Azul. La Fábrica Theater, Philadelphia, August 2017.

Did you ever wonder why Picasso, for awhile, chose to paint in blue? The earliest stage of his famous career is known as his Blue Period, and this new play by Tanaquil Márquez shows how and why he made that choice.

La Fábrica is Philadelphia’s first bilingual theater company, created to present bold Spanish-English productions. Márquez is co-founder of the company and directs La Fábrica’s Azul as well as being its author.

Azul, the Spanish word for blue, shows the young Picasso at a crucial point in his life, 1900 to 1904, in Barcelona and Paris. It interweaves flamenco music and dance to create a dramatic canvas of Picasso’s emotions that led him to paint primarily in somber shades of blue.

It is imaginatively staged in the Drake Theater. Liliana Ruiz is a spectacular soloist and her flamenco dancing would be worth the price of admission all by itself. She leads a group of six dancers who introduce the action and appear frequently throughout. At key moments, the principal actors join in the dancing — even Picasso, in a memorable coup de théâtre (or perhaps I should use the Spanish word bomba).

Time after time, Márquez provides striking visual images. Some of these are violent, while others are more subtle. For instance, one of Picasso’s best-known works from this period is The Old Guitarist, which is visually evoked by music director Blane Bostock who sits cross-legged as he plays a guitar solo to introduce Act II.

Picasso was turning 19 when he relocated from Barcelona to Paris, struggling for recognition. He is electrifyingly portrayed by Zach Agular who has some facial resemblance to his character at that age.

Rooming in the Montmartre district with his friend from Spain and fellow painter Carles Casagemas (Cameron DelGrosso), the two men compete for the attentions of women, especially Odette (Paloma Irizani) and Germaine (Sol Madiaga), with the aggressive, seemingly confident Picasso always prevailing. Carles’s plight is exacerbated by an erectile dysfunction which makes him an object of derision among the women in Montmartre. When Casagemas shoots himself to death in a café (which he actually did on February 17, 1901) Picasso feels guilty and enters a period of depression.

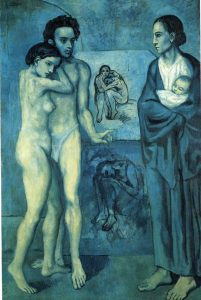

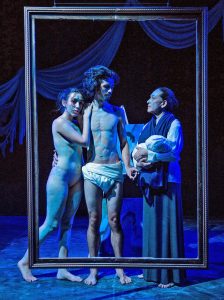

Act II deals with Picasso’s attempt to fight “like a picador” to overcome his blues. He expresses how he feels by changing his color palette, saying “same painter, different perspective” and by choosing new models such as prostitutes, ill women and prisoners. This builds to the creation of his famed doleful painting which ironically is titled La Vie. It includes a mature woman holding an infant, a woman who looks like Germaine, and a man who resembles Casagemas. The picture comes to life before us in a scene reminiscent of Sondheim’s Sunday in the Park With George.

The actual La Vie measures 6 feet tall and 4 feet wide and is owned by the Cleveland Museum of Art. Playwright Márquez frequently saw it when she was a student at nearby Case Western Reserve University, and she took inspiration from it.

In Act II, the charismatic DelGrosso takes on the role of a second historical person, Max Jacob, the French poet, painter and critic who befriended Picasso and who later died in a Nazi concentration camp. DelGrosso does so with a dextrous change of body language and vocal tone. Everyone in this act, by the way, wears or carries something blue (scarves, ties, fans) and has blue facial makeup. David Reece Hutchison provides the costumes, while Veronica Ponce de Leon does the makeup.

This ambitious production is performed by talented individuals who act convincingly and passionately, and speak fluently in English, Spanish, and French. Whenever any of the Hispanic characters talk to each other they do so in Spanish, which is logical but which poses a problem for those of us whose Spanish is rusty. When this company receives additional funding — which it deserves — I hope it will supply projected translations. In the meantime, the animated movements and facial expressions of the actors make it relatively easy to understand them even when you don’t get every word.

Just as Picasso emerges in this play, so does Márquez as a significant playwright and director. Even though I have had considerable exposure to Picasso, this production makes me better understand and appreciate him as a person, which I mean as a heartfelt compliment.

This review originally appeared in DC Metro Theater Arts.

The original La Vie, courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art, and on stage: