Among all hard-luck classical composers, the ones most-often cited are Mozart and Mahler. The former was a social misfit and died at age 35 in poverty. The latter had heart problems, suffered anti-Semitism and an unfaithful wife, and died prematurely.

Yet I submit the toughest life was that of Dmitri Shostakovich. During the Communist purges of the 1930s he was denounced by his nation’s dictator, Josef Stalin. He was questioned about his acquaintances, asked to “name names” — almost like the McCarthy era in the USA in the 1950s, but with much higher risk. Many of Shostakovich’s friends were arrested, exiled and killed. Being an internationally-respected artist did not exempt him from such a fate.

Shostakovitch’s first three symphonies were popular, and were patriotic. The Second was titled “To October” (celebrating the Revolution) and Third was called “The First of May” (International Workers’ Day). Then, in 1936, when he was 30 years old, Shostakovich observed Stalin’s harsh crackdown against his political opponents. That’s when he composed his Symphony No. 4 in C minor, a daringly modern presentation of dissonances, sardonic irony and dark moods. This music reflects his disillusionment and pessimism.

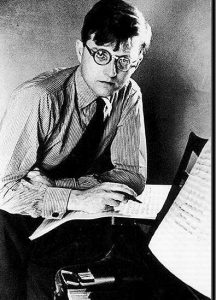

To the right, Shostakovich around 1930:

He was informed by the government that the premiere performance was being cancelled and he was forced to announce that this was his voluntary decision.

To rehabilitate himself, and to save his family from retribution, he wrote an affirmative Symphony No. 5 with a triumphant march at the end. He allowed it to be described as “a Soviet artist’s creative answer to just criticism.”

Shostakovich lived in continual fear for the next 25 years. He outwardly conformed to government policies and put his name to articles expressing the government line. He wrote his Seventh Symphony, the “Leningrad,” while Russia resisted the Nazi invasion yet he confided to his friends that he meant it as a rebuke of Stalin more than of Hitler. Soviet officials criticized his Eighth (in 1943) as dark and defeatist, and his Ninth (in 1945) as trivial.

Shostakovich was denounced again as being unpatriotic in 1948, and his friends reported that he was anxious about his safety. Leopold Stokowski met with the composer and observed that a Soviet security man constantly trailed Shostakovitch, whom he described as “extremely melancholy.” Composer Krzysztof Meyer said that Shostakovich’s “face was a bag of tics and grimaces.” Writer Mikhail Zoshchenko described Shostkovich as “frail, fragile, withdrawn.” The pianist Sviatoslav Richter wrote in his notebook that Shostakovich “was consumed by irritability.”

The Symphony No. 4 was never performed until 1961, after the death of Stalin. Shostakovich had opportunity to revise it but, instead, left the score exactly the same as in 1936. Clearly, he wanted to present it as his testament. Since then, because of its size and complexity, the symphony has not received frequent performances.

Yannick Nézet-Séguin believes that it’s a masterpiece, and his rendition with the Philadelphia Orchestra strongly makes that case. This is a monumental work that, til now, has not been sufficiently appreciated.

Shostakovitch apparently believed what Mahler had stated as his objective: to include the entire world within his music. The Symphony No. 4 is very long, and jammed with folk tunes, dances and marches. A wide variety of instruments have solo passages, and the composer experimented with odd combinations of instruments.

Yannick led 110 players, including eight French horns, and multiple tympani, cymbals, woodblocks, xylophone and glockenspiel. The music is intentionally grandiose and bombastic because Shostakovitch meant to satirize the grandiosity and bombast of the Stalin regime. He foresaw a tragic outcome for his country, and expressed that in this music. It starts with a march, but whenever a phrase leads up to what should be a triumphant tone, instead we hear sharp dissonance.

Don’t think that the symphony is an unkempt mess of unsorted ideas. To the contrary, Shostakovich wrote a tightly-organized rapid fugue in the middle of the first movement, and the Philadelphia strings played it with spectacular energy.

The finale includes a funereal Largo and an Allegro filled with grotesque dances and marches. After a monstrously loud climax the music subsides to a soft celesta leading into a quiet, dissonant and haunting conclusion.

It’s appropriate for Nezet-Seguin to take up the cause of Shostakovich, because the Philadelphia Orchestra has been closely connected to the composer’s work. Stokowski led the American premieres of Shostakovich’s First, Third, Sixth, Eleventh, and Twelfth symphonies, and Eugene Ormandy led the American premiere of this Fourth.

In smart programming, Yannick filled out this concert with a piano concerto by Sergei Prokofiev, who also kept one piece unperformed for many years. It was this Piano Concerto No. 2, played here with Yefim Bronfman as soloist.

Started in 1912 during the czarist regime, the concerto perished in a fire following the Russian Revolution. Prokofiev reconstructed the work in 1923. Starting with a deceptively soft and lyrical piano solo, the concerto turns into a pounding example of virtuosity (marked tumultuoso). It remains one of the most technically formidable piano concertos in the repertoire. Prokofiev biographer David Nice referred to two of the world’s best pianists in 2011 and claimed that “Argerich wouldn’t touch it, Kissin delayed learning it.”

Bronfman started with classical restraint, which made his exuberant climaxes seem all the more impressive.

Please share your thoughts with us. Address to editor@theculturalcritic.com

Read other reviews on The Cultural Critic