The most well-known of all piano concertos is fraudulent. It has been for more than a century.

The thundering octave chords that introduce Tchaikovsky’s Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor are so compelling that they were used for the song “Tonight We Love” which was one of the best-selling pop records of the 1940s. Everybody who grew up in that era knew the tune.

In addition, classical pianists from Vladimir Horowitz to Lang Lang pounded out those sonorous chords in concert halls. Van Cliburn’s recording of the concerto, made after his victory at the first International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow at the height of the Cold War, became the first classical album to go triple platinum, and the first LP that many classical music lovers owned.

For many, the concerto is the sound of classical music.

The introduction of the concerto was played at the closing ceremony of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia. The opening bars were played in a Monty Python’s Flying Circus sketch in which a pianist struggled, like Harry Houdini, to escape from a locked bag. And a disco rendition of the concerto was used to open the finale of The David Letterman Show.

Trouble is, those chords were not written by Tchaikovsky. And they were not played when Tchaikovsky conducted his concerto in New York and Philadelphia in 1891 during his only visit to America, and in Russian concerts shortly before his death.

What the composer conducted was distinctly different music. After Tchaikovsky’s death in 1893, a new published edition contained unauthorized alterations and it was accepted by classical pianists from then on. It substituted solid chords (that is, three notes played simultaneously) instead of the rolling arpeggios in the original. The opening that Tchaikovsky wrote was more lyrical, less bombastic. This hummable, most-familiar part of the piece, has a gentle Schumannesque character in Tchaikovsky’s original concept rather than the more-emphatic version that the public knows.

Pianist Kirill Gerstein described the changes this way: “The piano virtuoso Alexander Siloti stepped in. He was one of Tchaikovsky’s students and was uncle to Rachmaninov. As a performer, he saw a way of making it more flashy, more superficially brilliant, louder, more pompous, and, in his eyes, more ‘effective,’ and he had a connection with a publisher. The famous opening chords – which are often played like bombs going off at the start of a war between soloist and orchestra – are not fortissimo, giving it a more lyrical quality and allowing the orchestra to play their important melody more flexibly – and they are actually marked mezzo forte.” (That is, medium loud.)

Through the years, musicians did note that the introduction’s theme seemed to be separate, and independent, from the rest of the concerto. Russian music historian Francis Maes wrote that “for a long time, the introduction posed an enigma to analysts and critics alike.”

The bogus version also changed a middle section from an Allegro vivace assai (meaning “at a lively walking pace”) into a fast, racing prestissimo. Then, in the last movement, sections were cut that introduced harmonically and contrapuntally adventurous combinations of sounds. The posthumous edition eliminated this.

The final minute of the piece was originally lyrical, and was altered to become a triumphal proclamation played fortissimo by the orchestra and piano together. The final cadenza in the posthumous version has a pompous fermata, or hold, before the final restatement of the melody. What Tchaikovsky actually wrote was a slow trill that flows into the final statement of the melody.

Gerstein explained, “I have felt in the past that the third movement was rather truncated and it turns out I was right. There’s the folkloric opening, the lyrical melody, and then a new idea is launched which the familiar version hardly explores. The 1879 edition has 30 seconds more development at this point, which restores a structural balance to the movement, and, I think, a psychological balance to the whole concerto.”

These are not just scholarly fine points; they are substantial changes in key parts of the concerto, altering its entire character.

Tchaikovsky was firm about his wishes. In a letter to his patron Nadezhda von Meck he wrote that the pianist Nikolai Rubinstein asked him to re-work certain passages but “I shall not alter a single note. I shall publish the work exactly as it is! This I did.” He went on to assert, “I am no longer a boy trying his hand at composition, and I no longer need lessons from anyone.”

Thus it was a desecration for anyone to change what the composer wrote. Yet that’s what the musical world has done since the composer’s unexpected death at the age of 53.

Cholera was the official cause, but historians are convinced that Tchaikovsky committed suicide or was ordered to kill himself. A 1993 BBC documentary presented evidence that Tchaikovsky died of arsenic poisoning. Either way, the event was precipitated by the exposure that he was a homosexual who had a close relationship with members of the czar’s family.

For the 140th anniversary of the concerto’s premiere, the State Institute of Art Studies at the Tchaikovsky Museum and Archive in Klin, Russia, published a new scholarly edition of the concerto based on the composer’s own conducting score from his last public concert, with handwritten performance markings.

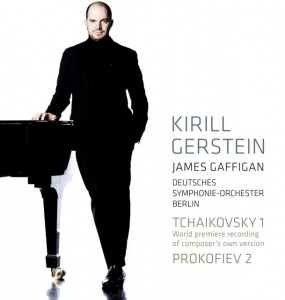

Gerstein’s world première recording of the concerto, on the Myrios label, enables us to hear for the first time the authentic version. It has been nominated by BBC Music Magazine as Best Concerto Recording of 2016.

Gerstein discussed this with me, and with Yannick Nézet-Séguin when they performed together in 2016. Gerstein also wrote in his liner notes, “I find the editorial changes add a superficial brilliance to the piece, while at the same time detracting from its genuine musical character. His own version shows a strong lyrical and noble vein that the better-known posthumous version negates.”

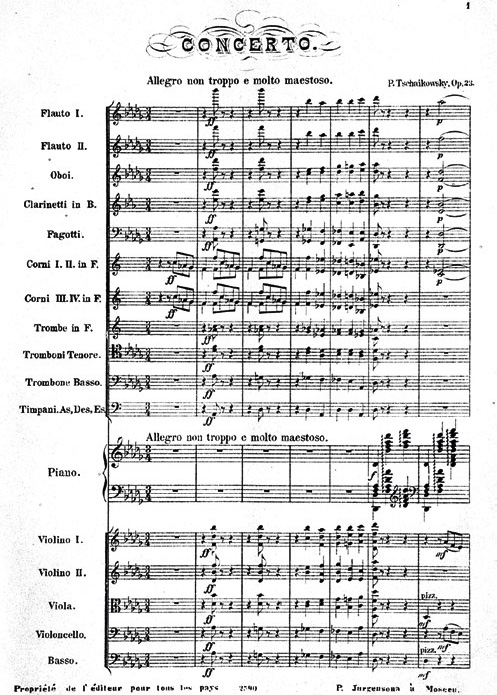

Any notion that Tchaikovsky might have authorized the posthumous version is contradicted by the fact that we now can see the score that he conducted right before his death. [See image] His softer version is heard on this new recording.

Gerstein’s performance makes an overwhelmingly convincing case for returning to the author’s text. At the most recent Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow pianists still performed the now-discredited version. Perhaps someone ought to send Gerstein’s recording to Russia, with love.

Please share your thoughts with us. Address to editor@theculturalcritic.com

Read other reviews on The Cultural Critic