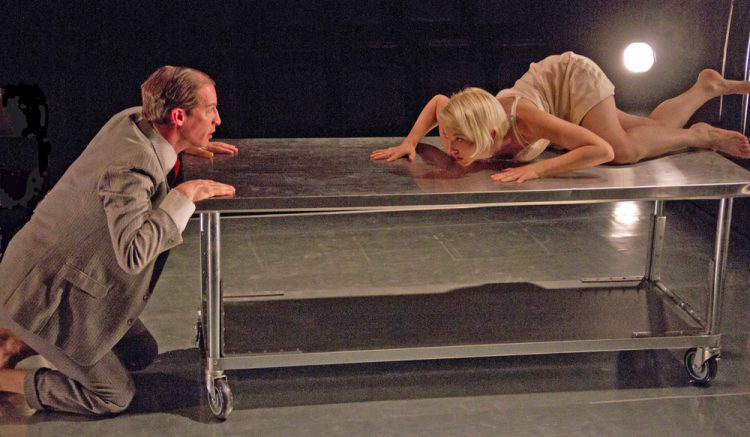

Machinal, by Sophie Treadwell. Brenna Geffers directed for EgoPo Classic Theater, 2016

Once again, the EgoPo theater company has brought life to a neglected play. Machinal opened on Broadway in 1928 and ran for only two months, largely because its subject was deemed to be offensive. Its memory has endured as an icon of Expressionist theater and a rare example of a female writing about the plight of women. (A 2014 Broadway revival ran only seven weeks.)

Most theater-goers today have only a vague idea of what Expressionism is. They are not helped when critics, intending to flatter their readers, use the label without taking time to explain it.

Simply put, the genre emphasizes the expression of emotion. The way in which feelings are portrayed—that is, expressed—is more important than the plot; the telling is elevated above the narrative. Expressionism, as in paintings such as Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” distorts reality for emotional effect. Expressionist plays also emphasize high intensity and stylized movement.

This coordinates with the aim of EgoPo to convey theatrical emotion through body movement. Lane Savadove, the troupe’s founder and artistic director, had this in mind when he selected the name by combining the idea of self, or ego, with the French word for skin, peau, re-spelled.

This production of Machinal is a vivid example of the genre.

The story doesn’t try to surprise us. Sophie Treadwell based her play on a real case where a woman murdered her husband, confessed, and was executed for the crime. A stenographer, Helen, lives with her domineering mother and works in a large office where employees follow established rules. At work and at home, Helen feels oppressed by what society expects of her. Largely to get away from her mother, Helen enters a loveless marriage to her boss.

We see similarities to Elmer Rice’s 1923 play The Adding Machine, which centered on Mr. Zero, an accountant at a large, faceless company. After 25 years at his job, he is replaced by an adding machine. In anger and pain, he kills his boss.

There also are echoes of The Hairy Ape (1922) by Eugene O’Neill, about a primitive laborer who searches for a sense of belonging in a world controlled by the rich. It was presented by EgoPo in 2015. click here

The title implies machinery, and the opening scene is filled with the dehumanizing sounds of telephones, appliances and clerks who repetitively spout clichés of office life. The vice president of the company, George, is a go-getter striving for success. He speaks compulsively in the language of businessmen: ”I put it over; he came across; he signed on the dotted line,” and reveals that even he is fearful of his superiors.

George’s problem is that he, as Robert Zaller perspicaciously wrote, “assumes that a woman too is a machine that should work as designed when her levers are pushed.”

An unhappy Helen sees no means for survival except through marriage, recalling the plight of Jane Austen’s heroines. Her adjustment to marriage is awkward, and an unwanted baby adds to her alienation. She nervously says that she needs to be free.

In a Manhattan speakeasy, George, frustrated by his wife’s unresponsiveness, comes on to a man. Helen, left on her own, meets a handsome young adventurer (Chris Anthony, in the role originated by Clark Gable) and falls in love for the first time. He shows affection for Helen but is committed to a wandering life.

After he leaves her, Helen snaps and murders George.

Mary Tuomanen is perfect in the role of Helen. Pale of face, slight of figure, attractive but almost androgynous, she embodies someone not ready for marriage and motherhood. A Broadway actress in this role hyperventilated and pulled at her hair, while Tuomanen is quiet and passive and thereby is much more sympathetic. Treadwell wrote that Helen “never finds any place, any peace; the woman is essentially soft, tender and the life around her is essentially hard, mechanized.”

Similarly, the George of Ross Beschler is an improvement over his Broadway counterpart. He is awkward rather than repulsive and makes her boss/husband seem oddly sympathetic.

Many scenes moved us emotionally—none more so than the episode in Act II where Helen meets that young man in a speakeasy and falls in love. Suddenly, she’s no longer timid and soft-spoken. There’s a new sense of assurance, and brief happiness. Other powerful scenes are her wedding night, and the frightening childbirth where doctors ignore her needs.

Thom Weaver’s choreography and production design reinforce the emotions. Some facets may seem excessive—such as Helen hiding in a gurney, or the use of gas masks in a hospital—but Expressionism was not known for subtlety.

Editor’s note: EgoPo’s accomplishments are not limited to obscure works. To read just two examples, see reviews of the company’s Death of a Salesman and Diary of Anne Frank on this website.

Below, photo of Mary Tuomanen with Chris Anthony.

Please share your thoughts with us. Address to editor@theculturalcritic.com

Read other reviews on The Cultural Critic