The music world thinks of Sammy Cahn & Jule Styne as a team. The songwriters burst on public consciousness with a string of hits in the 1940s, and both remained in the limelight till their deaths — Cahn in 1993 at age 79, Styne in 1994 at 88. But they wrote only two Broadway shows together and essentially stopped working as a team at the end of their first decade.

Their big hit on stage was High Button Shoes in 1947. Then Styne found a new collaborator for his next show, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, in 1949. Styne went on to compose scores for 17 more shows without Cahn: Two on the Aisle, Hazel Flagg, Peter Pan, Bells Are Ringing, Gypsy, Say Darling, Do Re Mi, Funny Girl, Fade In-Fade Out, Hallelujah Baby, Subways Are For Sleeping, Darling of the Day, Prettybelle, Sugar, Lorelei, One Night Stand and The Red Shoes. Cahn, meanwhile, continued to write pop hits and motion picture scores. The two remained friends, so they said, and they worked together on the musical Look to the Lilies in 1970. But nothing was the same after 1948.

What went wrong? Based on conversations I had with Cahn and with Styne, plus reading Styne’s autobiography, “Jule,” and Cahn’s autobiography, “I Should Care,” here’s the story:

You couldn’t find a songwriting duo more similar in background and personality. Maybe that’s the heart of the problem right there. Look at the differences between Gilbert & Sullivan, Rodgers & Hart and Lerner & Loewe, all of whom had friction and stayed together a long time. In any event, Jule Styne got irritated with conduct by Cahn that was remarkably similar to Styne’s own behavior.

Julius Stein was born in a poor section of London in 1905 and grew up in Chicago. He studied piano and played it well enough to have a classical career. But he was a hustler and promoter who preferred a different lifestyle, getting jobs in burlesque houses, with dance bands and eventually at Hollywood movie studios. He had a brilliant mind, spoke rapidly and often changed subjects abruptly, leaving his friends to wonder what he was talking about. Along the way he changed the spelling of his name to Jule Styne to avoid confusion with a neighbor named Julius Stein who became the head of Music Corporation of America. He always was addressed as “Julie.”

Samuel Cohen was born in 1913 and raised in the poor, Lower East Side of Manhattan. He described himself as a brazen, mischievous boy who hustled, promoted himself and became a lyric-writer on Tin Pan Alley. Through friends in the record business, the extroverted Cahn eventually talked his way into a lyric-writing job at Republic Studios in Hollywood. He changed his last name because it sounded too Jewish, thinking that Cahn might possibly be considered a gentile German name by potential employers. He even convinced his first composing partner, Saul Kaplan, to change his name to Saul Chaplin for the same reason. Sammy told Saul that Cohen and Kaplan sounded like the name of a garment firm. To everyone who ever met him, however, Sammy certainly was Jewish. His conversation was sprinkled with Yiddish, and he gave his children religious education.

Both men were prolific writers and loved to sing their own songs. Sammy said: “I literally can’t keep my mouth shut when it comes to selling my own material.” Both men were assertive, even brash, in promoting themselves. Cahn tells this story on himself: “The first time I ever sang to Bing Crosby he said, `You’re pretty good.’ I said, to keep up the image, `Pretty good? I’m the best!'”

Jule Styne would come to his colleagues with a new song and introduce it thusly: “May I say? Another classic.”

Cahn and Styne were paired together in 1942 for a movie at Republic and at the start Styne was angry. He had been working with Frank Loesser — already a respected lyricist, although not yet known for his music — and Styne and Loesser wrote the hit, “I Don’t Want to Walk Without You.” From this perspective, Styne considered Cahn to be a step down. He also told friends and wrote in his autobiography that Cahn possessed no musical education and didn’t play an instrument.

Styne was mistaken on two counts. In fact, Cahn played the violin when he was a kid and then learned piano, and Cahn’s writing credentials were as legitimate as Loesser’s. Loesser was responsible for “Two Sleepy People” and “Heart and Soul” but Cahn had penned “Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen” and “Please Be Kind.” Nevertheless, Cahn projected a commonness, a lack of polish, and Styne clearly wanted to associate with someone who seemed classier.

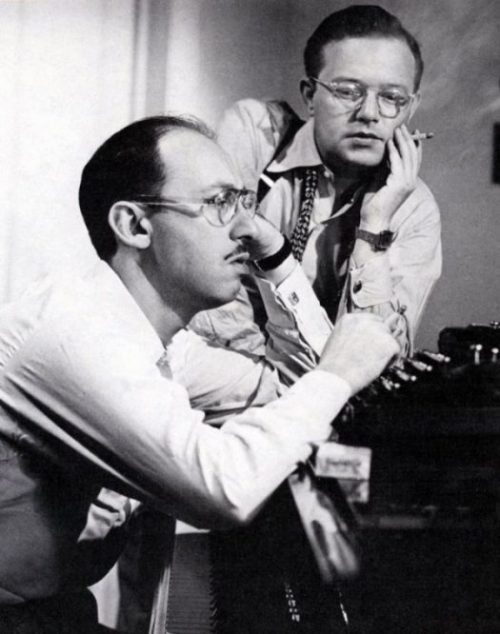

Styne’s manner and his accent, mind you, weren’t any classier than Cahn’s. But Jule wanted to rise above his beginnings. Later on he had a romantic relationship with a world-traveling socialite, then he married a British actress. Cahn, even when he became rich, still seemed heimische. [See photo of Cahn on the right]

Cahn described his first working session with Styne: “He went to the piano and played a complete melody. I listened and said ‘Would you play it again, just a bit slower?’ He played and I listened. I then said, ‘I’ve heard that song before’—to which he said, bristling, ‘What the hell are you, a tune detective?’ ‘No,’ I said, ‘that wasn’t a criticism, it was a title.'” “I’ve Heard That Song Before” became their first hit.

After working on one film, Styne parted ways with Cahn. According to Sammy: “He was done with me. He dropped me, bang, like that. Jule went on to do another score with Kim Gannon. Then he left Gannon and went on to Harold Adamson and then Herb Magidson” with whom Styne wrote “Down Mexico Way.”

After the earlier, initial Cahn-Styne song, “I’ve Heard That Song Before,” became number one on the charts, they got back together to write more. Cahn took the initiative in their partnership. He suggested catchy, topical titles like “It’s Been a Long, Long Time” (about couples re-uniting when the guys came home from World War II) and the two men became famous together. “I’ll Walk Alone” and “There Goes That Song Again” became wartime best-sellers because of Cahn’s colloquial lyrics and Styne’s easy-to-hum melodies.

For anyone alive in the 1940s, Cahn & Styne captured the sadness of loved ones separated during the war, and the joy of returning to a peaceful land after the war.

A series of romantic ballads – “It’s the Same Old Dream,” “Give Me Five Minutes More,” “The Things We Did Last Summer,” “Saturday Night Is the Loneliest Night of the Week,” “Let It Snow,” “Time After Time” and “It’s Magic” — kept them at the top of their profession during the postwar years.

Cahn described how he and Styne wrote “Let It Snow.” “It was one of the hottest days in the history of Long Angeles. I asked Jule ‘Why don’t we drive to the beach to cool off?’ He said ‘Why don’t we stay here and write a winter song?'” They imagined a man and a woman cozy by the fire, eating popcorn, staring out the window watching the snowflakes fall and thinking “Let it Snow! Let it Snow! Let it Snow!”

The writing of “Time After Time” illustrates Styne’s bravado. It was the autumn of 1945 and the theater community was abuzz because Jerome Kern was about to return to Broadway to write the music for the upcoming Annie Get Your Gun. Styne was at a party where the guests wanted to know what Jule had heard about the new Kern show, and Jule wanted to show off. So he pretended that he knew one of the songs, and he told the party-goers that it sounded “something like this.” He then sat at the piano and, on the spur of the moment, made up a melody with an extremely long, spun-out theme that was a good imitation of the Kern style. It later became a Styne-Cahn hit, with that melody unfolding to the words “Time after time I tell myself that I’m so lucky to be loved by you…”

Kern collapsed and died of a stroke in November of 1945 before submitting any songs for Annie Get Your Gun. Neither Styne nor anyone else ever heard any song that Kern wrote for that project. (Photo of Styne is above.)

Styne was able to write a melody that sounded similar to Kern’s best work, and at other times he could compose Viennese waltzes that recalled Johann Strauss and Sigmund Romberg. He was a knowledgeable musician with a wide range of talent.

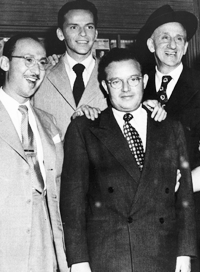

Styne and Cahn hooked up with Sinatra for the film Step Lively in 1943, and both of the boys became part of the Sinatra entourage. They were constantly at Sinatra parties and even traveled with Frankie when he went on tour. Both Cahn and Styne behaved like Sinatra acolytes. Especially Sammy. Someone who made a later trip with Cahn told me that he talked exactly like Sinatra, complete with womanizing crudities.

On the right, Cahn, Sinatra, Styne & Jimmy Durante:

Styne married young. His autobiography implies that he had affairs, but he wasn’t as sexually active as Cahn, who bragged about his many triumphs. (Sammy didn’t marry until 1945, was single again from 1964 to 1970, then remarried, very happily.) Styne’s addiction wasn’t sex, but gambling. He placed bets every day on horse races around the country and ran up huge debts to bookies. According to Sammy: “He was the Married Man and I was the Swinger. I was the sort of fellow who at times had the chutzpah to propose bed before dinner to a date. I got my face slapped quite a lot — and quite a lot I didn’t.”

In his work, Cahn was serially monogamous. He worked exclusively with Chaplin from 1929 till they broke up in 1941 and after that Cahn considered Styne to be his exclusive partner. But Styne’s attitude was more independent. Cahn sounded upset when he told me how Styne accepted jobs with other lyricists even during their years of writing together.

Sammy and Jule wrote a stage musical in 1943, but it closed after tryouts in Philadelphia and Boston. Glad to See Ya! is remembered only as the source of their haunting song, “Guess I’ll Hang My Tears Out to Dry.” The show was planned as a vehicle for Sammy’s good friend, Phil Silvers (“Glad to see ya” was his trademark greeting), but his movie studio wouldn’t release him. Lupe Velez, the so-called Mexican spitfire, was to be the female lead, but she committed suicide. Eddie Davis, then Eddie Foy Jr, were inadequate replacements for Silvers, while June Knight replaced Velez. Cahn said it was a terrible show.

Then Cahn & Styne scored a smash hit on Broadway with High Button Shoes, directed by George Abbott with choreography by Jerome Robbins, starring Nanette Fabray and Phil Silvers. Opening in 1947, it included hits like “Papa Won’t You Dance With Me,””You’re My Girl” and “I Still Get Jealous.”

Time magazine said Cahn & Styne were the country’s most successful songwriting team after Rodgers & Hammerstein. The word “after” is ambiguous, and it’s hard to tell if Time meant that Cahn & Styne were number two behind R&H or they were the best chronologically and therefore were R&H’s successors. Either way, it was a compliment. But the popular partnership suddenly ended.

Jule decided in 1949 that he didn’t want to work with Sammy any longer. Just like his breaking up with Sammy after writing their first pop song, Jule again had a success with Sammy and then dumped him. He sought out the older, experienced Leo Robin to be his partner in the creation of his next Broadway show, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. That score included “I’m Just a Girl From Little Rock,” “Bye Bye Baby,” “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” and the waltz, “We’re Just a Kiss Apart.” The show made Carol Channing a star. Milton Rosenstock, the music director who worked with Styne previously, noticed a change in him, a new take-charge attitude: “Before it was always questions. Now it was ‘I want this. I want that.'”

Two years later, Styne composed Two on the Aisle with Betty Comden and Adolph Green, starting a string of six shows with those collaborators. He also partnered with Stephen Sondheim, Bob Merrill and Yip Harburg, showing no sign that he missed Sammy Cahn.

Styne explained that he ended the working relationship because Cahn had a quick temper and big mouth that alienated potential collaborators. Funny, but Styne himself was known for mouthing off before he took the time to think things through. He once said something undiplomatic to Sinatra, and the singer cut Styne from his social circle for years. Styne’s dissatisfaction had to be based on more than that. He aspired to lofty goals, such as producing and directing other people’s shows on Broadway (which he did, starting in 1951) and producing a TV series. He aimed high and was painfully aware that he still had rough edges; maybe he didn’t want Sammy around because Cahn reminded him of his own humble start and his own worst traits.

In Cahn’s autobiography “I Should Care” he says the break-up came when Styne offered him the chance to go back to New York to work on Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and Sammy declined because he wanted to stay with his wife and young children in California. I don’t believe that. It sounds more like Sammy trying to diplomatically save face. Styne’s autobiography does not corroborate Cahn’s story.

While Styne prospered on Broadway, Cahn did memorable work on films with composers such as Vernon Duke, Sammy Fain, Nicholas Brodszky (for several Mario Lanza movies) and Jimmy Van Heusen (for a series of Sinatra classics.) Cahn and Styne did work together once more in Hollywood to write just one song, but it was a big one: the title song for Three Coins in the Fountain in 1954.

Cahn and Van Heusen wrote two musicals that came to Broadway: Skyscraper in 1965 and Walking Happy in 1966. Sammy spoke of Skyscraper as a “devastating experience,” mainly because Julie Harris couldn’t sing. “Each time she sang, I couldn’t help it, I left the theater.” He also wrote, with Van Heusen, the title song for the movie Thoroughly Modern Millie and that song is so memorable that it had to be included in the show by that name that was a Broadway hit in 2002. Cahn also developed an unproduced musical about Bojangles with Charles Strouse.

Cahn and Styne came back together to write the 1970 show Look to the Lilies, based on the movie Lilies of the Field. It was to star Shirley Booth and Sammy Davis Jr in the role made famous in the movie by Sidney Poitier, and was directed by Josh Logan. With this proven story, this talent and songs by Cahn & Styne, how could it miss? Well, it did. Davis wanted too much money and was replaced by Al Freeman Jr, who was weak in the part. This was a sad ending for a partnership once praised as the greatest after Rodgers & Hammerstein.

In 1971 Cahn performed his songs and talked about his career at Maurice Levine’s “Lyrics and Lyricists” series at Manhattan’s 92nd Street Y. A recording of this was issued on the DRG label. Sammy developed this into a revue which he titled Words and Music, performing it around the country and for nine months on Broadway in 1974.

Years later, Styne spoke about Cahn with admiration: “He could write things in a minute. He was incredibly fast. Sammy wanted to stay in action, not sit in creative loneliness like a Loesser or Alan Lerner.”

And, then, Styne’s ultimate compliment: “Even when Sammy had a girl in his arms, he must have been thinking about a lyric.”

For stories of other songwriters, click here.