What were the television heroes of your childhood like in real life? And what ever became of them?

Those are the questions that were explored in the play, Music From a Sparkling Planet, in 2001. Frustrated by problems in their personal and professional lives, the characters decide to search for Tamara Tomorrow, the host of an afternoon kids’ TV show of their youth.

Douglas Carter Beane, the well-known Hollywood and Broadway writer, created the script. He grew up in Reading, a half hour outside Philadelphia, and based the play on the Philly TV shows he enjoyed when he was a kid. Beane was obsessed with the afternoon TV hosts of his youth. He never met any of the performers and Tamara is fictional, but Beane used WFIL-TV, Channel 6, as his setting and put real TV personalities in the script, such as Pixanne, Sally Starr and Captain Noah.

Taking my cue from the playwright, I decided to search for the Philadelphia prototypes to see how accurately the play captured their lives. I didn’t have to search far for the youngest of them, because she and I were neighbors and classmates.

Pixanne was a star on Philadelphia’s WCAU-TV starting in 1960, then in New York and national syndication. She was Jane Lazarus, a child prodigy pianist who grew up in the Oak Lane section of Philly and attended Ellwood Elementary School with me. Being practical about a career, Jane took Elementary Ed at Temple University and became a teacher at Shoemaker Elementary in Elkins Park, PA. The parents praised her when she wrote and taught songs to the children, and that gave her an idea for a second profession.

In 1960 she walked into WCAU and told its manager that she’d like to do a children’s program for them: “Just like that, and in a month I was on the air.”

“I loved Broadway shows and always wanted to play Peter Pan,” she continued, “so I designed a version of Peter’s costume for myself, and I looked like a pixie.” Jane used her then-husband’s middle name and became Jane Norman, who played a character she called Pixanne. Not only did Norman have a successful run on TV, she also wrote a best-selling book, “The Private Life of the American Teenager,” and marketed a line of children’s toys, including “Tickety Ted Time for Bed.”

Pixanne was “every 8 year old boy’s heartthrob,” according to one fan, who also described how she “dressed in a very short pixie costume.” Pixanne herself reports about some older fans: “I used to get mail from a bar in Upper Darby — a working-class suburb. The men sent me comments every day, telling me what they thought about my hair and my tights.”

Jane in her sixties was still only 105 pounds and proud that she could fit into her size 6 outfit. But she gave up personal appearances as Pixanne in 2000 to start a singing career as herself. She recorded a CD called “Madly in Love” and made a cabaret appearance at Philadelphia’s Bellevue Hotel.

*

The day I reached Sally Starr on the phone, she was getting ready to make a personal appearance at a Saturday afternoon country carnival in Mechanicsburg, in central Pennsylvania.

She was born Sally Beller in 1924 in Kansas City. “Yes, I’m a strong old bird and proud of it,” she said in 2002; “I have no intentions of hanging up my boots any time soon.” Sally was a country singer who married Jesse “Ranger Joe” Rogers, a personality in the 1940s, and followed him to Philadelphia. “We did a show called ‘Hayloft Hoedown’ from the old Town Hall at Broad and Race Streets and we had people lining up from here to Timbuktu to see us.” Sally also was a disc jockey on religious station WJMJ — it stood for Jesus, Mary & Joseph — until the day in 1951 when WFIL television exec Jack Steck needed a host for re-runs of Gene Autry and Cisco Kid movies. “Steck called me on a Friday and asked me to put on my Western clothes and come to the station. Next Monday I was on the air. It was TV’s infancy, and we had no writers. I ad-libbed everything I said.”

In Beane’s play, a fictitious WFIL producer spots Tamara doing children’s theater and hires her to introduce films in the afternoon. Coming from a theater background, Tamara asks the director what her motivation is for crossing from one camera to another. “Motivation?” he says to her, “If you don’t move there, no one will see you. Is that enough motivation?” Introducing sci-fi movies, she makes predictions of what the future will hold. The playwright explores the differences between what Tamara predicts and what actually happens to her and to her viewers. Tamara’s future, in the play, is a doomed romance with the married producer of her program, and a drinking problem which gets her fired. I tried to see how closely the script mirrors the truth.

Starr’s director and producer, Lew Klein, confronted the rumors that Sally drank. “She was so unrehearsed and off-the-wall. She’d talk to the crew on the air, and it gave some people the impression that she was drunk. But I worked with her for years and I honestly don’t think she ever had that problem. She had others. She had failed relationships and financial problems because men took her money.”

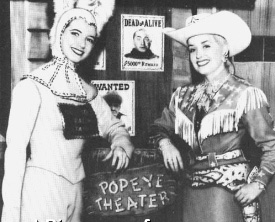

Sally is on the right:

Sally had no affair with her producer, but she admitted to me that she had adventures with some famous performers. A former co-worker says that she also had relationships with younger men. A viewer wrote to a website called Philadelphia Kid Shows and passed along a rumor that Sally Starr had been “a burlesque dancer in her prime and then moved into the kiddie show TV market.” While that is not true, one of her cameramen says that Sally, with her blonde hair and big bust, had some of the aura of Marilyn Monroe. “She was a lot of fun and she packed a pair of 44’s, if you know what I mean.”

Starr was a generous person, frequently treating her crew to dinner or to a night club. After her program was cancelled in 1975, Starr had health and financial problems, but Sally did not become a recluse. She lived in Atco, New Jersey, appeared as Annie Oakley in Annie Get Your Gun at the Three Little Bakers Dinner Theater and hosted a radio program on a Vineland station. She loved making public appearances and thrived on attention. “Thanks for being so nice to me,” she said at the end of our conversation.

*

Gene London was a kids’ host who wound up actually participating in New York theater. He made that direct connection when Tommy Tune hired him to design costumes for Cloud Nine, which had a short run in 1981. London grew up in Cleveland, then Miami Beach, as Eugene Yulish, going to movie matinees with his mother and watching the glamorous stars of the 1930s and early 40s. “That’s how I learned about life. Cary Grant taught me how to dress. But most of all I adored the women, like Joan Crawford and Bette Davis, and I fell in love with their dresses.” Tall, good-looking and with talents for drawing and puppeteering, London found work on TV in New York in the 1950s.

He played and did the voices for two puppets on a DuMont network program called “Johnny Jupiter” that resembled the fictional Tamara Tomorrow, as London talked to the audience from other planets. After two years there, he moved to the struggling young ABC network and took over “Tinker’s Workshop,” which was created by Bob Keeshan just before he went over to the more-prosperous CBS to become Captain Kangaroo. Then London came to Philadelphia in 1959 to do “Cartoon Corners General Store,” a fictitious place where Gene worked for a Mr. Quigley. London would describe visits to Quigley Mansion, draw pictures, tell stories and do puppets. “I wrote and directed it myself, and I started at a salary of only $75 a week. I was always scared to death, but I knew how to tell stories. That was magic for me, and I changed my voice and played all the characters. I also tried to make the show look different. Most TV programs were over-lit. I fought to have shadows that I could move into and out of, like the movies.”

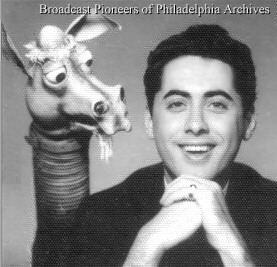

Photo of London, courtesy of Broadcast Pioneers of Philadelphia.

London started on WCAU, channel 10, on Saturday mornings in 1959 and became so popular that the station increased his time to seven days a week. He prided himself on personally answering all fan mail. “I’d send a drawing with every letter, a line drawing that the kid could fill in with color.” Joan Crawford wrote him a fan letter, they became friends and she gave him some of her old costumes. Collecting stars’ dresses then became his hobby. When his show went off the air in 1977 he opened a store that sells theatrical costumes, The Fan Club, on 19th Street off Fifth Avenue in New York City. In June 2002, at age 71, he opened a theatrical museum, free to the public, at the Show Boat casino in Atlantic City.

*

Captain Noah was in his studio in the woods the day I reached him. He went there to write and to paint. “I wrote a children’s book called “Television: What’s Behind What You See” and I’m working on another book with my own illustrations.” The woods are on part of the two-acre property that the captain owns in Gladwyne, on Philadelphia’s cushy Main Line. Clearly, he hadn’t had Sally Starr’s financial problems.

His real name was Carter Merbreier. Born in 1927, he earned a masters degree in theology from Temple University. He was pastor of a Lutheran church when he got the idea for a TV show based on Noah’s ark, which he premiered on WFIL-TV in 1967 under the supervision of Lew Klein. “We were non-commercial, public service, and I received no income from the program. I paid the costs out of my own pocket. My wife and I cut our set out of cardboard in our basement. I paid a puppeteer $100 a week for 13 weeks and couldn’t afford it any longer, so then my wife learned how to do puppets.”

Until 1970 the Captain juggled two careers, at WFIL and at Messiah Lutheran Church, “but there were some parishioners who felt you should serve either God or Mammon, and I should make up my mind and resign from one of my jobs.” In 1970 WFIL expanded his show to 90 minutes every weekday morning and acquired commercial sponsors, and Merbreier gave up his pulpit.

