Jacques Offenbach was celebrated as the quintessential French composer, and his Can-Can evokes everything Parisian. The dramatist Albert Wolff wrote that Offenbach “captured the wit and humor of the great city in its moments of explosive mirth, the merry, careless Paris, the Paris that loves to laugh, dance and amuse itself,” and his music also has a “pathetic touch that springs from the heart and goes straight to the soul.”

An Offenbach 200th anniversary organization in Cologne Germany aims to create awareness that he did more than write Can-Can music, presenting an array of operettas, chamber concerts, speeches and panel discussions this year. In Philadelphia the Concert Operetta Theater under the leadership of Daniel Pantano presented excerpts from ten Offenbach operettas to honor his birthday in 2019, as seen here: http://www.concertoperetta.com/pastprod.html.

Yet this exponent of French life actually was an outsider who ultimately was rejected by Frenchmen.

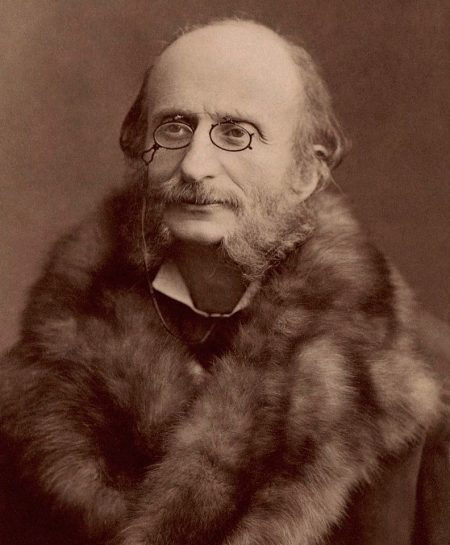

Offenbach’s real name was Jakob Wiener. He was born at Cologne, Germany in 1819, the son of a Jewish cantor. Offenbach moved to Paris in 1833, didn’t know a word of French but soon learned, and he changed his first name to Jacques. He earned his living playing cello in the orchestra of the Opera Comique. In 1850 he became conductor of the Theatre Francais and in 1855 founded his own theatrical company, the Bouffes-Parisiens. His first successes were the equivalent of Off-Broadway, in a tiny theater with restrictions on the number of performers who could appear on stage, forcing him to write for small casts.

His emergence coincided with the inauguration of Napoleon III as emperor of France. The reign of this nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte (from 1852 to 1870) was marked by the rise in nouveau riche merchants and financiers, who implemented a grand reconstruction of Paris. The emperor gave them social status which had previously been exclusive to those who were noble-born. Royalty and the new rich non-royals shared a fondness for lavish living and for the arts. Also under Napoleon III, the first women students were admitted at the Sorbonne, and women’s education greatly expanded.

In the opinion of Louis Napoleon’s followers, grand opera was too long, and required too much of their time. They preferred light musical entertainment, and Jacques Offenbach’s creations filled the need. He wrote parodies of classics, and he portrayed gods and goddesses as lusty modern men and women. His tunes were cheerful, with witty lyrics — and he became the most popular composer in the new French society.

Rossini, living in retirement in Paris, called Offenbach “the Mozart of the Champs-Élysées.”

Offenbach wrote larger works like Orphee aux Hades (Orpheus in the Underworld) in 1858. Then came La Belle Helene, a satire on Helen of Troy, in 1864, and La Vie Parisienne in 1866. The Grand Duchess of Gerolstein in 1867 was a satire on the Russian court of Catherine the Great and a critique of militarism.

The German-born Offenbach was the darling of Paris, his operettas characterized by wit and bawdy sexuality. Offenbach became, in the words of one critic, “more Parisian than the headwaiter at Maxim’s.”

His march “Vive le France” became a popular patriotic anthem. As Irving Berlin did in America in the next century, this immigrant Jew became the nation’s leading writer of patriotic songs. But Hector Berlioz was critical; he compared Offenbach’s theater with houses of ill-repute where Offenbach peddled “barbarism and flesh for sale.”

Louis Napoleon doubled the area of the French overseas empire. When unrest developed among France’s poorer classes, he escalated his hostility to Prussia. The writer Prevost-Paradol said that “Distracting men’s minds and diverting them with the hope of territorial aggrandizement” was a natural choice for “absolute governments to choose to get out of difficult situations.” Accordingly, Louis Napoleon went to war against Prussia which was ruled by Kaiser Wilhelm and Prime Minister Bismark.

In this warlike atmosphere, Offenbach chose a diversionary entertainment for his next creation. La Perichole in 1868 was a romantic comedy which mocked the debauchery of the Spanish empire in the previous century. Conductor Emmanuel Villaume says that “Offenbach was criticizing the very society he entertained, for its vanities, its frivolities and for the way that its leaders abused their power.”

In September 1870 there were four theaters in Paris featuring operettas by Offenbach. But during that same month, the Prussians defeated the French in the battle at Sedan and took Louis Napoleon prisoner. Two days later a Republic was declared by the mobs in Paris. In March of 1871 German troops marched down the Champs-Elysees, the Emperor and Empress went into exile and the Second Empire came to an end. Its territory was reduced in size as the victorious Germans seized the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine.

The change of regimes ruined Offenbach’s career. Frenchmen regarded Offenbach as a representative of the Imperial Napoleonic regime. In addition to that, the new French Republican government opposed the frivolous entertainment that was associated with the Empire. Offenbach’s work was denounced as being decadent, and his musicals no longer were performed. French hatred of the Germans spilled over into distrust of the composer who was born and raised in Germany. A leading newspaper called him “a Prussian at heart.”

So Offenbach felt rejected and abandoned. But Louis Napoleon, in exile in England, continued until the day of his death to ask for Offenbach’s music to be played for him.

Shunned at “home,” in 1876 Offenbach visited America to participate in its Centennial Celebration in Philadelphia and conducted concerts at a new building, Offenbach Garden, at Broad and Cherry Streets. (The building was demolished in 1892 to permit construction of the Odd Fellows Temple, which still stands across Broad Street from the Academy of the Fine Arts.) And Offenbach wrote a book for an American publisher about his American experience.

His description of Philadelphia is interesting: “The streets are very fine, and wide enough to rival the Boulevard Haussman. On both sides are houses of red brick with window-frames of white marble. A new City Hall is being built in white marble. My friends and I didn’t know how on earth to spend our Sunday, for the [Centennial] Exhibition is closed. We were advised to go to Indian Rock in Fairmount Park. It takes two hours to get there, but the park is endless. It is impossible to imagine anything finer or more picturesque; small streams winding under the trees, green valleys, shady ravines, splendid woods.”

He added, “Negroes cannot enter cars or other public conveyances. On no account do the theaters admit them. And if they are received in the restaurants it is only to wait on the white guests.” This was more than a decade after the end of the Civil War!

Offenbach wrote caustically, “At the Continental Hotel all the waiters are negroes or mulattos. As a waiter in another hotel it is necessary to have a coating of liquid blacking on your face. I have an idea that Alexandre Dumas must have passed some time here, for the portrait of our great novelist is reproduced here to perfection.” (Dumas’s mother was Afro-Caribbean.)

It’s interesting that this visitor was so concerned about racial discrimination in America.

Physically ill with gout, and depressed, Offenbach began work on the most serious opera of his career, The Tales of Hoffman, which described the life of a depressed and alcoholic writer. While his other works were labeled “opera bouffe” or “opera comique,” Tales was called an “opera fantastique.” It was the last thing that Offenbach wrote. He died October 5, 1880, of gout at the age of 61.

In the finale of Tales of Hoffman (a scene restored in the Met’s 2009 production by Bartlett Sher), the muse comforts a bedraggled, despondent writer, “Smile upon your sorrows with serenity. One grows through tears.”Below, anniversary parade in Offenbach’s hometown of Cologne: