When I heard in 2004 that the Bertelsmann music group from Germany was merging with the Sony Corporation from Japan, I assumed it was just another power play among big businesses that had no relevance to those of us with artistic interests.

But wait a minute! Bertelsmann Music Group is better known as BMG, which is the successor to RCA Victor, the company that popularized phonograph records, and also successor to the Radio Corporation of America, which started the first radio network, NBC. And Sony Music is the heir of Columbia Records, which once was dominant in combination with CBS radio and TV and Columbia Artists Management.

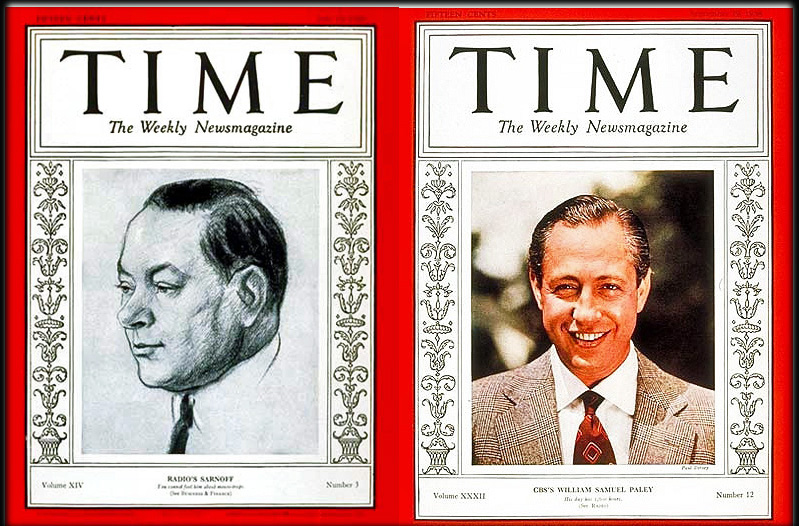

The merger was as if the Republican party merged with the Democrats. Now these two, polarized leaders of the music and entertainment business became one company. It’s interesting to note that it’s run by men with no background at all in music — although, truth be told, the founders weren’t musicians either. David Sarnoff actually was a telegraph clerk, and William Paley was a cigar salesman. The merging of their empires reminds me of some personal contacts, and I’d like to share my memories of those men and their achievements.

Thomas Z. Shepard, who produced show and classical albums for both companies, says that the record business has always been a people business. Shepard’s career started in 1960, but what he says was true right from the start of the two companies.

My father was friendly with Paley’s family, while later, on my own, I got to know the Sarnoffs. How easy would it be to talk with the CEO of today’s billion-dollar companies? Well, one afternoon my phone rang, and a woman’s voice said, “General Sarnoff would like to talk with you.” Sarnoff was one of the most feared men in the world, and here he was phoning me concerning a story I was working on.

My father was friendly with Paley’s family, while later, on my own, I got to know the Sarnoffs. How easy would it be to talk with the CEO of today’s billion-dollar companies? Well, one afternoon my phone rang, and a woman’s voice said, “General Sarnoff would like to talk with you.” Sarnoff was one of the most feared men in the world, and here he was phoning me concerning a story I was working on.

David then was 78 years old and was called “General” because of the honorary rank which President Roosevelt gave him for his service to the nation in World War II.

Born in 1891 in a shtetl near Minsk, Russia, he came to the USA as a child. He learned how to operate telegraphs and got a job doing so atop the Wanamaker store in New York, from where he picked up the Titanic distress signals in April of 1912. Sarnoff was only 21 when he alerted the world to the sinking of the Titanic . The following year, he became assistant chief engineer for the Marconi telegraph company and quickly worked his way up in management.

At the end of World War I he joined other Marconi executives in starting the Radio Corporation of America. To most people, radio was a gadget, but to Sarnoff it was a potential source of entertainment. While others at RCA concentrated on trans-Atlantic communications, David predicted that radio would be “a household utility” and he focused on broadcasting and on the manufacture of home radio receivers, which he called “music boxes.”

He popularized the idea of broadcasting, a word we now take for granted. The hobbyists who used radio to communicate with each other said they were using narrow casting; Sarnoff playing music for the masses was using broad casting. Under his leadership, RCA became America’s fastest-growing company. Between 1921 and 1924 the sale of radios increased 15-fold from 100,000 to 1,500,000 a year. David became a millionaire.

In 1926 Sarnoff formed the first radio network, the National Broadcasting Company. One year later, Sarnoff became the partner of Joseph Kennedy (yes, that Kennedy, the father of JFK) as a motion-picture producer and distributor. RCA Photophone, the company run by Kennedy and Sarnoff, needed theaters in which to exhibit its movies, so it acquired the vaudeville houses of Albee (playwright Edward Albee’s parents), Keith and Orpheum under the new name of Radio-Keith-Orpheum, or RKO. All of its films started with a shot of a radio transmitting tower and the slogan “A Radio Picture.”

Next came the purchase of the world’s largest record company, Victor Talking Machines of Camden, New Jersey. Its logo was Nipper, a dog, listening to a Victrola, with the slogan “His Master’s Voice.” The initials of this slogan led to another corporation, named HMV. Its European division was called Electric & Music Industries, or EMI, which was not included in the 2004 merger.

Sarnoff’s performers appeared on radio, in movies and on records, cross-promoting all three products. RCA even bought out two song publishers, Leo Feist and Carl Fischer, so he could make money from sheet-music sales of songs his stars were singing.

In 1930 RCA and RKO joined in the formation of Rockefeller Center, which Sarnoff re-named Radio City. Two RKO theaters were included in the plans, but the Depression caused the company to settle for only one, the Radio City Music Hall. The tall skyscraper in the middle of Radio City was — and is — the RCA Building, housing the offices of RCA and NBC. It was there, in the 53d-floor executive office suite, that I visited with Bob Sarnoff (David’s son and the president of NBC) and Manie Sacks the year that I graduated college. On the right, David Sarnoff at his desk:

Manie (pronounced “Manny”) was a Philadelphian who became artists & repertoire man for Columbia Records, developing close relationships with Frank Sinatra and many other singers. Finding himself being forced out of Columbia in a corporate power play, Manie negotiated an even better deal with Sarnoff, and he was hired as vice president of the whole shebang at NBC and RCA Victor. Sacks died of leukemia at age 56 in 1958.

NBC dominated broadcasting so completely that it owned two stations in many cities and ran two networks, the Red and the Blue. The government decreed that the Blue network become independent, and afterwards it changed its name to the American Broadcasting Company, or ABC. RCA also bought ownership of Random House publishers, Whirlpool appliances and Hertz car rental.

Meanwhile, back in the mid-1920s, entrepreneur Arthur Judson dreamed up what was to become RCA/NBC’s biggest rival. Judson then was the manager of the Philadelphia Orchestra, which was a hot attraction with its handsome young conductor Leopold Stokowski. Judson signed up concert soloists, singers and conductors who gave him the right to manage their careers. When he hired his clients to appear with the Philadelphia Orchestra, he was cleverly working both sides of the street at the same time. Then he went one step further by also becoming manager of the New York Philharmonic and several other orchestras — in effect working both sides of many streets simultaneously. Everyone in the classical music biz was in awe of Judson’s power.

Judson saw the potential of radio and recordings. Accordingly, he organized a radio network in 1927 which he called United Broadcasting until he got the Columbia Phonograph Record company as an investor. That record company had been created to sell Edison dictation equipment in the District of Columbia (thus the name) and then they branched out into 78 rpm records. Judson persuaded Columbia executives to bankroll the network to help promote the sale of their records, and he agreed to change the name of his network to Columbia. Columbia Phonograph lost money during the first year of the enterprise and pulled out, but the Columbia Broadcasting name continued.

Judson then brought in as partners three Philadelphia men whom he knew from their support of the Philadelphia Orchestra—the brothers Ike and Leon Levy and Jerome Louchheim. The Louchheim family eventually became the distributors of Columbia Records. The Levy brothers owned radio station WCAU which was CBS’s Philadelphia affiliate. They convinced their friend, Sam Paley, who owned a cigar company in Philadelphia, to buy an interest in the network. Leon Levy at that time was courting Sam Paley’s daughter, Blanche. Leon married Blanche Paley in 1928 and in that same year Blanche’s 26-year-old brother, Bill Paley, became principal stockholder of the radio network when his father gave him the stock as a birthday present.

