This article, prompted by the world premiere of two operas, was originally published in The Opera Critic, the international journal for opera professionals and aficionados.

The Creative Process

Two high-profile opera premieres took place within two months — and both of them were created by one librettist, though with different composers. That’s a most unusual occurrence.

Kevin Puts composed the music for Elizabeth Cree, a thriller about grisly serial murders in London in 1880, overlaid with the trial of Mrs. Cree for allegedly poisoning her husband. Mason Bates composed an opera about the life and inventions of Steve Jobs. Both were set to words by Mark Campbell.

Having just attended The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs in Santa Fe and rehearsals of Elizabeth Cree in Philadelphia, I’m impressed by the theatricality of both. The Jobs opera is a crowd-pleasing sensation, and Elizabeth Cree appears headed for a comparable success. Both of them achieve the goal of exciting audiences.

It’s been informative to see the composers and the librettist at work, and to learn about their personal inter-relationships.

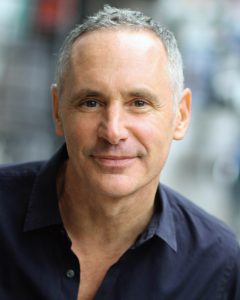

Silent Night, the first opera by Puts and Campbell (pictured here), won the 2012 Pulitzer Prize for Music. Commissioned by Minnesota Opera and the Opera Company of Philadelphia, it told the true story of a truce during World War I when English, German, French and Scottish soldiers put down their arms in observance of Christmas. Campbell said that the message of the opera is “War is not sustainable when you come to know your enemy as a person.”

The pair followed up with another Minnesota production in 2015, the Cold War spy thriller The Manchurian Candidate. The story is a metaphor for the plight of battle-scarred returning vets and a central character is the mother of one soldier, a right-wing fanatic who is bent on a “holy crusade” to restore the country “to its original purity.” Elizabeth Cree, therefore, is the third joint composition by Campbell and Puts. So, then, are they a team? Are they partners?

Well, not in their personal lives. Puts is married to New York Philharmonic violinist Lisa GiHae Kim, while Campbell’s husband, Steve Tracy, co-founded a Brooklyn-based manufacturer of scented candles named Keap.

How does Puts (pictured on the left) handle the fact that Campbell continues to work with varied composers? Does he feel that Campbell is “cheating” on him?

How does Puts (pictured on the left) handle the fact that Campbell continues to work with varied composers? Does he feel that Campbell is “cheating” on him?

Not at all. Puts says that Campbell is the perfect collaborator. “But it takes me two or three years to write an opera score while Mark can write a libretto in a few weeks. I don’t want to stand in the way of his creativity.” Campbell adds that he needs to keep writing “to put food on the table.” He was not able to give up his day job as an advertising copy writer until after he received that Pulitzer.

Campbell has written lyrics for Broadway shows and more than fifteen opera librettos, with varied subjects and tone. Puts was born in St. Louis in 1972, grew up in Michigan, and earned degrees from Eastman School of Music and Yale University. Puts’s instrumental compositions have been praised as richly colored and melodic, “emotional, compelling, and relevant.”

Puts has written progressive harmonies and created dissonant timbres, but he is unafraid of writing old-fashioned melodies. Campbell comments, “Composers are often blamed for tunelessness in modern opera. I think it’s the librettists’ fault as well, because we often don’t give the composers organized songs for them to create tunes with. If a lyric wanders, then the music wanders, too.”

Musicians have compared Puts’s style to Copland, Barber, Britten and Bernstein. He talks more about Mozart. It’s significant that Campbell holds Mozart up as a paradigm because Mozart, in fact, is one of the rare composers who succeeded with both orchestral and theatrical compositions. Think about all those skilled creators of orchestral music (Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Mahler) who failed to create a body of opera hits. And those masters of opera (Rossini, Verdi, Wagner, Puccini) who had no fame with non-theatrical compositions.

The demands of the two disciplines seem to be at odds. Yet composers Puts and Bates seem, so far, to be encompassing both. Librettist Campbell explains that he gravitated towards serious theater and grand opera because of the heightened emotions: “We go to Sweeney Todd because we could never commit that kind of revenge in our own lives, and we can never fall in love as intensely as Tosca does.”

Puts says, “I think that if composers think at all about their audiences — and of course no composers talk about their audiences, because they think they’re not allowed to think about their audiences — but if they do at all, what could we use right now? I suppose we could use comfort. We could use a musical balm. That’s a place I can go.”

The head of the Minnesota Opera teamed up the two men to work on Silent Night. Puts said that “I found I love to have a program in mind a lot more than having a completely blank canvas. I respond much better if there is a story to be told.” Campbell writes an entire libretto and only then does Puts write his music. He doesn’t even need to read the original novel or see the movie that Campbell used for his source.