He had some exciting moments on live TV. “Thank goodness for the cartoons we ran,” said the Captain. “They gave me a chance to cut away when something went wrong in the studio. Once, when the female snake handler was bitten and bleeding, we went to cartoon. When the metal-sculptor’s tank nozzles caught fire, and we were about to be blown onto the street, we went to cartoon.”

A woman who identifies herself as Emily M writes that her friends where she lives now, in the South, “claimed I was making up all the songs and crazy little quips of advice that dear old Captain Noah imparted, such as ‘Remember what Captain Noah says — never roam alone.’ That is just one of many. I remember drawing tons of pictures thinking they would end up `posted high in the TV sky,’ as the Captain used to say. Boy, what silly memories.”

In contrast to Starr, when Noah went off the air in 1995 he put his costumes away. “I don’t make personal appearances,” he said. “There’s nothing as pathetic as a has-been in a costume waving at people in a parade.”

*

Before Pixanne’s debut, even before Gene London’s or Sally Starr’s, Chief Halftown was a local daytime celebrity. “I am a real Indian, a full-blooded Seneca, and I told stories, sang songs and introduced puppets,” said Traynor Halftown, 84 years old in 2002. He was a big band singer before World War II, in Buffalo, NY, and had a radio program called “The Seneca Sings.” He said the idea was “an Indian singing like Perry Como — that was the twist.” Didn’t he feel exploited? “Only a white guy would ask me that,” he responded. “No, I wasn’t exploited. I’m proud to be identified as an Indian.”

After serving in World War II, Halftown found that the music business had changed and there were no jobs for band singers. Then a small Philadelphia AM station, WDAS, was successful when it put Eagles halfback Bosh Pritchard on the air as an untraditional deejay. WDAS was pioneering a trend away from deejays who were music experts to deejays who discussed other subjects and expressed their personalities. “They wanted me as a similar gimmick,” said Halftown, “a singing deejay using the Indian shtick.” His radio gig led to him being asked to go onto TV. From 1950 til 1999 “Chief Halftown and Friends” was on Channel 6. Later, he worked weekends doing a live Indian show at Dutch Wonderland on Route 30 near Lancaster, PA. “Through the years I did research on Indian culture. It’s been good for me and good for my show,” he added.

*

Some of the kids’ hosts weren’t quite what they seemed. The most outrageous example is Rex Morgan. He was a partner of Happy the Clown on the TV show of that name, sometimes subbed for Sally Starr, and also was the host of “Morgan in the Morning,” where he showed old movies. Morgan had been an army colonel and mortician in the Second World War. He performed the autopsy on Field Marshall Goering and personally embalmed General Patton, or so he said. On TV he was all fun, but the WFIL crew saw a darker side. They say he carried a hangman’s noose in his car and often showed off a guidebook with photos of dead bodies and details on how to kill people.

Happy the Clown, a former radio announcer named Howard Jones, didn’t show much affection for kids, and neither did his assistant. One old viewer shares a memory of the day his parents took him to be in the audience for the show: Happy was off that day and the assistant, Sawdust Sam, was filling in. “One of things on the show was to get marching sticks that you got to keep. Everybody paraded around tapping their sticks together to the music, and at the end you climbed up a ladder and slid down a sliding board. When it was my turn, old Sam stopped me and said ‘you’re too fat, little boy’ and would not let me climb the ladder, which of course sent me running off the stage in tears straight to my parents. This was live TV. I told my Dad, and I thought he was going to get up and punch old Sam.”

Beane wrote about Philadelphia TV because that’s what he grew up with. But, even for a writer from a distant city, Philadelphia would be an interesting locale. It was a unique television place, America’s third largest city at that time, but with much more of a small-town atmosphere than New York or Chicago. Philly TV personalities loved to make personal appearances in neighborhoods and at shopping centers, and built personal relationships with their viewers. More kids and teenage programs seemed to originate from Philly than from any other city, including Paul Whiteman’s “TV Teen Club,” which WFIL fed to the ABC-TV network in its early days, and, later, “Bandstand.”

That Channel 6 presented most of these programs was not just happenstance. The station was affiliated with ABC which, in those days, was barely solvent. In the 1950s, it didn’t even send a feed to its stations during the afternoon. Because ABC didn’t offer daytime programming, local stations had to develop their own things. Station Manager Roger Clipp used to tell his staff: “Create programs for the kids. If we get `em young, they’ll watch us as they get older.”

Or even, as it turns out, write plays about them.