Philadelphia Orchestra Festival of Paris. January 2017.

One of the best innovations by Yannick Nezet-Seguin in Philadelphia has been his annual festivals devoted to the music of one specific city. In January 2015 he spotlighted St. Petersburg. In 2016 it was Vienna. In 2017 he has turned to Paris.

In each of these tributes, YNS has delved into the overall culture, not merely the compositions. In the latest three-week exploration, he faced the challenge of how to encompass the vastness of Parisian heritage in the limited time of three concerts lasting two hours each. I’m disappointed that Yannick devoted a considerable amount of that time to composers from regions far from Paris, such as Chopin and Stravinsky. Why schedule music that Ravel wrote about Spain, and that Berlioz wrote about Italy? Considering the wealth of material written in Paris and about Paris by Parisians, that’s a waste of resources.

Where was music by Rameau, Lully, Gounod, Massenet, Charpentier, d’Indy, Debussy? Especially since they wrote many pieces about the culture of Paris. It would have been a pleasure to hear something from Christoph Willibald Gluck, who was the music teacher of Marie Antoinette and wrote numerous French operas.

I regret the lack of Parisian ballet during the Renaissance, and also the cabaret and music hall music of the 19th century, and both jazz and serial music in the 20th. Pierre Boulez, Olivier Messiaen and Edgard Varèse could have been on these programs. I also would have welcomed Satie, Auric, Durey, Milhaud, Honegger, Poulenc and Tailleferre.

I normally admire Nezet-Seguin’s programming, and his conducting, and his complete Daphnis et Chloé in November was a clever way to lead into this festival. But on this occasion he needlessly scattered his shots.

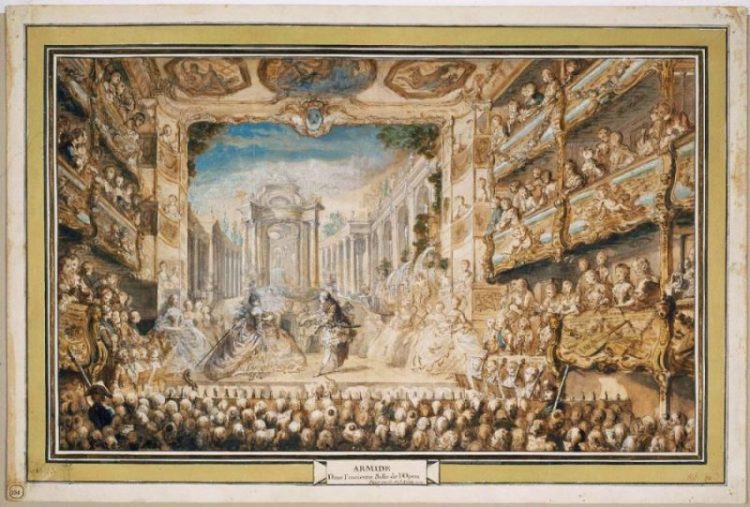

The lobby of the Palace Garnier opera house:

Nézet-Séguin did make some fascinating picks, such as a seldom-heard gem by that man from Lorraine, Florent Schmitt (1870-1958): an orchestral suite from his ballet La Tragédie de Salomé. Its syncopations and percussive chords anticipate Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring which was written five years later.

Schmitt was part of the group of poets, painters and musicians who met regularly for breakfasts, known as Les Apaches (or renegades or hooligans, according to its members). His ballet about Salome became a vehicle for the dancer and dramatic actress Ida Rubinstein, a Russian-Jewish femme fatale who commanded the limelight in Paris. Her sensuous disrobing excited audiences as Cleopatra, and Jean Cocteau described Rubinstein “like the pungent perfume of some exotic essence — ethereal, otherworldly, divinely unattainable.”

Rubinstein commissioned composers for her productions, and in 1920 she chose Schmitt over Stravinsky for Antony et Cléopâtre because he was considered the foremost “orientalist” composer in the world. Salomé, Oriane et le Prince d’Amour and Salammbô were Schmitt’s and Rubinstein’s other “oriental” collaborations.

Schmitt seemed to have an appealing persona until we confronted the fact that, as a music critic for Le Temps in November 1933, he rose from his seat at a concert, denounced Kurt Weill’s music, and led shouts of “Vive Hitler!” He worked for the pro-Nazi Vichy regime in the 1940s, as did Joseph Canteloube.

These concerts thus, indirectly, remind us of the terrible fact that many Frenchmen, driven by nationalism, anti-Communism, anti-Semitism, or opportunism, collaborated with Hitler. Prime Minister Pierre Laval said that “parliamentary democracy has lost the war; it must disappear, ceding its place to an authoritarian, hierarchical, national and social regime.” The government in Vichy agreed to turn over any German citizens within the country upon German demand, including persons who had entered France seeking refuge from persecution. The French government opened concentration camps where it interned Jews, gypsies and homosexuals, and executed many of them during the war years. Marcel Ophüls’s film The Sorrow and the Pity documented this, while Charles de Gaulle represented a so-called Free France movement in exile that opposed the Vichy government.

Canteloube (1879-1957) was a musicologist who collected traditional folk material. He celebrated the beauty of his home region by orchestrating its peasant songs. Songs of the Auvergne is his most lasting composition. It was a wonderful demonstration of the rich and nuanced mezzo voice of Susan Graham.

The other three pieces on the opening week’s program were brief trifles that commemorated the undeniable talents of Chabrier, Fauré, Saint-Saëns and Ravel. The third week’s program included three more pieces by Ravel — Alborada del gracioso, Rapsodie espagnole, and Bolero, which would be more appropriate in a tribute to Spain, not on an overcrowded homage to Paris.

Nézet-Séguin, as I noted earlier in this article, spotlighted people who moved from elsewhere to Paris. For example, Serge Diaghilev came from Moscow in 1907 and presented concerts of Russian music. In Paris in 1909 he launched his famous Ballets Russes which presented the premiere of Petrushka.

Nézet-Séguin led Stravinsky’s score for Petrushka with a floating quality that seems appropriate for a ballet. In conversation afterwards, Yannick said that the floating, airy sound reminds him of French music, which is an interesting argument for including it in these concerts. Petrushka features irregular rhythms with unusual colors and timbres. We heard jazzy brass, quivering clarinet, scampering flute, belching bassoon and insistent tympani, while the string players changed quickly, back and forth, from plucking to bowing. One wonders why it’s not nearly as frequently performed as Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps, premiered two years later. The two pieces have similar nervous energy and propulsive force.

The story and the composition are Russian, and some of its melodies are actual Russian folk songs. The impresario Serge Diaghilev came to Paris with his countrymen Stravinsky, the designer Alexander Benois, and the choreographer Mikhail Fokine for Petrushka’s premiere in 1911, and that premiere was the only link to Paris.

I’m thankful that Yannick Nézet-Séguin led the lovely, impressionistic D’un matin de printemps (“From a Spring Morning”) by Lili Boulanger. She was the younger sister of Nadia Boulanger, the famed teacher of such diverse pupils as Aaron Copland, George Gershwin, Quincy Jones, Virgil Thomson, Daniel Barenboim, Philip Glass and Astor Piazzolla. Lili suffered since childhood with an immune deficiency and Chrone’s Disease, and she died in 1918 at the age of 24. Her piece was pleasing while, simultaneously, underlining the point of the festival. The composer and her sister were a vital part of Paris’s musical life.

The Philadelphia Orchestra’s next Winter Festival, in 2018, will explore music from, and inspired by, the British Isles.