Philadelphia Orchestra, Yannick Nézet-Séguin conducting Schubert/Liszt and Mahler, October 17-20, 2019, Kimmel Center in Philadelphia.

In the summer of 1901 Gustav Mahler composed a single-movement scherzo unlike anything he had previously written. Its music conjures Vienna’s grand Ringstrasse, café houses, country-dance ländler, and waltzes. Mahler said that it described “a human being in the full light of day, in the prime of his life.” Subsequently, he looked for a way to incorporate it into a larger work. The result was his Fifth Symphony, which became a five-movement composition which centered around the scherzo.

Its many riches include an opening trumpet fanfare, a powerful funeral march, and a romantic Adagietto for harp and strings which was his love song to his new bride (made famous in Visconti’s 1971 film Death in Venice.) Also, it has a distinction as Mahler’s first orchestral piece since his First Symphony that is purely instrumental, without a vocal component.

The ambitious work was denounced at the time of its 1904 premiere by the bigoted Viennese critic Ronald Louis:

“If Mahler’s music would speak Yiddish, it would be perhaps unintelligible to me. But it is repulsive because it acts Jewish….with an accent, with an inflection, and above all, with the gestures of an Eastern, all too Eastern Jew. So, even to those whom it does not offend directly, it cannot possibly communicate anything.”

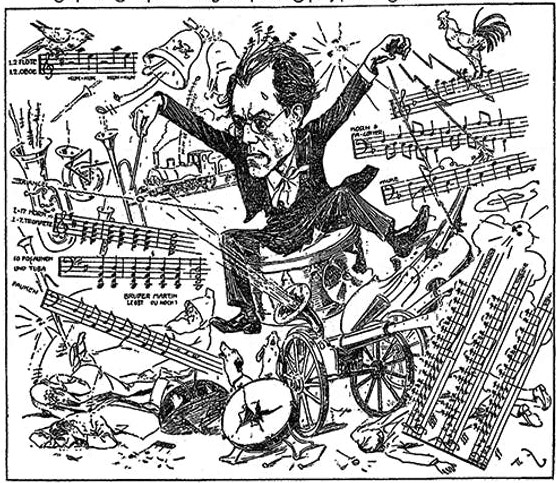

Others attacked it as being too noisy. [See the cartoon at the top of this article.] Mahler’s work was disparaged for many decades. Olin Downes in the New York Times, for example, said “The Fifth Symphony has the same defects that one finds in Mahler’s other orchestral works. Its ideas are commonplace. The orchestration is either swollen or suddenly thin or bizarre. The symphony is prolix and tiresome; the composer never knows when he has said enough. The most pathetic thing about this music is its complete sincerity, its impotent self-torture. His spirit, not his music, commands respect while he seeks vainly to find the creative goal. But he is helpless, and certainly his music will perish.”

All in all, a big challenge for a symphony orchestra.

Yannick Nézet-Séguin took up that challenge with the Philadelphia Orchestra during the middle week of October. This was a magnificent display of extreme emotions, unpredictability, incongruity, violence and repose. From hushed whispering to a blazing finale, YNS led an impressive performance with sharp and purposeful phrasing.

The interpretation was gripping, the orchestral playing gorgeous. Especially important contributions came from French horn Jennifer Montone and the soulful cello section led by Hai-Ye Ni.

Mahler left no explicit program for this symphony, but it clearly portrays a journey from sadness to hope. Many critics describe the funereal first movement as bleak and despairing. I suggest an additional dimension. Mahler had experienced many deaths in his family (eight of Mahler’s thirteen siblings died in early childhood) and here he seems to accept funerals as an inescapable part of life, a reality to be dealt with before moving on. Tragic, yes, but not entirely bleak. This funeral march can be seen as defiant, more than elegiac. Towards the end of the first section, about 25 minutes into the symphony, we can hear the funeral theme rise into a hopeful march.

About that Adagietto — The same year when he started this symphony, Mahler began his romance with Alma Schindler. He was 40, she was 21. Alma previously had an affair with the composer Alexander von Zemlinsky. Mahler married Alma in March 1902. In 1910 she started an affair with the architect Walter Gropius, which shattered Mahler emotionally, a year before his death.

Before intermission, this concert presented Liszt’s orchestral setting of The Wanderer, a solo piano fantasy by Schubert. Frankly, I prefer my Schubert simple and unadorned. It was a pleasure to hear the balding, trim-bearded Louis Lortie as the pianist in dialogue with the orchestra. He created a melancholy mood that was an excellent introdution to the Mahler.