I understand his logic. When I read the Peter Ackroyd novel about Elizabeth Cree I was fascinated by characters and literary references that Campbell omitted from the opera in order to improve clarity. I loved Ackroyd’s digressions, but remembering them only cluttered my attention as I viewed the opera. I recommend that opera-goers not read the novel first. It will make great supplemental reading afterwards.

Puts describes his process of composing an opera: “I read the libretto and react to it. A sound will come to me — the harmonic and melodic structure and the pace.”

Campbell created three other operas in 2017 in addition to the Cree and Jobs projects: Dinner at Eight for Minnesota Opera with composer William Bolcom, Some Light Emerges for Houston Grand Opera with composer Laura Kaminsky and co-librettist Kimberly Reed, and The Nefarious, Immoral but Highly Profitable Enterprise of Mr. Burke & Mr. Hare for Boston Lyric Opera with composer Julian Grant.

Even though he has many years of experience, Campbell still is apprehensive as the opening nights for his operas approach. “People think I’m calm, but I’m a nervous wreck. I put on a brave front but deep inside I’m a terrified child.” As he sits next to me at a rehearsal, Campbell writes notes. To the stage director, “Aveline needs a cape or a hat in this scene, to indicate that she’s leaving the building, not just walking out of the room.” To the supertitle person, “Delay projecting this title until the last word, so it won’t give away the joke.” He needs to concern himself with every detail.

Everything has a main objective — to make the story clearer. Puts, like Campbell, feels that the rehearsal process is draining: “Premieres take it all out of me!” He finalizes the piano score early so the singers have something to learn from and rehearse with, and then he spends a good half a year doing nothing but orchestrating this. “It is a great joy to finally realize my ideas orchestrally, since they have been in my head all along, but it also is extremely time consuming. I am not one who thinks of orchestration as a dressing up of the piece, but as a series of important decisions that the emotional impact of the piece hinges on. Is this line best with solo oboe, or does the harp double on some of those notes?

“I produce a 400-page score which my publisher edits over the course of a month or so. I get together a group of 16 musicians and we play through it. I adjust the score according to what I like and don’t like, trying to imagine the orchestra coming from a pit rather than the stage we used for the read-through. We do another round of editing and then we finally make the separate orchestra parts for the musicians and deliver this set to the company.

“About four weeks before the premiere, the cast, the covers, the director, the librettist, the rehearsal pianists all arrive and begin to rehearse from the piano score. A couple of days of music rehearsals, with no attempts to stage anything, and then the process of staging begins. The reality of getting cast members onto the stage and off, with enough time to change costume for their next scene (many of the cast are doing two or more roles), often means adding music. The librettist or the director may decide, even at this late hour, that for the sake of clarity a line or more of text needs to be added. This is easy enough to do in a play, but in a piece of music that relies on the technology of notation and printed parts which were printed long ago and now in the hands of the performers who will play the work, this an often stressful and difficult task. And it may happen 30 or so times, right up until we rehearse with the orchestra, which is about a week before the premiere. So I am going to rehearsal in the morning and spending the rest of the day making adjustments to the score.

“But these issues are minor compared with the stress of hearing the work for the first time, with orchestra and singers, five days before the piece will open. I think of myself as someone who, with experience, has learned to translate what I hear in my head to information that singers and instrumentalists can read on the page and make sense of with minimal questions asked. But I am not infallible. I have never before written a 16-piece orchestra piece and when I finally hear it, I am shocked in places to find I slightly miscalculated the orchestration or the balance between singers and orchestra. So this requires another set of adjustments at a desperately late hour, frantically reworking part of the score and sending out lists of changes.

“Then we finally get into the hall and hearing the orchestra in the pit requires more adjustments. I work with the conductor (the wonderful Corrado Rovaris, in this case) to compromise on his feelings about tempo and expression and mine. I rely on him to keep everyone together, to keep the singers, who are not just parked somewhere and belting out lines, but who are moving about the stage dynamically while the orchestral musicians cannot see them at all. I don’t even have a moment to think, ‘What will the audience think of this story, this music?’ Frankly, there isn’t time. All my energy is consumed by helping others realize my musical vision for the piece, which began two years prior.

“And then, yes, there is the reality that others who are not even remotely invested in my weeks and hours of work, sweat and tears for two years will suddenly descend on the work and pass judgment in a heartbeat. It happens, but what is most important is that I am satisfied with what I am hearing, that it is as I imagined it. That is all I can hope for and it is by no means easy to achieve.”

Puts has a similar aim as Campbell’s as he listens to the music: to lighten the orchestration to make the text clearer. “I ask myself, ‘How can I make my music more clear and fresh. I want to communicate. I want audiences to be held in the moment, and be taken to the next moment. If that’s not happening, I feel like I’m falling short. I am always looking for ways to create that kind of spirit and beauty, that balance and perfection and leanness of sound.”

