1905, thousands demonstrated in Saint Petersburg for voting rights and better working conditions, and many of them were shot dead by czarist troops, while sailors mutinied against their officers at the port of Odessa. (This became the basis of Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 film Battleship Potemkin.) Rimsky-Korsakov supported these protests and therefore was dismissed from his position as head of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory.

The czar told his supporters that he would “bring order back to Russia” but granted only limited reforms, and revolutionary protests increased. Labor unions (Soviets) became the main agitators, eventually bringing on the fall of the empire in 1917.

Golden Cockerel had its premiere in 1909, after Rimsky’s death. It is a satire of the autocracy, of Russian imperialism, and of the Russo-Japanese war which was started by Czar Nicholas II and ended in disaster. This production was designed and directed by Igor Konyukhov, founder of New Opera NYC, a Russian born PhD in nuclear physics who has become a director and choreographer.

The costumes combine 1960s psychedelia with the primitive oriental look which Rimsky and librettist Belsky associated with czarist Russia. Day-Glo luminescent colors predominate. Rimsky would have enjoyed seeing the hippie attire of this production; he himself chose to wear blue-tinted, wire-rimmed glasses, even when he was in his 60s.

The solo trumpet fanfare that opens the opera is thrilling; it’s one of the most distinctive of all brass solos. This leads into an orchestral score filled with exoticism. J. David Jackson, who has conducted Russian opera in major houses, including Prokofiev’s War and Peace at the Met, vividly led a 36-piece orchestra.

King (or Czar) Dodon thinks that evil enemies “from the East” are threatening his kingdom, so he orders a pre-emptive war. His attack ends in disaster and his two sons, who led his army, stab each other to death. Dodon then takes personal command, and he chooses to pull back his troops and defend the homeland. Ksenia Antonova as the Golden Cockerel perches herself in a tree and scans the horizon with binoculars, looking for invading armies.

In Act II, Dodon is confronted by Shemakha, queen of the enemy nation. Appearing with blue skin, set off by bright orange lips and eye liner, she sings a languorous Hymn to the Sun. Alexandra Batsios was sensuous, wearing a colorful gown and veils. She leads Dodon into his own dance, a comic travesty. Shemakha tells Dodon that he looks like a camel or a hopping turkey, but eventually the two of them connect romantically.

At the wedding ceremony, the Astrologer asks Dodon to make good on his “campaign promise” to grant any wish of the Astrologer. “I want the Queen of Shemakha” says the Astrologer. Dodon furiously kills him with a blow from his mace. The Golden Cockerel, defending its master, swoops down and severs Dodon’s jugular vein.

The cast sing about the dawn of a “new day” — apparently happy to see the czar overthrown. But then they ask plaintively, “How will we live without the czar?” Pushkin apparently was prescient about what was to happen in the Soviet Union. This uncertainty about Russia’s future had been expressed in earlier Russian operas, most notably in Boris Gudonov. Perhaps Pushkin (or librettist Belsky) had intuition about the Bolshevik and Communist reigns, and the Stalinist dictatorship, that were to come. The possibility prompts serious thought at the end of this otherwise-comical opera.

At the Met in the 1930s and 1940s, the lead roles of King Dodon and Queen Shemakha were usually sung by Ezio Pinza and Lily Pons. At New York City Opera in the 1960s they were a specialty of Norman Treigle and Beverly Sills. Mikhail Svetlov, from the Bolshoi, made a tour de force of his role. He has a commanding bass voice and great stage presence. In the performance I attended, Alexandra Batsios was more dramatic than the chirpy Zerbinetta-like voices of the past. She had a rich sound and also commanded the high E (above high C) that caps her aria. Julia Lima alternated with Batsios as the queen.

The part of the Astrologer is written for a voice called “tenor altino” — a very high lyric which shifts into falsetto. John Villemaire made the part strangely appealing. Ksenia Berestovskaya displayed a major mezzo voice as Amelfa, the cook, with fruit and flowers atop her head. This is a role once sung at the Met by Margaret Harshaw. The title role is a featured spot, not really a lead role, and Ksenia Antonova competently handled its high coloratura.

These performances were in Russian, with English titles. The Met used to do it in French, and New York City Opera sang it in English.

Below, Batsios & Svetlov, photo by Steven Pisano, and below that, Batsios in a Sarasota production of Golden Cockerel: