The Rigoletto production at Santa Fe in August of 2015 was odd in appearance but very strong in sound, and that’s what’s important.

The Hawaii-born Quinn Kelsey was a superb Rigoletto. His large and penetrating voice transfigured into poignantly refined singing during the intimate scenes. Georgia Jarman was a slender and youthful-looking Gilda, perfect for the part, with an appropriately sweet voice.

Nicole Piccolomini made a strong Maddalena, sensuous in looks with a resonant and well-focused chest voice. Bass Peixin Chen was spine-chilling as the assassin Sparafucile. Bruce Sledge sang the Duke of Mantua cleanly but without the ringing voice or glamorous persona one would wish.

The duets between Rigoletto and Gilda tore your heart out, as Kelsey and Jarman used melting tones to express the affection of father and daughter. The supreme tragedy of Rigoletto is that the jester, despite his flaws, loves his daughter and wants to protect her from all harm. Of course that doesn’t happen. His love for her and desire for vengeance against the duke becomes the source of his daughter’s death and the opera ends with horrible catastrophe.

Both singers were rhythmically secure as well, and belted a rousing finish to their duet at the end of Act II: “Si Vendetta, tremenda vendetta!” (“Yes! Revenge, terrible revenge!”)

Director Lee Blakeley and designer Adrian Linford set the drama in Verdi’s time instead of the 16th century specified originally. Victor Hugo wrote Le Roi s’amuse (“The King’s Amusement”) depicting King Francis I of France as an immoral womanizer. Hugo’s translator called it “an attack on the rights and privileges of monarchy.” Verdi’s operatic version premiered in 1851 with the king turned into a duke to placate censors.

Yet Verdi kept the period to be the Renaissance. The stage direction for Act I is “a magnificent hall crowded with knights and ladies in rich attire.” The only noticeable effect of this production’s time-change was that the palaces looked rundown instead of elegant. Therefore the duke’s decadence seemed endemic rather than ironic.

A more pointed distinction in this production was the way Rigoletto ran his household. This staging showed him to speak cruelly to his housekeeper Giovanna, giving her reason to hate him. Thus when she allowed the duke to come into the house we saw a motive stronger than merely her choice to accept a bribe.

The clothes of the participants were grungier than the norm, and Kelsey wore a strange tailcoat and a derby that gave him a Charlie Chaplin look, albeit more large in size. He limped, but did not have a hump. Instead he had some sort of rash across his back which Gilda nursed with devotion.

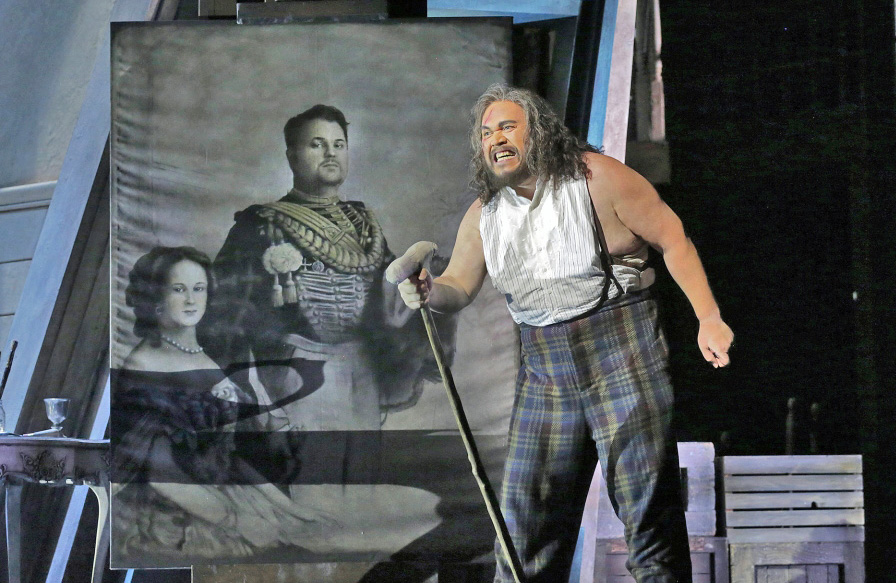

One nice directorial touch was having the furious Rigoletto at the end of Act II tear a portrait of the duke from the wall and slash it to pieces with his knife. The duke deserves this; in Hugo’s text he bragged to Gilda that her father was “my property, my slave.”

But the staging had some infelicities. During the Bella figlia dellâ amore quartet, too much was going on inside Sparafucile’s place. Staff was removing tablecloths and stacking wooden chairs on top of the tables, and that distracted from the singing and acting of the principals.

One could argue whether Sparafucile’s should be shown as a public tavern or a private home as Hugo’s assassin says that he kills his prey “at home” and Verdi’s libretto says it’s “a house half-fallen into ruin” but surely Verdi did not intend for his quartet to fight with the wait staff for attention.

Italian conductor Jader Bignamini set a good pace. He and Kelsey agreed that Rigoletto’s cry of Maledizione be sung as written, without the normally-interpolated high note, in every case until the end of the final scene. Then, when that high note came, the impact was maximized.

Read other reviews on The Cultural Critic