The world know Louis Kahn as one of the greatest architects of all time, a visionary with extraordinary imagination. I knew him as a friend, and a collaborator. I sat with him and discussed his ideas for the government buildings in Bangladesh and for the Salk Institute in California. But our most interesting conversations were about a more personal creation.

That experience was the direct result of my father’s long friendship with Kahn.

My dad and Lou were the same age, and both worked in center city Philadelphia in professions that previously had been unwelcoming to Jews. My father was an optician who opened his own store at 1624 Spruce Street in 1933, shortly before Kahn opened his architectural studio at 1728 Spruce. Kahn was not religiously observant, and he said that the reason some people discriminated against him was not because of his beliefs but solely because of his ethnic heritage.

Lou had worked at the firm that designed the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1928 and he drew some of the plans for the Rodin Museum that opened in 1930. He had a populist social agenda and modernist aesthetics as he designed projects for Roosevelt’s Public Works Administration and for Jersey Homesteads near Hightstown, New Jersey, where hundreds of Jewish garment workers moved as part of a back-to-the-land movement.

After he reached middle age, Lou became recognized worldwide and was hired by the Jonas Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, by the new nation of Bangladesh, and for other notable projects. Architectural critic Nicolai Ouroussoff of the New York Times wrote, “Kahn’s mythic stature in American architecture is matched only by that of Frank Lloyd Wright; and even Wright is less likely to be spoken of with such reverence.”

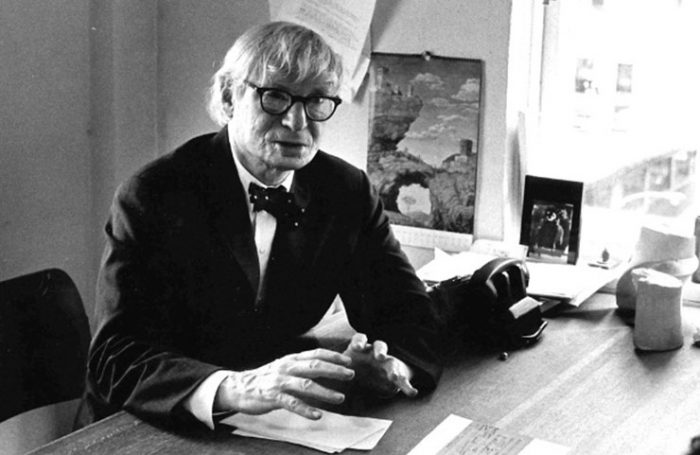

He was an unassuming man, short, muscularly built, with a scarred face which was the result of severe burns when he was three years old.

A showcase for a revitalized Philadelphia was co-designed by Kahn and Edmund Bacon in 1947. A spectacular 30-by-14-foot model of the city center occupied two floors of Gimbel’s department store, attracted thousands of visitors, and won public support for the idea of modernizing the city. Then Bacon became executive director of the Philadelphia City Planning Commission and he rejected all of Kahn’s ideas and ridiculed him as an impractical dreamer.

Among other projects, Kahn recommended large parking towers around the edges of the city center to create a pedestrian-friendly downtown. Kahn described expressways as being like rivers, and “Rivers have harbors, and harbors are the municipal parking towers.”

Among other projects, Kahn recommended large parking towers around the edges of the city center to create a pedestrian-friendly downtown. Kahn described expressways as being like rivers, and “Rivers have harbors, and harbors are the municipal parking towers.”

Bacon became the darling of Philadelphia’s social and political elite, while Kahn rarely was hired to design any public or corporate building in his home town. A notable exception was the Richards Medical Research Building at the University of Pennsylvania in 1960.

During the first half of the 20th century, with its quietly-accepted genteel anti-Semitism, my father, Charles Cohen, hid behind a name which he felt would be more acceptable to a broad public — as Charles Sigismund, optician, which is how he was listed in Philadelphia phone books. (Sigismund was his middle name.) Despite dad’s effort to widen his appeal, the majority of my father’s customers were Jewish professionals who lived or worked in center-city Philadelphia and wanted to patronize “one of their own.” In addition, a large number of non-Jewish artists and musicians came to his store.

In the 1920s and ‘30s the Cohen and Kahn families lived near each other in West Philadelphia. Lou and his wife Esther resided at 5243 Chester Avenue. My father lived with his parents at 4533 Larchwood Avenue, then, as a new husband and father, on 46th Street near Chestnut. While Lou and Esther remained in their house for decades, in 1938 my mom and dad moved to a new home constructed at 6507 Lawnton Avenue, in the Oak Lane section of Philly.

Around the time we moved there, Kahn was hired to design a synagogue for Congregation Ahavath Israel in our new neighborhood. The chairman of the synagogue’s building committee, Barnett Lieberman, was a family friend and his daughter Sylvia babysat me and my younger sister. Because of those connections, we became congregants in that unpretentious structure.

My father had no talent for architecture, but was an amateur painter and a collector of prints. My mother was a pianist, and my parents avidly attended theater and concerts. Lou was an excellent pianist and a painter aside from his architectural drawings. So they (and I) frequently talked together about music and art. I got to know Lou’s wife and their daughter, Sue Ann, who is a flutist, six years younger than I.

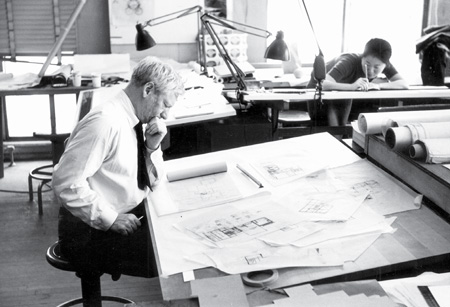

Eventually, my dad purchased a property at 1835 Chestnut Street (Philly’s main shopping street) and the Kahns came there for all their eyeglasses. Lou also brought members of his design staff to Sigismund Opticians. I worked for my father, while also producing and hosting radio programs for WHYY in the evenings.

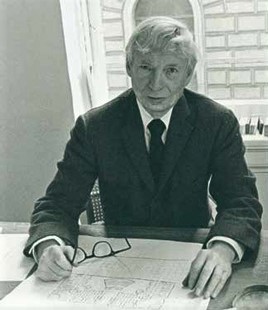

When Lou Kahn developed cataracts, in 1972, he underwent surgery and brought his new eyeglass prescription to us. In those days, such surgery necessitated the wearing of thick magnifying lenses, so his next glasses would have to be much more noticeable than his previous. Lou walked in with his sketch of what he’d like his frame to look like.

Kahn’s works are considered as monumental. This particular creation was only seven inches across. My dad asked Lou to sit down with me and discuss how to execute his desires.

Some of Kahn’s architectural colleagues (such as Philip Johnson) chose to wear small, roundish eyeglasses. Lou told me that function was his main concern and he wanted something larger, to give himself a wider field of vision. He and I discussed the fact that larger dimensions would cause the centers of his lenses to become thicker, and he understood that.

We discussed the principle that we could grind his lenses extremely thin at the edges, but the nature of his prescription necessitated an accelerating center thickness as the longitude increased. In other words, small frames would allow his lenses to be thinner. But Lou Kahn didn’t want to copy his colleagues’s minimalistic look.

What we agreed on was a design with softly curved corners, not nearly as large nor rectangular as the fashionable styles of the 1970s, but not as small and round as Philip Johnson’s or John Lennon’s glasses.

An additional alteration was needed. Lou had drawn a bridge that was centered vertically in relation to the lenses. This looked attractively symmetrical but would cause his eyeglasses to sit up too high, with the top rim bumping against his eyebrows and the bottom being too far above his cheeks. I drew my suggested changes on his drawings and he approved them.

Ed Bacon criticized Kahn’s stubbornness and inability to compromise. That’s the opposite of what I experienced in our collaboration.

I carried our drawing to Joe Danieli, who used the name Joe Daniels and whom we frequently employed to custom-make frames for us. At his walk-up studio on Sansom Street, Joe used cellulose acetate plastic, which the public knows as “tortoise shell”, and fabricated the Kahn frame to our specifications. We then made Lou’s lenses and heated the frames to insert the lenses into the grooves.

After Kahn got his glasses, a four-by-six card of its specifications went into our file drawer, along with the original sketch, neatly folded. This was the same year that Kahn was working on the parliament building for Bangladesh; the opening of his Kimbell art museum in Fort Worth, Texas; and the dedication of his library at the Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire.

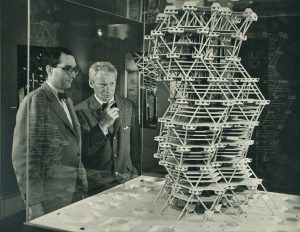

To the right, Kahn and his model for a building opposite Philadelphia’s City Hall, inspired by the double-helix structure of DNA; photo by Sue Ann Kahn:

On March 17, 1974, Khan died of a heart attack in Pennsylvania Station in New York City at the age of 73. Stupidly, I did nothing to preserve or copy our drawing. In 1980 my ailing father sold his building on Chestnut Street and sold his business records to Limeburner Opticians, one of our friendly competitors.

A couple of years later I belatedly thought about its importance and went to Limeburner in search of that drawing. Limeburner’s manager told me: “We sent a mailing to everyone in your files and, if they didn’t come in to get new glasses from us, we dumped their records.”

I find it fascinating that Lou showed interest in the refraction of light reaching his eyes, when a unique part of his architectural creativity was his refraction of, and positioning of, light inside his buildings. As Wendy Lesser wrote in her biography of Kahn, all of his great buildings reveal his interest in light — “how natural light can come in through windows, skylights, holes in the roof.”

Thomas Schielke called Kahn “a master of light” and Kahn talked about the subject: “All material in nature, the mountains and the streams and the air and we, are made of Light which has been spent, and this crumpled mass called ‘material’ casts a shadow, and the shadow belongs to Light. A plan of a building should be read like a harmony of spaces in light. Even a space intended to be dark should have just enough light from some mysterious opening to tell us how dark it really is.”

In our conversations, Kahn was simple and unpretentious. When speaking with other architects, Kahn often used parables, but not with us. He did not indulge in the poetic aphorisms of a guru — such as this famous one that’s been oft quoted:

“If you think of Brick, you say to Brick, ‘What do you want, Brick?’ And Brick says to you, ‘I like an arch.’ And if you say to Brick, ‘Look, arches are expensive, and I can use a concrete lintel over you. What do you think of that, Brick?’ Brick says, ‘I like an arch.’ And it’s important, you see, that you honor the material that you use.”

And he revealed nothing that would make me suspect that this ordinary-looking “old man” — my father’s age — had extramarital love affairs, and additional children born to two single women who worked with him. He clearly compartmentalized his life; thus my remembrances are specific to one small part of his persona.

Wendy Lesser also wrote, “He was a narrative artist. In his buildings, there’s a plot, with surprises.” Certainly in his personal life there were fantastic surprises.

Two of Kahn’s designs: the Eshrick family home in Chestnut Hill and the interior of the Fisher family home in Hatboro.

Below, two views of Kahn’s Parliament building in Bangladesh:

Esherick photo by William Whitaker; Fisher photo by Kyle Weaver; other photos from Kahn Collection/University of Pennsylvania.

To see a related story about Frank Gehry, click here.