Mezzo Daniela Mack is a revelation in the title role. Campbell, Puts, Mack and tenor Joseph Gaines previewed some of the Cree music at a concert last Spring in the crypt beneath Manhattan’s Church of the Intercession, where Alexander Hamilton is interred. The Crypt Sessions are the invention of Unison Media’s Andrew Ousley, who chose this ghostly church in the neighborhood made famous by Lin Manuel Miranda’s In the Heights. Puts was at the piano but he complained that he was rusty: “I’m not really a performer.”

The composer of The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, on the other hand, is a virtuoso performer. Forty-year-old Mason Bates is a trained classical musician who also has worked as a disc-jockey, spinning records at clubs. He is an experienced composer for orchestra who just wrote his first opera. During his symphonic works and his new opera he sits amid the orchestra musicians as he manipulates his electronic gadgets.

The Chicago Symphony commissioned the premiere of Bates’s Alternative Energy, which was conducted by Riccardo Muti, and later by Yannick Nézet-Séguin in Philadelphia. Bates portrayed the uses of energy in 20th and 21st century America, and his imagination of how it will develop in 22d century China and 23rd century Iceland. He used a sonic palette that included percussion, mechanistic sound effects and amplified recordings of power plants and bird songs.

Bates, with his involvement in the computer world, came up with the idea of an opera about Steve Jobs. He sought out Campbell to be his creative partner, and Campbell chose to present a seemingly-random group of episodic anecdotes to build a narrative about a self-centered, obsessive, demanding man who gains self-awareness when he learns that he is dying.

The two composers, Puts and Bates, know each other and have respect for their disparate work. Bates’s music integrates electronica and various sound effects with a full orchestra, including lovely soft moments as well as full-throated climaxes. Among these three creative men, Bates seemed to be the calmest, as he treated his wife to vacation pleasures such as fine restaurants and a day at a spa. He took advantage of the fact that they were in one of America’s most desirable destinations, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Elizabeth Cree has its world premiere Thursday, September 14, 2017 at the Perelman Theater of the Kimmel Center in Philadelphia as part of Opera Philadelphia’s Festival O17. After five performances there, the production will travel to the Chicago Opera Theater in February 2018.

The Review

The British statesman Winston Churchill coined the expression, “It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” He was speaking of the Soviet Union. The quotation, however, also could be applied to Elizabeth Cree, the murder-mystery opera which had its world premiere, launching Opera Philadelphia’s O17 Festival of five productions within a ten-day period.

This is the fictional story of a woman who is on trial for poisoning her husband in 1880, at a time when a serial killer is murdering and dismembering innocent victims in their London neighborhood. Mrs. Cree is an actress and singer, which gives opportunity for catchy music-hall numbers composed by Kevin Puts.

This new opera keeps us guessing about who’s guilty of what, and is full of surprises. We may think we know where it’s heading — or are we intentionally being misled? Elizabeth Cree focuses on with grisly violence, although the bloody slashings are shown behind a scrim, intermingled with the comic relief of the music-hall scenes.

Elizabeth Cree is set in a time of economic inequality and alienation, a disturbing world of dark alleyways and impenetrable fog, populated with historical figures including radical thinker Karl Marx, novelist George Gissing, and popular theater star Dan Leno (a precursor of Charlie Chaplin). All of them gather in the Reading Room of the British Museum where they discuss the urgent necessity for reform, while a police inspector targets these celebrities as possible suspects in the murders.

(Marx famously wrote, “What is one murder here or there compared with the historical process?”)

The talented cast is headed by mezzo Daniela Mack, whose previous work in Handel at Santa Fe barely prepared me for this star turn. She dominates the action with her dramatic intensity and soaring voice. Tenor Joseph Gaines is spectacular as the music-hall comedian, a triple-threat with his acting, dancing and singing. Baritone Troy Cook uses his resonant voice superbly as the husband John Cree. Daniel Belcher, Matt Boehler, Deanna Breiwick, Jason Ferrante, Jonathan McCullough, Maren Montalbano, Melissa Parks, Thomas Shivone and Daniel Taylor complete the versatile cast.

Puts’s orchestral writing supplies colorful mood — and horror — while his vocal writing is melodic. The characters are given grand solo opportunities. When we see a work labeled as a “chamber opera” we imagine delicate orchestration, primarily with soft strings. Puts’s score for 16 players, however, is deliciously variegated. The orchestral sound has rich and colorful texture, with good use of snarling brass. Corrado Rovaris conducted the riveting performance.

David Schweizer (with years of experience for Joseph Papp and Lincoln Center) directs the 28 scenes with fluidity, moving rapidly among courtroom, police station, music hall, the streets of London and the British Museum. Set and costumes were designed by David Zinn, choreography is by Jesse Robb, and the crucial projections are by Alexander V. Nichols.

After the real murderer or murderers are revealed, you may wonder if there’s a reason to see the opera a second or third time. There is. After all, we go back to Rigoletto even when we know who’s in that body bag. Elizabeth Cree is worth repeated viewings for its vivid characters, ingenious development and gripping music.

The Steve Jobs opera is reviewed in this separate article.

Below, Campbell and Bates at the premier of The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs: