Embracing the Contemporary: The Keith L. and Katherine Sachs Collection. Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The most talked-about major shows at the Philadelphia Museum of Art have been Van Gogh, Renoir, and other romantic figures from the 19th century. Therefore, some of the public may be unaware of the museum’s considerable collection of contemporary art.

More than one thousand pieces created since the middle of the 20th century are housed there. Now a bequest from Keith and Katherine Sachs is adding 97 more. Most of them went on exhibition from June to September, 2016.

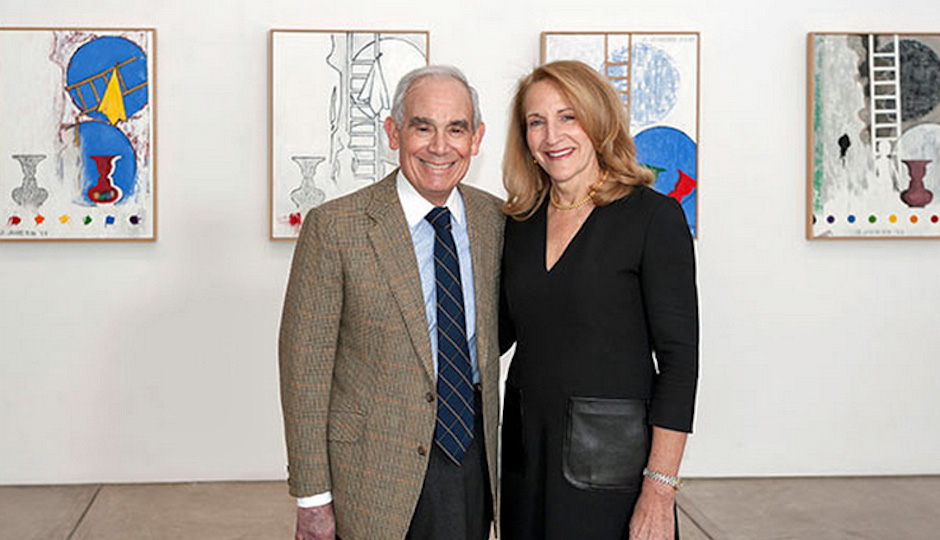

The couple assembled one of the nation’s leading private collections of contemporary art. Until now, the pieces have been on the walls, floors and lawn of their Philadelphia home and New York City apartment. It is, simultaneously, encyclopedic and deeply personal.

Keith and Katherine began collecting art soon after they met as students at the University of Pennsylvania in the 1960s. She was an art history major, he was a business student at Wharton. They started buying objects that appealed to them on a gut level, then became friendly with the artists who created those pieces, asked each of them what they were proudest of, and tried to gather as many of those as possible. About half of the works date from the past fifteen years.

All along, they aimed to establish a collection that never would be fragmented, or sold off piece by piece. They wanted to have a structured, comprehensive grouping of the art of their generation that would be preserved — almost the way a museum would gather such treasures.

Eventually, they decided that the collection should be deeded to an actual museum. Both are Philadelphians and have worked with the Philadelphia Museum of Art for many years, so the choice was a no-brainer.

Katherine Sachs first became involved with this museum when she volunteered to stuff envelopes during the big Van Gogh exhibition of 1970, and she later worked as a museum guide. Keith Sachs is the former CEO of Saxco International, a distributor of packaging material, and board chair at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Design.

What strikes me most is the breadth and the variety of media, forms and subjects. The exhibition includes video art, photographs and sculpture as well as paintings.

While the extensive group of Jasper Johns paintings are impressive, I am more intrigued by some more unusual works. For example: Person Leaning (Persona appoggiata), a six-foot-tall mirror with a painting of a man on its surface, seemingly leaning against its left edge and gazing across the mirror. As we observe him, of course, we are seeing a reflection of our own image, so the man seems to be looking at us. Michelangelo Pistoletto created this in 1964, using painted tissue paper on polished stainless steel.

Each visitor will admire different pieces, but another favorite of mine is Chaise lilas avec oeufs (Lilac Chair with Eggs). The Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers encrusted the seat of a dining room chair with broken eggshells and covered the assemblage with pinkish-white paint. The idea seems to be that we are likely to eat eggs while sitting in a chair; thus the artist created an unexpected image of a common everyday custom.

Fire by Richard Tuttle blurs the line between painting and sculpture. It is a deceptively simple, irregularly-shaped horizontal plywood form placed on the floor without a pedestal, painted with pink acrylic. (The vivid color possibly was to prevent people from accidentally tripping over it.)

Connect is a quintessential emblem of controversial modern art, painted in 2002 by Robert Ryman, a large white-on-white oil on canvas. This is the sort of thing that cynics call a joke but The New Yorker has proclaimed that “no museum collection of painting since the nineteen-sixties can be authoritative without an example of his work.” When you come close and observe it from different angles you see a third dimension as the paint adheres to the canvas in hills and valleys. A photograph can’t show any of this, but the close eye will see varieties of paint, and Ryman’s process in binding them to his surface.

Boy With Frog is an 8-foot-tall sculpture by Charles Ray in Renaissance style of a child holding aloft a frog he apparently has just caught. As a metaphor for the joy of discovery, and a symbol of love for beauty, this is a perfect distillation of the Sachs collection.

The Sachses say that their friendship with the artists opened their eyes to greater appreciation, because the creators talked about what they hoped to, and tried to, achieve. For example, Ray explained the classical historical references in his Boy With Frog. And he tried to show how engaged the boy was with his discovery, by altering the length of his arms. He also wrestled with the question of how high the boy should lift the frog, to best display his wonderment. The artists shared stories about the questions they themselves pondered as they worked.

I asked about Jasper Johns in particular, because he’s the most famous, and the oldest, of their friends. “He’s a soft-spoken Southern gentleman who happens to be the greatest living artist,” says Keith; “He was reticent at first, but became open. He guides us to think more, rather than making definitive statements.”

Johns, age 86, visited the Sachses this summer and toured the exhibition.

Most of what’s here is on loan, pledged as a gift but not to be permanently transferred for many years, I recommend coming to see it now. The art is returning to the Sachs’s homes at the end of the summer.

A shorter version of this story appeared in Broad Street Review.

Read other reviews on The Cultural Critic