“All right, everyone. Get ready. We’re going to do some wild things” says Jay David Saks to the crew assembled in the control room at The Hit Factory.

Despite what it sounds like, he’s not about to start an orgy. Nor is he about to re-record the Jimi Hendrix song of similar name. No. “Wild things” is the professional lingo for detached sounds that are recorded, out of sequence, to be inserted later, at various points in an album. Sounds such as tap-dancing steps, finger snaps, or laughter. They are like wild cards in poker—the jokers and one-eyed jacks that can be stuck into a hand to fill out a flush or a straight. Similarly, wild stuff gives a producer the chance to enhance his recordings.

On his CD of the show Marie Christine, the sound of kids’ laughter let us know that Marie’s two children were present in a scene, even though they had no spoken or singing lines. On Fosse, tap sounds and finger snaps remind the listener that this was a hoofer’s show. On Cabaret, tinkling glasses and laughter cue us that we’re sitting at tables inside a nightclub.

Saks records these sound bites at a time when most of the musicians and singers aren’t around, in order to control costs. You record chorus numbers when everybody’s there, then you do solo songs after the chorus members have punched their time clocks and departed. Then do the wild things after the band has left the building. All of this is carefully pre-planned, and it’s part of the job for Saks, who is among the most-honored of record producers and who also is in charge of sound for Metropolitan Opera broadcasts and telecasts and PBS concerts from Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center.

On the day I first saw Saks do his wild thing, he was supervising the CD of Fosse, which had just opened on Broadway in 1998. Looking, literally, over his shoulder, I got to see how he runs a recording session. The locale was The Hit Factory, a building on Manhattan’s West 54th Street whose hallways are lined with framed gold records that have been created there. The session was scheduled for the first Monday after the opening night, because that’s the one day of the week when no performances take place on Broadway. But the producer’s work begins way before then.

“I go through the score and attend performances, read the script and listen to recordings made in the theater. I decide what music to include and how to edit it. Things that work in the theater might not sound clear on records. We have to use some dialogue to make the story clear. Cut some long dance sections. I collaborate with the author, composer, director and conductor. We have lots to discuss in production meetings in advance.” He also has to choose the types of microphones and where they will be placed.

On this Monday afternoon, Saks sits in the middle of a control room filled with 12 large consoles. He has dark brown hair and wears narrow gold specs, pushed halfway down his nose. Although it is January, Saks wears an open-collar short-sleeve polo shirt. A watch with a wide black band is on his right wrist. To his left sits the chief engineer, wearing a red baseball cap, mustard-color jersey and sneakers. He slides left and right in his wheeled chair to adjust sliding volume switches. Other engineers are at their consoles. On Saks’ right sits the show’s director, Richard Maltby, Jr., graying, with big glasses, wearing a black velour pullover sweater. On a couch behind Saks are this writer and Ann Reinking, Fosse’s one-time lover, the star of the revival of his Chicago and caretaker of the Fosse legacy. She is in a black pants suit with a brown and yellow scarf. Button-nosed, with long straight reddish hair, she chews on the temple of her wire rim specs.

On the other side of a glass wall are the conductor, orchestra and singers. When they swing into “Bye Bye Blackbird,” Saks, Maltby and the engineers tap their feet and sway their bodies. The only person in the room who isn’t moving—oddly—is the dancer. Reinking sits quietly, reading a paperback novel. Much of the time, Saks is on his feet, strolling around, eyes down, looking at the score. He stops the musicians occasionally to make comments like: “Why does the trumpet hold onto that last note?” or “Valarie, you sound great.” Often he turns to Reinking for her reaction. Once she says: “They should sing that part softer; I’ll go tell them,” and she walks into the studio to deliver her instruction personally. Her role seems primarily to be liaison between Saks and the cast.

Sometimes Saks makes changes based on what he’s hearing: “On page 40, on the downbeat, Valarie [Pettiford] doesn’t have time to sing her line,” and he asks the conductor to count an extra beat. Every hour, there’s a mandated ten-minute break—like a psychiatrist’s schedule—when everyone goes into an adjoining room for food and drink. A large table groans under the weight of tray upon tray of smoked fish, cheeses, fruits and cakes. One of the engineers complains, as he wipes his mouth: “This is my third recording session this month. I’ve gained ten pounds!”

After the recording sessions, Saks hardest work begins, in relative solitude. “I spend three days choosing the best moments. We decide who makes it into the life raft and who doesn’t. In other words, what songs have to be cut so the show will fit on a CD. Occasionally we bring a singer back to re-record some passages if he or she wasn’t in the best voice the first day. Then I spend a week mixing to get the right sound and ambience. Several more days deciding sequences, creating overlaps and assembling everything. Then we bring in the song writers, director and musical director to get their approval.” Sometimes he’ll hear a negative reaction. More about that in a moment.

Born in New York City in 1945, Saks studied violin and went to Juilliard Preparatory School. There he switched to piano as his principal instrument. His parents suggested pre-med, but, instead, he majored in orchestral conducting and composition at Mannes College of Music in New York. When he graduated in 1970, his classmate Murray Perahia told Jay that he should consider a career in record producing. So, while Perahia become a concert soloist and signed a contract with Columbia Masterworks in 1972, Saks got a job that same year as a producer at Columbia. “I worked under the two Toms,” Saks relates, referring to Thomas Frost, who specialized in classical, and Thomas Z. Shepard, who did classics and Broadway.

In those days, Saks didn’t attend Broadway shows. “Tom Shepard asked me to assist him on A Little Night Music and said he’d show me what to do. I wound up editing and mixing the tapes.” Editing at that time consisted of using a razor blade to make diagonal slices in quarter-inch, two-track stereo tapes. Saks has seen the changes as the business progressed to two-inch 16-track tape, and then to electronic editing of 48-track digital.

Saks followed Shepard when he left Columbia to join RCA Records in 1974. “I was given Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra as my project. In those days they were big. Very important. They did eight LP’s a year. Classical music wasn’t the small, niche market that it’s become now.” Saks reports that the conductor was in a period of physical decline. (Ormandy had been conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra for 38 years when he started working with Saks. He retired from the position six years later, at age 79.) “His method was to conduct until something went wrong, then stop and start again. I wanted him to do long, complete takes and let the orchestra get excited. Don’t stop when he heard mistakes but go back later and re-do some sections. But Ormandy was adamant. The result was that all his stops caused a loss of momentum and the timing of his records became slower than his live performances.”

Though Saks was only in his 20s, Ormandy sometimes depended on him for help. “One day he had me come to his apartment at the Barclay Hotel [in Philadelphia] to help him connect his Hi-Fi system. I guess he heard that I was in the television business, so I should be an expert at fixing TV sets. I always called him `maestro’ or `Mr. Ormandy,’ and he was a warm, generous man. He gave wonderful gifts for my children’s births – a sterling silver cup and spoon from Tiffany, and a clock that shines numbers onto the ceiling.”

He wasn’t particularly an opera fan at that point in his life, but Saks recorded James Levine conducting the Chicago Symphony, and they hit it off. “Levine was the new music director at the Met. As technology was changing in the late 1970’s, he felt strongly that the Met broadcasts needed to be improved.” So Levine hired Saks, apart from his RCA job, to take over the Met audio. “We put in new lines, a new control room, and it was an interesting challenge. I discovered here’s something I love.”

Gradually Saks did more shows, in addition to symphony and opera. Eventually he was appointed Executive Producer. Two of his most successful projects were his recordings with the Boston Pops and the Canadian Brass.

Saks has won nine Grammy Awards. Four are for producing the Broadway recordings of Into the Woods (1988), Jerome Robbins’ Broadway (1989), Guys and Dolls (1992), and Chicago (1998). His other Grammy Awards are for classical music, including Doctor Atomic in 2012 and Wagner’s Nibelungen Ring in 2013. Saks has a total of 38 Grammy nominations. He also has two Emmy Awards for his audio direction of Metropolitan Opera telecasts and has done close to a hundred televised operas from the Met, San Francisco, Houston, Philadelphia, Verona and elsewhere.

Saks has worked with most of the great Broadway composers. In addition to the productions already mentioned, his other show albums include Candide, Steel Pier, A Class Act, A New Brain, the original Toronto production of Ragtime, Closer than Ever, Once on This Island, Assassins and the revivals of How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying and Once Upon A Mattress.

He spoke about Ed Kleban, the composer of A Class Act. “I never met him. He had a huge hit when he wrote the lyrics to Marvin Hamlisch’s music for A Chorus Line. But he usually wrote his own music and was frustrated that he never had a show of his own produced. In his will, he asked for a theatrical performance of his songs, and that’s how this production got started. An actor playing Kleban attends his own memorial service, then tells us about his life. There are only seven instruments, and I created a sound ambience with minimal reverb so the show sounds intimate.”

Saks developed a close relationship with Kander and Ebb, starting with The World Goes Round, then Steel Pier, Chicago and Cabaret. “Fred Ebb stayed in the background. John Kander does the talking. He’s soft-spoken, the sweetest guy, yet he knows how to get his way. Very organized and specific. He’s an opera expert, you know, as well as a Broadway composer.”

“With Cabaret, there were problems. The pit band was not good because they were hired partly for their appearance, and some of them had to be actors. Only four or five of them play in some scenes. So we brought in lots of extra musicians for the recording. I decided to re-create the theater ambience and have an audience for the songs done in the nightclub, with laughter, applause and the sound of glasses clinking. Director Sam Mendes didn’t like this idea. John and Fred loved it. Neither side budged. Finally we made a company decision to go with it and we informed Mendes. I couldn’t have everyone around during the recording session, but I invited them to a playback session. Mendes didn’t come. We Fed-Ex’d a tape to him, and Mendes hated the audience effects. He said: `Remove them all. It sounds like the Cosby show.’ But we held firm.”

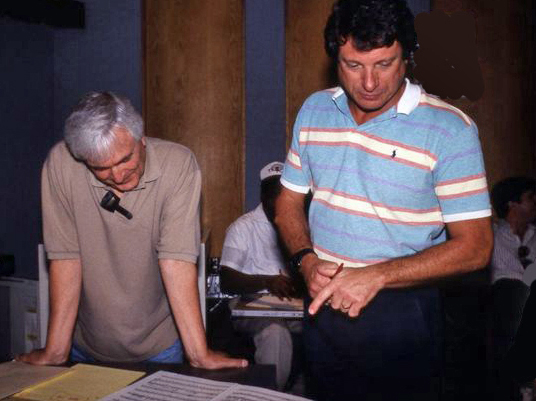

On the right, John Kander with Saks:

About Sondheim: “Warm. Creative. Easy to work with. He’s specific, but he accepts advice from his collaborators.” Saks is particularly proud of his work on Sondheim’s Assassins. “It was done Off Broadway with only three musicians. It had an unusual subject, and when the Gulf War started, people didn’t want to think about assassinations. So business was way down. Sondheim often had been non-commercial but never as unbankable as this. Nevertheless, hit or not, we agreed to record it. We hired 30-plus musicians and got Jonathan Tunick to write new orchestrations. Sondheim was very appreciative. He said it was the best cast album of all of his.”

“In Assassins, the show, there was no finale music. Just a spooky final scene at the Texas School Book Depository. I didn’t know what to do except do the scene as if it were a radio play. John Weidman [author] said `that’s great’ and Sondheim agreed.”

Bill Rosenfield came to RCA first as a writer, then as Director of Artists and Repertoire. “I love Jay. I’m devoted to him,” says Rosenfield. “No one lavishes as much care to detail in the construction of a Broadway album. He winds up knowing a show almost as well as the creators, and he knows how to communicate it aurally. When I was appointed to head A&R, Jay was totally supportive. He said to me, `I don’t make deals; I make records’ and I answered him, `That’s great. I’ll make the deals and you make the records.'”

Aside from his recording and broadcast work, Saks produced the soundtracks of Godfather 3, Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky, Franco Zeffirelli’s La Traviata and Fantasia 2000 with the Chicago Symphony, James Levine conducting.

Saks lives in Ridgefield, Connecticut, with his wife, Linda Nathan, who works with physically handicapped children in an elementary school. Their older son graduated from NYU law school, and their younger from Babson College in Massachusetts.