The small group divided the responsibilities inside their youthful kingdom. Full of programming ideas, Bill Paley threw himself into running CBS, while the Levy brothers ran WCAU and a retail radio store in Philadelphia, and Judson concentrated on running Columbia Artists Management and all those symphony orchestras. WCAU’s house orchestra was led by Philadelphian David Raksin, who became famous as the composer of “Laura.” (see separate story about him: click here)

My father introduced me to the Levys, who were his lodge brothers in B’nai Brith. Leon was a dentist and Ike was a lawyer, in addition to being major stock holders in CBS and the owners of WCAU. We watched the New Years’ Mummers Parade from the warmth of Ike’s office overlooking the parade route, and on another occasion he gave this kid some career advice. I met with WCAU’s News Director, Charles Shaw, who was one of “Murrow’s Boys” from World War II. Shaw offered me a news job after I completed college and my military obligation, but I wound up going into music and the arts instead.

Back in the 1930s, Sarnoff noticed the successful tie-in between CBS and classical orchestras, so he decided to become a symphony impresario also. He hired Arturo Toscanini in 1937 and built an orchestra especially for him, the NBC Symphony.

Ted Wallerstein, the head of RCA Victor Records in the 1930s, was a Philadelphia neighbor of Ike Levy’s. Levy complained one day to Wallerstein about Victor’s choice of repertoire. Wallerstein responded that Ike should get his own record company and see if he could do a better job. So Levy and Paley bought Columbia Phonograph, which had briefly been an investor in CBS at the start. Then Paley stole Wallerstein from RCA Victor to run Columbia Records.

Until then, Victor dominated classical sales and popular with Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw, Tommy Dorsey, Arturo Toscanini and Leopold Stokowski, all under contract to RCA. The Victor label also recorded show music, including Cole Porter singing his own compositions. The company issued the hit songs from many Broadway musicals, though not usually with the original cast members. Under Wallerstein, and later, Goddard Lieberson , Columbia surpassed Victor’s connection with show music. Columbia made further inroads by signing Benny Goodman and, temporarily, Stokowski, who was known to a vast public for his film, Fantasia. Here’s how that happened:

When Stoky quit the Philadelphia Orchestra and formed the All-American Youth Orchestra in 1940, he planned to take his new band on a tour to Latin America. RCA Victor promised to sponsor the orchestra’s tour and record it. But Sarnoff changed his mind and decided to send Toscanini to South America instead. Stokowski’s manager, Michael Myerberg, was furious and complained that Toscanini was Italian and most of the NBC Orchestra was Italian, while the youth orchestra, made up of American kids, would be a much better advertisement for the USA.

Hitler and Mussolini were conquering Europe and were forging cultural ties in South America. President Roosevelt invited Paley to the White House and, over sandwiches, told him that he wanted to counter Hitler by sending cultural attractions from the USA to its Latin neighbors. Paley suggested sending Stokowski and the All-American Youth Orchestra, saying that he would record them on Columbia if the U.S. government made the traveling arrangements. Roosevelt agreed and instructed Secretary of State Cordell Hull to do so. When Sarnoff heard about that deal, he was so angry he was determined to get Stoky back in his fold. According to Myerberg, Sarnoff also determined to crush the youth orchestra.

The Stokowski South American tour was a success, and he led his kids on a North American tour in 1941. But then the army began drafting some of its young musicians, and wartime gas shortages thwarted the orchestra’s touring plans and led to its demise. Sarnoff was now a brigadier general in the army, and Myerberg told me that Sarnoff may have vindictively arranged for the drafting of some of Stokowski’s players. Although the All-America Youth Orchestra was now annihilated, Sarnoff told Stokowski that he would personally take care of him.

Sarnoff made a place for Stoky back at RCA by doing some elaborate reshuffling. He got Toscanini named as Principal Guest Conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra, thus leaving the leadership of the NBC Symphony somewhat open, and then he hired Stokowski as co-conductor of that radio orchestra. Toscanini’s image was one of single-mindedness and purity while Stoky’s was as a showman and creator of lush sounds. Their contrasting approaches did not mesh. The clash of two egos doomed the arrangement. The two conductors disliked each other, although they never criticized each other publicly. For their NBC broadcasts, each jockeyed to get the premiere performances of newsworthy compositions. Toscanini won most of the battles because he was older, and he was at NBC first.

So Sarnoff yanked Stokowski from the NBC Symphony and formed a special entity to keep Stoky happy— Leopold Stokowski and “His Symphony Orchestra,” which was made up of freelance musicians and existed only for recording sessions and therefore cost NBC very little money. Stokowski was aware how important the financial bottom line was to Sarnoff, so he hired a small number of musicians and made the orchestra sound fuller by using multiple microphones, placed at varying distances from the instruments. Cellist Leonard Rose complained to me that this was “phony” music but many other observers called this evidence of Stokowski being a “recording genius.”

In 1954, Sarnoff decided to eliminate the expensive NBC Symphony Orchestra, and he forced Toscanini into retirement. Toscanini broke down during his final concert, dropping his hands to his side. NBC execs said that this showed he was senile and his retirement was overdue, but Toscanini’s son said it was because the conductor was furious that Sarnoff was breaking up the orchestra.

From the 1930s on, CBS and Columbia Records ran neck-to-neck with NBC and RCA Victor in popularity. They seemed to take turns in winning competitions. CBS won prestige for its news coverage, led by Edward R. Murrow, during World War II. On the other hand, CBS’s color television system never caught on, and RCA’s achieved universal acceptance. Paley stole some of NBC’s biggest radio stars in the 1940s and forged ahead in radio and TV ratings. CBS won a battle of technology when its LP records became the industry standard, beating out RCA’s 45-rpm system.

Of special interest to the theater community was the development of original cast Broadway recordings by Columbia. Although Decca recorded almost all the songs of Oklahoma! with the original cast in 1943, Columbia made an album starring Nelson Eddy which included even more of the music. Under Goddard Lieberson’s direction, Columbia became the foremost promoter of Broadway show albums. My Fair Lady was offered to RCA / NBC’s Robert Sarnoff, a boyhood friend of Alan Jay Lerner. Sarnoff didn’t respond, while Lieberson did. As the sole backer of the musical, Columbia made a fortune on its investment.

Manie Sacks produced the Kiss Me, Kate album for Columbia in 1949. Columbia also captured the original productions of Finian’s Rainbow, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and South Pacific. RCA Victor did Brigadoon and Paint Your Wagon during the same period. Columbia grabbed more and more of the hit shows in the 1950s and 60s, but RCA Victor tried to stay in competition by recording alternate versions of the same shows with non-Broadway casts. Occasionally RCA won the bidding for major hits like Fiddler on the Roof and Hello Dolly in the 1960s.

For a period in the mid-1970s, RCA did better. Ken Glancey left Columbia to become head of the record division at RCA and he hired two young producers of show albums who also had worked at Columbia, Thomas Z. Shepard and Jay David Saks. This wooing of talent marked the intense rivalry between the two record companies in the area of show music. Shepard says that the attitudes of the two companies were completely different:

“The aesthetic at Columbia was autonomy. RCA Victor was paternalistic. Lieberson at Columbia developed the recording of shows into an art form, revising and tailoring the score for the home listener. Lieberson, a musician himself, said that you could turn a musician into a businessman but not vice versa. Columbia was eager, young and brash, while RCA was the landed gentry of the record industry.” During this period, Sondheim came on board RCA because he felt that Glancey really understood and believed in his work and would go to bat for him.

On the left, Sondheim with Tom Shepard at 1981 recording session.

On the left, Sondheim with Tom Shepard at 1981 recording session.

Glancey replaced George Marek, who was a cultured man but pedantic and professorial. Glancey, on the other hand, had the education and taste of Goddard Lieberson, and, according to Tom Shepard, “the charm of a Noel Coward.” The personalities of specific people made a world of difference.

Arthur Judson died in 1975 at the age of 93. David Sarnoff retired in 1969, turning his empire over to his son Bob. David died in 1971 at the age of 80. Robert Sarnoff died in 1997 at age 78 and General Electric purchased the NBC radio and TV networks while the record company became part of Bertelsmann Music. Bill Paley was still serving as chairman of CBS when he died in 1990 at age 88. Now all the players are long gone and their companies are history.

Please share your thoughts with us. Address to editor@theculturalcritic.com

Read other reviews on The Cultural Critic