In 2001 Stephen Schwartz’s career was at a lull. Almost 30 years had passed since he was a wunderkind who had his first three shows running simultaneously on Broadway—Pippin, Godspell and The Magic Show. His mega-hit Wicked still lay ahead.

At this quiet point, Schwartz was content to appear at a luncheon to raise funds for a small theater in the town of Oaklyn in South Jersey. The Ritz Theater was mounting an intimate show in which actors discover a warehouse filled with illusions, and experiment with them. The score was old Schwartz songs.

The composer was happy to drive down from Long Island to sit at an upright piano in a small restaurant across the street from that theater, to play and sing some of his tunes. We, and the others at that luncheon, knew he was an immensely accomplished composer and lyricist. He just happened to be what actors call “between engagements” on the Great White Way.

To be precise, 28 years between engagements! In 1975 his first three shows ended their Broadway runs, and Wicked was not to open until 2003.

(Yes, he wrote other theater pieces in between, like The Baker’s Wife, Rags, Working and Children of Eden, but they were not smash hits.)

We remained in touch when he achieved the biggest success of any Broadway composer in the early years of the 21st century. He invited me to the Wicked recording session, and I also talked with him at the premiere of his opera, Seance on a Wet Afternoon at Lincoln Center, and at the Paper Mill premiere of his stage musical (with Alan Menken) The Hunchback of Notre Dame. But I’d like to travel back to that middle point and observe how he described his life at age 53, before the big resurgence.

So let’s return to 2001.

* * *

Two themes run repeatedly through the songs of Stephen Schwartz. One is magic, the other is family.

Stephen Schwartz has continually, and pointedly, written about parent-child relationships. Consider Pippin and his father Charlemagne in Pippin; Geppetto and his puppet-son, Pinocchio, in the TV musical Geppetto; Judge Frollo, the controlling surrogate father of Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

That’s not all. There’s also Pocahontas and her father in the film Pocahantas. The Biblical families in Children of Eden. And the song “Fathers and Sons” in Working.

And magic has interested him ever since he was a kid. His first show, Pippin, opened with the song “Magic To Do” and another of his early hits was all about the profession, The Magic Show, which ran on Broadway from 1973 to 1975. “When I was in college at Carnegie Mellon,” revealed the boyish-looking, 53-year-old Schwartz, “I wrote the opening of Pippin as a magic trick, showing the Player pulling our scenery out of his hand.”

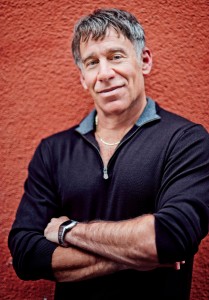

Schwartz still lives near New York City, not far from where he was born, and he keeps an apartment in Manhattan, but he has a distinctly California look. Darkly suntanned, he wears white sneakers even when he’s performing. Returning to his discussion of magic, Schwartz says “I created a show where I could work with Doug Henning—The Magic Show. I was a bit disappointed when I saw the details of how the illusions worked, so I asked him to stop explaining his tricks to me.”

Schwartz also wrote a song called “Prestidigitation” in the 1970s and included it on his solo CD, The Reluctant Pilgrim. “And my next show, Wicked, is about the Wicked Witch of the West, so it too will contain illusions.”

On the subject of magic and family, in the 1980s Stephen bought a magic book for his son, Scott, who then developed a small career as an illusionist during his teen years. “We made shirts for him that said ‘Great Scott.’” Scott became a director (3hree, Jane Eyre, tick tick Boom, Batboy.)

When asked about his preoccupation with father-and-son relationships, Schwartz isn’t as quick with an answer.

“Writers always try to work out their issues,” says the composer-lyricist “and I wish I could tell you a dramatic story about my terrible childhood. But I can’t. I had a happy, suburban middle-class upbringing on Long Island. And my wife and I have good relationships with our children. I’ve never talked much about my private life.” But, since he writes about the subject so often — and since he rarely talks about it — I pressed him for more. Is there a buried secret?

“My parents loved music and they put a record player in my play pen. They often played opera records, and when I was very young I used to say: ‘I want to hear the high lady.’ When I started going to school they gave me a clock radio and I’d wake in the morning to WQXR, New York’s classical station.”

Schwartz’s father was an entrepreneur who started several small businesses and his mother was a Head Start teacher in the public school system. Stephen was born March 6, 1948. He has a younger sister and together they would stage musical shows for their neighbors, starting when he was six or seven. “I browbeat neighborhood kids to play in them, then I charged their parents admission to see them.” One of Stephen’s shows was High Dog, about a dog and his family, for which he wrote a lullaby, which he sang for me.

At age seven he started piano lessons and during his high school years he studied piano and composition at New York’s Juilliard School. His interest was in the classics until two things happened. WQXR played Bernstein’s Overture to Candide and Stephen really liked the piece. And then his parents took him to see Shinbone Alley, which had music written by the Schwartzes’ next-door neighbor, George Kleinsinger. After that, Stephen was in love with theatrical musicals.

He became a drama major at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. “Andy Warhol went there, David Byrd was there when I was, and the artsy types all hung out together. A lot of people went on to big theater and TV careers. As for ‘doing your own thing,’ it was the ’60s and I’m relieved to say that I missed the drug thing by a year; the class after me started that. I started in ’64 and graduated in ’68. Drugs destroyed a lot of people I knew.

“In 1964 my roommate had a Supremes record, and the Motown sound changed my life and my writing. I got very interested in that music, and then the Beach Boys, Burt Bacharach, the Beatles, the Mamas and Papas, Jefferson Airplane, Judy Collins, James Taylor. Before then, I was only interested in classical or show music, and folk music.”

At Carnegie Mellon he met Ron Strauss and together they wrote the student show that later became Pippin. “We were really into the film A Lion in Winter and we thought we’d make sort of a musical version of that story, full of court intrigue. Ron read in a history textbook about the son of Charlemagne, and we decided to add that to the Lion in Winter idea. That was Pippin Pippin”— what they called it at first. “We just liked the sound of his name,” says Schwartz, “but we shortened the title very early in the process.”

It was the most successful of the several shows that Schwartz wrote during his college years. So, after graduation in 1968, he moved to New York and started shopping the show to producers. No one was interested. Then one of the producers who’d passed on Pippin came back to Stephen with an alternative proposition — the idea of adding music to a small play at the Café La Mama called Godspell. He asked Stephen to do the job in 1971.

“They called me and said, ‘Would you look at this show? We want to move it Off-Broadway, but we think it needs a score.’ The show had some songs that had been interpolated, existing songs by pop writers, and the cast had set some of the hymns to music. ‘By My Side’ was in the show when I first saw it but the producers basically wanted a new score, and the reason the credits say ‘new lyrics’ is because many of the lyrics are from the Episcopal Hymnal. I think there are 13 songs in it, five of which I wrote lyrics for; the rest are basically settings, like “Day By Day,” “All Good Gifts,” “Bless The Lord,” “Save The People,” “We Beseech Thee.”

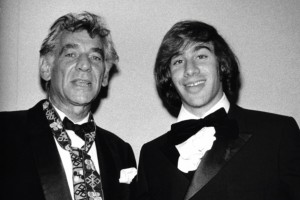

Stephen acquired an agent, Shirley Bernstein, who was the older sister of Leonard Bernstein. When Lenny wanted a lyricist for his Mass, Shirley brought the two men together. Stephen and Lenny became personal friends, closing the circle that began when Schwartz heard Candide on WQXR as a schoolboy. “He had a commission to do a piece for the opening of the Kennedy Center in September of 1971, and it was May, and he was getting increasingly desperate. It was a mammoth, major, gigantic piece and Lenny had nothing done. There were all these little shreds and starts of pieces, and two lines here, and a bit of a tune there, and three months to go to do a piece with 200 singers and dancers. Needless to say, Lenny was relatively panicky at that point. I wrote lyrics to music that he had, and reworked lyrics that he had written.”

Some of the words haven’t aged well — phrases like “I’m so freaky-minded” — while others are clever, like “They can fashion a rebuttal that’s as subtle as a sword / But they’re never gonna scuttle the Word of the Lord.”

“Lenny told me what he was trying to do, and played some fragments. I sort of devised a structure, and he liked it. I had no technique, I didn’t really know how to write lyrics to someone else’s music and I made a lot of mistakes. But there’s much in the piece that I’m proud of, and I think the structure is pretty successful.”

Below, Bernstein & the 23-year-old Schwartz.

Schwartz tells a great story about Bernstein. They went on a vacation trip to Disney World “and Lenny wore sunglasses and wrapped a scarf around his head so no one would notice him, but after awhile he was looking left and right and even behind us. He was getting upset that no one recognized him! When people didn’t make a fuss about him, he got upset. So he began wearing ostentatious clothing to attract attention again.”

Schwartz also tells a sadder story. “I remember one day when I was waiting for him and I was working on a song I was writing for Pippin. He listened for a bit and said, ‘I remember when I used to just sit down at the piano and knock out a tune. Now it’s so hard for me to put two notes together, because I think, ‘Is that worthy of Leonard Bernstein?'”

I wondered how a Jewish man like Schwartz felt about writing two pieces involving Christianity. He revealed that he never had a Bar Mitzvah but always was interested in why we’re on earth and what our responsibilities are, and these questions led him to a closer examination of the bible.

The successes of Godspell and Mass led to the Broadway production of Pippin in 1972, directed by Bob Fosse. “I found success to be very difficult,” Schwartz says. “Fame plays with your head. It distorts your perspective and point of view if you’re that young, and everyone’s carrying on about you. At the same time, I think there was an enormous amount of hostility toward me in the theater community for being successful that early, perhaps for things they didn’t think merited it.

“I was catapulted into fame and prominence before I was ready emotionally at all. You know, I was just this kid who came into New York with illusions about what it would be like to work on Broadway, who thinks it’s all going to be this glamorous, collegial, wonderful atmosphere.”

He wrote a song that expresses his feelings:

“I rose to my present position /

And I gained some celebrity /

Now I bask in their praise and conditional love /

But who do they see? /

The face of a stranger who can’t even say who he is anymore…”

“Ultimately, it was so disillusioning to me, and so unpleasant and painful that I just gave up. I burned out and stopped working. I hid out. I played a lot of tennis, I practiced the piano, took some classes in psychology. Occasionally, fitfully, I decided to chuck writing and show business and go back to school and become a psychotherapist, but ultimately I abandoned that because it’s too much school.”

In his first summer out of college, Stephen directed at a stock theater in New Hampshire and met Carole Prandis, who was playing Gladys Bump in Pal Joey. They married in 1969. Stephen and Carole are still married and they have two children. Their son, Scott, is a theater director, and their daughter, Jessica, works in photographic art. When I asked whether he had wanted his children to go into the arts, Stephen answered: “You wish their passion lay somewhere else. But I believe in follow-your-bliss so I wouldn’t do anything to stop them.”

Schwartz returned to the bible in 1991 with his musical Children of Eden. It is Schwartz’s personal interpretation of Genesis—the story of Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel and Noah. There are several catchy, rousing songs in the tradition of Schwartz’s early musicals, but overall Children of Eden is a serious, thinking-person’s look at family relationships.

“Then Disney called. Howard Ashman had died, and they were looking for someone to work with Alan Menken, whom I knew a little. I had a meeting out there, and they asked me if I would consider doing just lyrics, which I was delighted to do just to get my foot in the door.”

Pocahontas was his first film, in 1995. Then he did The Hunchback of Notre Dame, again with Menken, in 1996. Next he started working on the life of Moses for The Prince of Egypt, the first animated film made by Steven Spielberg and Jeffrey Katzenberg’s DreamWorks. He then embarked on Miracles, a pageant play produced by Rabbi Danny Wise. The book was by Joseph Stein and lyrics by Sheldon Harnick—the same team that created Fiddler on the Roof—while music was written by separate composers for each of three different miracles: Schwartz, Marvin Hamlisch and David Shire.

The main difference Schwartz sees between writing for stage and film is that for theater he needs to write a lot more songs. “A musical will have anywhere from 15 to 42 songs, as in Children of Eden. My animated feature with the most songs was The Hunchback of Notre Dame, with eight. Therefore, there’s a difference in the function of the songs. In films you cannot have a character just stand still and sing. On the other hand, the most effective moment in a Broadway musical is the leading character standing alone on stage, and you hit him or her with three spotlights, and they sing for about five minutes. You cannot do that on film. There, something has to be moving, constantly, visually. You have to do lots of things to compensate for the fact that someone’s just singing, basically, the same emotion over and over again. I have this joke which I’ve often told: If you’re going to write a ballad for an animated feature, the character better be going over a waterfall in a canoe.

“But the similarity is that you are trying to tell a story through the use of song, furthering the plot, illuminating character, revealing emotion. That’s the same whether you’re doing a stage musical, or an animated feature or a television musical.”

The best song in Children of Eden is “The Hardest Party of Love,” a duet between God and Noah which concludes that the hardest part, the rarest part, and the truest part of love is letting go. It is sung by Schwartz himself on a CD called Stephen Schwartz: Reluctant Pilgrim on the Midder Music label. The composer played and sang eleven of his own songs about personal problems and decisions.

“I think careers are such a matter of huge peaks and valleys, and as an artist or writer or craftsman or whatever you want to call it, I think it’s very important to have this middle, straight-ahead path that you’re on. You try to stay in that moderate zone of emotion, not get too high when things go well, not become too devastated when things go badly, just keep plowing ahead. And that’s very easy to say and very hard to do.”

The lyrics of Schwartz’s personal songs sometimes describe sadness and anger. Where does this darkness come from? “Life has brought me some pain and disappointment,” he says. “Friends disappoint you. They break their promises. They let you down. People change.”

One of his Reluctant Pilgrim songs observes a long-time couple: “She doesn’t say: ‘Why don’t you love me like you used to?’ He doesn’t ask: ‘Why can’t you be the one I need?’ He doesn’t say: ‘When did you turn into my jailer?’ She doesn’t ask: ‘When did you turn into a ghost?’…It’s a code of silence…Protect the family secrets…Turn down the bed for one more night of separate dreaming.”

Is this Stephen’s observation of his friends? Does it reflect a period in his own life? The closest Stephen comes to a personal answer is when he writes, in the first person, in the song “So Far”:

“Sometimes I look in your eyes/

I see the pain in the corners/

Little betrayals and lies/

And a part of us dies/…

I see new lines on your face/

Some of them I know I put there.”

At the end of that song, the narrator remains optimistic: “We’re here so far/Still holdin’ tight/…Beat-up but warm, like my old guitar.”

See other Broadway songwriters here.