A moment, please, to remember Lorenz Hart. Richard Rodgers’ song-writing partnership with Oscar Hammerstein is better-known. But Rodgers worked with Hart even longer than he worked with Hammerstein, from 1919 to the year of Hart’s death, 1943, while Rodgers’ partnership with Hammerstein lasted from 1943 until Oscar’s death in 1960.

Rodgers wrote more shows and more songs with Hart— 26 shows with Hart versus nine with Hammerstein, and ten original movie musicals with Hart versus one with Hammerstein.

Consider the play list for TV’s “Tonight Show” of January 19, 1956, when Rodgers was Steve Allen’s guest for the entire 90-minute program. 14 of the 17 songs that night were by Hart. Most were chosen by Rodgers extemporaneously as he sat at the piano. Clearly, he was revealing his personal favorites.

It’s easy to see why Rodgers & Hammerstein is a logical choice for big events. The songs are communal and festive —- just what people want to sing when they’re at a clambake, a hoedown or climbing a mountain. Hart’s songs are meant for quiet moments when you’re alone or with one special friend. Singers say that R&Hart provide better cabaret material because their songs are more intimate, while R&Hammerstein are more operatic. Hammerstein ballads build to big, high endings as in “Some Enchanted Evening,” “People Will Say We’re in Love,” “Younger Than Springtime” and “No Other Love.” Hart’s ballads are quieter, like “My Romance” and “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was.”

Orchestrator Bruce Pohamac points out that Rodgers, when writing with Hammerstein, had lyrics in front of him, so he knew that he was composing for the emotional climax of the scene and therefore wrote big endings. (In his collaboration with Hart, Rodgers composed the melodies before the words were written.)

Another explanation is the social environment. The most popular singers in the Rodgers & Hammerstein era— Perry Como, Billy Eckstine, Eddie Fisher— belted loud, high endings to many of their songs. In the Rodgers & Hart era, Bing Crosby, Russ Colombo and Rudy Vallee crooned more softly. The question is: who was responding to whom? Did the pop singers take their cue from what was happening on Broadway, or was it the other way around? Or was everyone in the late-1940s— composers and pop singers alike— responding to a triumphant, almost bombastic national mood that said, “We won the war, and we can achieve anything we want!”

Cabaret impresario Donald Smith said that audiences appreciate Hart songs “because they’re timeless, as long as people fall in love and out of love. Hart combined wit with a marvelous romantic view. It’s sad that you don’t hear his music on radio as we used to, but nightly, in small rooms, cabaret singers keep this repertoire alive.”

Jazz singer Stacey Kent says: “The songs still feel fresh. They might as well have been written yesterday.” Vocalist Mary Cleere Haran says that the young Rodgers wrote “innocent, other-worldly melodies, while Hart wrote irreverent, sarcastic words and the clash between the two styles made the songs interesting.” Dave Frishberg, the pianist-singer-composer, says that jazz players love Hart’s songs because Rodgers set them with ambiguous harmonies that can go in all sorts of different directions. “You can’t do that with Arlen melodies, and you can’t do it with Rodgers & Hammerstein songs. If you try to change them they don’t sound right,” Frishberg told Terry Gross, the host of public radio’s “Fresh Air.”

Mary Rodgers, herself a successful composer, described how her father’s work was different when he was with Hart: “Daddy and Larry were young, they had nothing to lose, and they took more chances.” David Loud, music director for the 2002 production of The Boys From Syracuse, says: “There’s a pep and a fizzy joy in the songs he wrote with Hart, a sense of surprise in the up-tunes and heartbreaking irony in the ballads that is very different from the music he wrote for Hammerstein’s lyrics. Hart’s lyrics are so witty and naughty; he finds so many ways to write about sex without ever being dirty — and yet so poignant.”

Hart brought out Rodgers’ mischievousness, while the Hammerstein years brought out Rodgers’ nobility. Rodgers & Hart songs are fun, while Rodgers & Hammerstein songs are inspiring.

I’d like to describe how the two partnerships have impacted this listener. Growing up, both genres moved me, but in disparate ways. As a child I could tell one difference. Rodgers with Hammerstein wrote hits; Rodgers with Hart wrote standards, that is, perennials. Of course, many of the Hart songs were hits when they were new, but that was before my time. All I knew was that those songs seemed as if they’d been around forever, and therefore would go on living forever, timelessly. Conversely, “People Will Say We’re in Love” was the hot new tune of the year and it rose, then fell off of, the charts. Like everything on pop charts, it seemed disposable. This distinction may be mistaken, but that’s how it seemed from my childish perspective. By the way, I loved the way the young Frank Sinatra sang “People Will Say We’re in Love” even though I resented that the girls in my school swooned for Sinatra and wouldn’t give me or my male classmates the same attention.

When “People Will Say We’re in Love” (in 1943) and “If I Loved You” (in 1945) became number one on the Hit Parade, the announcers always identified them with their specific Broadway shows. But Hart’s “Where or When” and “Blue Moon” and “Lover” and “It’s Easy to Remember” transcended year, singer or show (in fact “Lover” and “It’s Easy to Remember” came from movies, not shows, and “Blue Moon” came from neither.) When you thought of these songs you connected them with the people in your own life, your family, your friends, not with a play on the Great White Way. So I loved both Hart’s and Hammerstein’s songs, but differently.

As I reached adolescence, the separate identities of the two collaborations collided. In the spring of 1949 the MGM film biography of Rodgers & Hart, Words and Music, opened in movie houses, followed by the premiere of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s South Pacific on the stage of the Majestic in New York. I was thrilled to hear all the R&Hart songs in the movie, was turned on by the dancing of Gene Kelly and Vera Ellen to the lush music of “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue,” and I was moved by the sadness of Larry Hart’s life.

At the opening night of the Connecticut Yankee revival, November 17, 1943, in New York, a drunk Hart began to sing along with Segal as she performed “To Keep My Love Alive.” Hart was kicked out of the theater. It was a cold, rainy night, Hart was without his overcoat. He contracted pneumonia and died on November 22 at the age of 48.

I wasn’t the only teenager who loved Rodgers & Hart. Perry Como’s records of “Blue Room” and “With a Song in My Heart” and Mel Torme’s disc of “Blue Moon” were among the most popular that spring. My friends and I bought 78s of the instrumental “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue,” conducted by Lennie Hayton on the yellow-and-black MGM label, and played it incessantly.

Then came the opening of South Pacific, hailed as one of the great stage musicals of all time, dramatically and musically more advanced than Oklahoma! and more accessible than Carousel. No less than four of South Pacific’s songs got into the top seven of Your Hit Parade. (Why did they play the top seven, rather than the top eight or ten? Because Lucky Strike cigarettes sponsored the program and called its play-list the “Lucky seven” songs of the week.) Those hits were “Some Enchanted Evening,” which was number one for nine straight weeks, “Bali Ha’i,” “A Wonderful Guy” and “Younger Than Springtime.”

Disc jockeys didn’t play only those favorites. They played all of South Pacific’s score, even the overture from the cast album. When the public clamored for more, Columbia issued Mary Martin singing a ballad that was cut from the show before it opened, “My Girl Back Home” and Ezio Pinza singing Bloody Mary’s song, “Bali Ha’i.” Variety‘s list of top records showed that there were six separate singles of “Some Enchanted Evening” simultaneously in the Top 50. Versions by Perry Como, Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Ezio Pinza, Jo Stafford and Stuart Foster each were big sellers throughout the summer of ‘49. And there were three different versions of “Bali Hai” and two of “A Wonderful Guy” all in the Top 50 at that same time.

Magazine and newspaper articles discussed the unusual age difference in the romance of Emile de Becque and Nellie Forbush, and the chemistry of Ezio Pinza and Mary Martin in those roles. Ads featured Martin using Prell shampoo to wash that man out of her hair and Pinza puffing cigarettes to connote sexiness. Men wore Pinza neckties and women wore Mary Martin scarves and “South Pacific” lipstick. A magazine article from early 1950, which I saved, says it was “the most fabulous hit in show-business history” and that was not hyperbole. This show got more hype than anything before or since, at least until Hamilton. We’ll never again see a show so simultaneously popular among kids, the working-class public and Broadway aficionados. I fell in love with it too, despite my affection for Rodgers & Hart.

As a writer for my high school newspaper, I made a survey of the songs most-whistled in the hallways during the 1949-50 school year, and “Some Enchanted Evening” was the winner by a huge margin. The song unleashed such feelings of romantic hope among us adolescents! Andrea Marcovicci later told me that “Some Enchanted Evening” was “the song that fucked me up more than any other, giving me the false expectation that finding love would be magical and easy.”

When Mayor William O’Dwyer of New York ran for election while dating a woman half his age, he won. When asked if he would marry her after the election, he replied by whistling “Some Enchanted Evening.” Every man of that era wanted to be Ezio Pinza, and every woman Mary Martin.

The show captured the psyches of another demographic group, too. My uncle Gil Engel had served in the South Pacific, and he came over to our house, sat on the back porch listening to our album and said how perfectly it captured the feelings he had during the war.

As South Pacific became an institution, so did its creators. The two of them now were more stately and regal, and so was their music. Rodgers developed richer harmonies, his melodic cadences became less playful and more hymnal. In the years after Hammerstein’s death, his shows with Rodgers started to be criticized for being too optimistic and endorsing America’s post-war complacency. But the authors didn’t intend that. Only in hindsight does it appear as if their shows endorsed Eisenhower’s agenda. Ike supported the addition of “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance around the same time that Rodgers & Hammerstein songs started being used as patriotic anthems.

But Rodgers and Hammerstein were political liberals. They supported the presidential candidacy of Adlai Stevenson against Dwight Eisenhower. They advocated civil rights and tolerance for people “whose skin is a different shade.” Now we might say that they didn’t go far enough. Most of their shows avoided problems in American society and dwelled, instead, on far off times and places.

Leonard Bernstein reacted to that. On television’s Omnibus in 1956, Bernstein said that most American musicals were similar to European operetta in their reliance on exoticism and happy endings. Rodgers & Hammerstein’s musicals were operettas, he claimed, because they were set in far away times or locales. Even South Pacific, written in 1949 about a war that ended only four years earlier, was an old fashioned operetta according to Bernstein, because it was set half-a-world away. He, Bernstein, was going to change everything by writing a musical set in New York in our own time, a tragedy about American life. This, of course, became his West Side Story.

About Rodgers & Hart shows, Lenny said not a word. That could be because they were usually set in the here and now, and therefore have immediacy. Or, more likely, Bernstein considered Rodgers & Hart shows to be disposable pieces of fluff. After Oklahoma!, that’s what critics said about almost everything written earlier.

What they put on stage should not be casually dismissed. I enjoyed seeing productions of almost all the Rodgers & Hart works which they wrote after their return from Hollywood to New York in 1935 (in later revivals, of course), and I could see how they stretched the bounds of Broadway musicals. Jumbo took place in a circus ring, On Your Toes was the story of ballet dancers, Babes in Arms was about the emergence of a youth culture and social unrest during the Depression, The Boys From Syracuse modernized Shakespeare, I’d Rather Be Right spoofed President Roosevelt, and By Jupiter foretold women’s lib. But none of the Hart shows are great drama except for Pal Joey, with its caustic book about the seamy side of show biz.

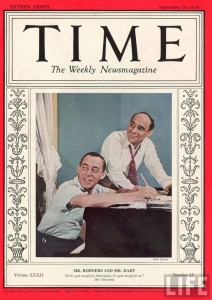

Rodgers & Hart’s innovative stage works caused them to be hailed in the 1930s as America’s Gilbert & Sullivan— as in the lead article in Time magazine, pictured here. After Rodgers & Hammerstein made everything earlier seem lightweight, the songs of Rodgers & Hart remain heavyweight champs. The excellent numbers they composed for the movies, Love Me Tonight, Mississippi, Hallelujah I’m a Bum, Hollywood Party, Manhattan Melodrama, Evergreen, The Phantom President and Nana live on, even though most of those films are forgotten.

As a pre-teen I saw the road company of Oklahoma! and, starting with South Pacific, I went to see every Rodgers show early in their New York runs, and I Remember Mama in its Philly try-out. I bow to no one in my enthusiasm for Rodgers & Hammerstein, but I never lost my affection for Hart.

I haven’t even mentioned until now another facet. In contrast to the optimism of Rodgers & Hammerstein, Rodgers & Hart shifted between major and minor. Hart’s lyrics rhapsodized about love in “My Heart Stood Still, “My Romance” and “With a Song in My Heart.” Then he wrote about heartbreak and loneliness in songs like “Glad to Be Unhappy,” “Little Girl Blue” and “Spring is Here.” Hart was under five feet in height and thought he was ugly. He was a troubled gay man and alcoholic who wrote sublimely about unhappiness. But we shouldn’t think of him as only a writer of sad songs.

Marin Mazzie, with Stephen Flaherty at the piano, sang “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” at a Rodgers centennial concert, celebrating and complaining about an obsessive romance. Join that with the six songs I just mentioned as quintessential classics to be performed as often as possible. Add to them these examples of disillusion: “Falling in Love With Love (is falling for make believe)” “You Are Too Beautiful (for one man alone)” “Nobody’s Heart (belongs to me)” “Ten Cents a Dance,” “He Was Too Good To Me,” “It’s Easy To Remember,” “It Never Entered My Mind” and “A Ship Without a Sail.”

Then look at these Hart songs which are basically happy, although sometimes in minor keys with unexpected dissonance: “Blue Moon,” “You Have Cast Your Shadow on the Sea,” “The Shortest Day of the Year,” “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” “My Funny Valentine,” “Here in My Arms,” “I Could Write a Book,” “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World,” “Dancing on the Ceiling,” “You’re Nearer,” “There’s a Small Hotel,” “Lover” and “Isn’t It Romantic?” Notice that this hopeful list is much longer than the sad one.

And then there are the happy, clever, up-tempo Rodgers & Hart numbers like “Manhattan” and “Mountain Greenery.” And, finally, that ambiguous masterpiece, “Where or When.” Did they really meet before? And love before? Is it a fantasy, believed by the character who sings it? Or a pick-up line? Or an intimation of past lives and immortality? “Where or When” contains a sublime progression of passion, when Hart takes us, step-by-step, from “we have met before” to “and laughed before and loved before”— all in virtually one breath.

Though disillusioned, Hart still is obviously in love with love, although, for him, it’s make believe. Hart was a sophisticate and an intellectual, but many of his lyrics are remarkably simple. Two of his best songs are almost all one-syllable words: “My Heart Stood Still”— “I took one look at you / That’s all I meant to do / And then my heart stood still”— and “With a Song in My Heart”— “Just a song at the start / And it soon is a hymn to your grace/…But I always knew / I would live life through / With a song in my heart for you.”

Gary Stevens, a former Broadway columnist, said: “Oscar Hammerstein wrote for fifty states and Larry Hart wrote for five guys at Sardi’s.” That’s a great putdown, but plenty of people from small towns appreciate Hart too.

Another critic is Stephen Sondheim who faults Hart for the inexactitude of his rhymes. Sure, Hart did reach for tricky multiple rhymes for the sake of cleverness, but he seemed to be winking at the listener when he slipped in a bad one.

It would be fair to say that Hart’s lyrics ask for a high level of cultural literacy. For example: “I’m dumb again / And numb again / Like Fanny Brice singing `Mon Homme’ again.” How many people know Brice’s 1920 hit, “My Man,” and the fact that it was adapted from a French song called “Mon Homme”? But look at Sondheim’s “I’m Still Here” and its even-more-obscure reference to the Beebe Bathosphere, which was part of the 1939 Worlds Fair. The cool thing about Hart is that his songs are fun. Touching, and fun.

Michael Flaherty, resident music director at Goodspeed, said that Babes in Arms presented a challenge. “We wanted to do the show because it has such a great score, but Hart’s lyrics are so sophisticated that they don’t seem to fit the young characters. Our new version of the book makes it clear that these are kids of show biz parents, so they have a more worldly background than most people of their age.” Flaherty believes the original orchestrations also are too adult, and Goodspeed used new ones that were “kickier, jazzier, no strings, like Benny Goodman in the 1930s.”

Rodgers’ melodies in those days took a cue from Hart’s art, and they are not as innocent as most listeners, like Haran, might think. They are full of surprises. He is hypnotically simple, as in the repeated three-note figures at the opening of “My Romance” and on the words “the most beautiful girl in the world” and “I’m wild again, beguiled again, a whimpering, simpering child again.” Listen to the repetition of single notes on “your sweet expression, the smile you gave me” and “sit there and count your fingers” and “it seems we stood and talked like this before” and “lover, when I’m near you and I hear you” and “falling in love with love.”

Then, with a jolt, he’ll insert an unexpected tone. Rodgers played tricks by taking a melody “where you don’t feel it will go; not the notes for which the preceding phrase has prepared you,” to use a description by Rodgers & Hammerstein executive Ted Chapin. Rodgers tends to throw in a diminished note, or a flatted note, half-a-tone down from what you anticipate. Other times Rodgers will make an unexpected upward leap as in “you make me smile with my heart” and “falling in love with love is playing the fool” and “seem to be ha-ppening again.” These became Rodgers & Hart trademarks. Orchestrator Don Walker lovingly called the man “wrong-note Rodgers.”

Those unusual notes stick in listeners’ minds. They are what makes Rodgers’ music memorable. Rodgers continued to use creative melodic choices throughout his career, but not as often as when he worked with Hart. He used strikingly “wrong” notes in the verse of “The Sound of Music,” for example, but after Hart’s death, his priority was reassurance rather than surprise.

I never get tired of hearing Rodgers & Hammerstein, and there’s much beauty in Rodgers’ work with different lyricists after Hammerstein’s death. But that isn’t all there is. There’s so much more to celebrate.

*

As an addendum, here’s a list of Rodgers & Hart recordings to treasure:

Richard Rodgers Centennial Celebration: The Sound of His Music (DRG)

The majority of the 21 songs are by Hart, and the performances are choice, including live club appearances and vintage numbers by Lena Horne, Elaine Stritch, Eartha Kitt and Josephine Baker.

Mary Martin Sings, Richard Rodgers Plays (RCA Victor)

Although she was never in a Hart show, Martin chose to make 8 of these 12 selections by Hart instead of Hammerstein. This 1957 recording includes two lovely rarities, “Sleepy Head” and “Moon Of My Delight.” She’s in excellent voice, but she ruins the point of “To Keep My Love Alive” when she changes the deliberately discordant ending that Rodgers wrote. The composer’s piano collaboration is lilting but too brief. Most of the time Martin is backed by a full orchestra with Robert Russell Bennett arrangements.

Dawn Upshaw: Rodgers & Hart (Nonesuch)

Upshaw sounds charming. Her emphasis is on clarity and musical values more than deep emotions. “A Ship Without a Sail” and “Ev’ry Sunday Afternoon” are outstanding, and Audra McDonald joins Upshaw on the rare “Why Can’t I?”

This Funny World: Mary Cleere Haran Sings Lyrics by Hart (Fynsworth Alley)

You need to hear this in a quiet room, as her interpretations are soft and breathy. Haran includes some rarities. “Everybody Loves You” is beautiful and is backed by Richard Rodney Bennett’s interesting combo.

Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Rodgers & Hart Songbook (Verve)

When you talk about “straight-ahead” jazz, use this as illustration. Clean, no tricks, perfect intonation and soulful, deeply-felt interpretations of the material.

With a Song in My Heart (Centaur)

Skitch Henderson conducted his New York Pops Orchestra and Maureen McGovern in a nice program where 10 of the songs are by Hart. It brings back memories of that “Tonight Show” in 1956 when the vocals were by Steve Lawrence, Eydie Gorme, Andy Williams and Pat Kirby. Does anyone have a tape of that— even just the audio?

In Love Again – Stacey Kent (Candid)

A great all-Hart collection from a new jazz star, a New Yorker who recorded in London. She’s particularly creative with meter and time values, giving the songs a playfulness that surely would please Larry Hart. The five-man instrumental combo contributes equally fresh sounds.

Rodgers & Hart Revisited (Painted Smiles)

If you can find Volume 2 of this title, it’s worth buying for three tracks on it: Ann Hampton Callaway crooning “It Must Be Love” and “Soft as a Kitten” and Bobby Short singing “From Another World.” The songs and those performances are stunning.

Dearest Enemy (Bayview)

Richard Day-Lewis and a British cast re-creating Rodgers & Hart’s first book show, from 1925. “Here in My Arms” is a break-through, their first romantic ballad.

Hollywood Party (Bayview)

Rodgers & Hart wrote a score for a 1934 MGM film that was shelved. Their unused songs turned up in 1981 and were put on disc by young singers for Beginners Productions, released on CD by Bayview in 2001. Listen to the gorgeous “My Friend, the Night” and an early version of what was to become “Blue Moon,” titled “Prayer.”

On Your Toes (Polydor)

This was the third recording of the score. A 1951 Columbia album with Jack Cassidy and Portia Nelson impressed listeners so much that the show was revived with Bobby Van, Elaine Stritch and ballerina Vera Zorina with new orchestrations by Don Walker, which also was recorded. The 1983 Broadway revival used Hans Spialek’s original and colorful 1936 orchestration. The cast included Christine Andreas, Dina Merrill, Lara Teeter and George S. Irving.

Babes in Arms (New World Records)

Evans Haile conducted a concert version of this classic score in 1989 with the original Hans Spialek orchestrations from 1937. The fine cast, including Judy Blazer, Gregg Edelman, Jason Graae and Judy Kaye, made this almost-complete recording featuring “Where or When,””My Funny Valentine” and “The Lady Is a Tramp.”

Babes in Arms (DRG)

Rob Fisher conducts an Encores production of this show from 1999. He and his youthful cast are even better than the CD from New World. An ardent David Campbell makes “Where or When” sound as if it’s never been heard before. The music is more complete, spoken intros are included in many scenes, and Fisher’s orchestra sounds like a real pit band.

The Boys From Syracuse (Sony)

Portia Nelson and Jack Cassidy are the creamy-voiced singers who introduced this score to a new generation of listeners in 1953. Nelson later became a song-writer and cabaret performer; here she’s an ingenue who sounds something like Marin Mazzie on “Falling in Love With Love.” Lehman Engel conducted with good theatrical effect, but the plucked strings in the uncredited orchestration sound closer to David Rose than to Broadway.

The Boys From Syracuse (DRG)

An Encores! production, led by Rob Fisher, using the original 1938 orchestral charts, with Rebecca Luker, Debbie Gravitte, Davis Gaines, Malcolm Gets. This is far more complete, and the performances are bright and fun-packed. If you’re buying just one Syracuse, this should be it.

The Boys From Syracuse (Decca)

Since the characters are supposed to be ancient Greeks, a Broadway sound isn’t needed, and you won’t be put off by the accents in this 1963 British revival. If Brits tried to do Babes in Arms it would be a different matter. The most interesting things on this CD are the arrangements by the great Ralph Burns, just when he was switching gears from the big bands to musical theater, and some of his work here is a bit too brassy. An added attraction: recordings of six songs from the show by Rudy Vallee and Frances Langford made in 1937.

Pal Joey (Sony)

Written three years after The Boys From Syracuse, with Europe now at war and Hart more ill, this is the darkest, grittiest Rodgers & Hart play. This 1950 studio recording led to a stage revival. Vivienne Segal created the role in 1940, repeated it here and in the revival. It’s good to have this documentation of the older woman who beds a cocky hoofer played by Harold Lang, but he doesn’t sound nasty enough. Lehman Engel conducts watered-down approximations of the original orchestrations.

Pal Joey (DRG)

Rob Fisher conducting the Encores production from 1995 starring Patti LuPone, Peter Gallagher and Bebe Neuwirth. All three are excellent and LuPone especially so as the world-weary but sexy Vera. The original orchestrations were unearthed just before this recording was to begin, and Fisher’s band makes them sound biting and jazzy.

A Connecticut Yankee (Decca)

One of Rodgers & Hart’s earliest hits was revised in 1943 with some newly-written songs. Hart died a week after the revival opened, at age 48. Vivienne Segal’s almost-seven-minute version of Hart’s last song, “To Keep My Love Alive,” is a stunning performance. These original cast recordings by the 1943 cast are augmented by songs from Rodgers & Hart’s Higher and Higher and By Jupiter, recorded in 1940 and 1942 by two of the stars of that era, Shirley Ross and Hildegarde.

Wall to Wall Richard Rodgers (Fynsworth Alley)

This selection from an all-day marathon concert contains 11 Hart tracks. Judy Kaye, Mary Cleere Haran (singing out more than on her solo disk) and James Naughton are the most impressive artists. A few performers inexplicably appear more than once while some outstanding performances from that day are omitted.

For other stories of songwriters, click here.