L’Amour de Loin (“Love From Afar”) is one of the most respected operas of the young 21st century. Considered as a masterpiece in its construction, it’s been produced throughout Europe, at Santa Fe, and now at the Metropolitan Opera.

But is it a great opera? After seeing it twice, I’m not convinced. You’re not likely to walk out of the theater humming any melody, and the drama is inert.

Although the composer is Finnish, the story is set in France and Libya and is sung in French. A troubadour — Jaufré Rudel, from 12th-century Aquitaine — has tired of fleeting flirtations and he dreams of a true love. A pilgrim tells Rudel about an ideal woman named Clémence in Tripoli, on the coast of Libya. Eventually he travels across the Mediterranean Sea to meet her and both are enthralled with each other. But he has unexpectedly and mysteriously become ill. Their union is too brief and he dies in her arms.

To readers who have asked “what does it sound like?” I’d say it resembles Pelleas et Melisande. Yet L’Amour du Loin has even less action than Debussy’s nebulous tale. (One sarcastic critic opined that “it’s like Pelleas without the laughs.”) Kaija Saariaho invests her music with rich colors and textures. She takes elements of medieval troubadour music and exotic North African motifs and presents them in layers of orchestral fabric.

Woodwinds predominate, often underlaid with the drone of low brass and topped with exotic percussion. Wordless passages for chorus blend seamlessly with the orchestra. The solo vocal writing is not as effective, and often is sing-songy.

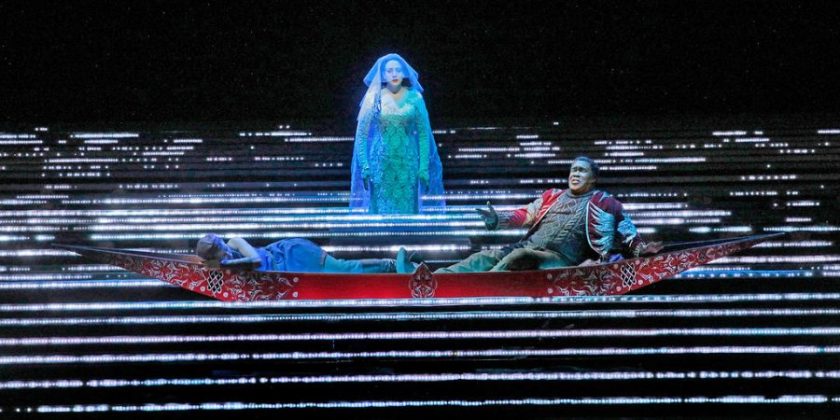

Robert Lepage’s design and direction is creative in a surprisingly modest way. There’s no massive machinery as in his Ring cycle. Instead, 28,000 small LED lights compose glimmering ribbons across the stage and the top of the orchestra pit. Their changing colors and rippling motions effectively evoke the sea. This was a transfixing image when we saw it live at the Met. The HD screening was not able to do justice to it (you need to see it in three dimensions), but Gary Halvorson’s direction had great closeups of the principals.

One of the highlights of the production is the opening of the second act, with the troubadour and the pilgrim crossing the Mediterranean (see photo above). The lights and the orchestra portray the surging of the sea and the ebb and flow of the tides. It’s opening measures approach the tone of Benjamin Britten’s Sea Interludes from his Peter Grimes, yet Saariaho fails to develop a similar powerful climax.

The libretto by the Lebanese-French novelist Amin Maalouf concludes with theological ruminations by Clémence. She denounces God for taking her lover’s life, then comes to accept God as her new “lover from afar.” The religiosity seems imposed. For some attendees, however, this spirituality will be an asset. Admirers rave about L’Amour de Loin being “life-changing.” I, and those around me, just didn’t feel that fever, or drink that Kool-Aid.

The production is worth seeing mainly for the spectacular performance of Susanna Phillips. She’s been a frequent performer at the Met — in frivolous roles like Rosalinda in Fledermaus and Musetta in La Boheme — and never revealed this range of vocal virtuosity. She’s radiant in lyric moments and heart-rending in dramatic climaxes. Her voice soars freely on top notes, then descends to chesty exclamations. In an era where certain women (Netrebko, Fleming) have received massive publicity as superstars, the attractive Phillips deserves similar consideration.

Eric Owens was a vulnerable Jaufré. His voice was less firm, more weary, than usual, probably intentionally as part of his character. Tamara Mumford was strongly reassuring as the Pilgrim.

Donald Palumbo’s Met chorale acted as a classical Greek chorus. The heads of chorus members sometimes bobbed up and down amidst the waves of the sea. The Finnish conductor Susanna Mälkki kept the music surging with emotion.

One small quibble: The vessel that transported Jaufré and the pilgrim across the Mediterranean was roughly the size of a rowboat. It’s hard to believe it could survive the 800-mile distance.

Please share your thoughts with us. Address editor@theculturalcritic.com