A refreshed The Gross Clinic by Thomas Eakins was put on exhibit in 2010 in the same room as Eakins’s The Agnew Clinic, a comparable work of art. These two paintings of similar subjects came together for an extended museum showing for the first time since 1893.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art have performed an important restoration of The Gross Clinic. Now the painting is seen as Eakins envisioned it, revealing details that were distorted since an aggressive cleaning and “improving” took place in the 1920s. “The picture that’s been in a thousand textbooks,” said curator Kathleen A. Foster, “unfortunately is not the one Eakins painted.”

Eakins was a graduate of my high school, the Central High School of Philadelphia, and he attended Jefferson Medical College and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he later was director. So this exhibition is of intense interest for Philadelphians, but its importance extends far beyond the local.

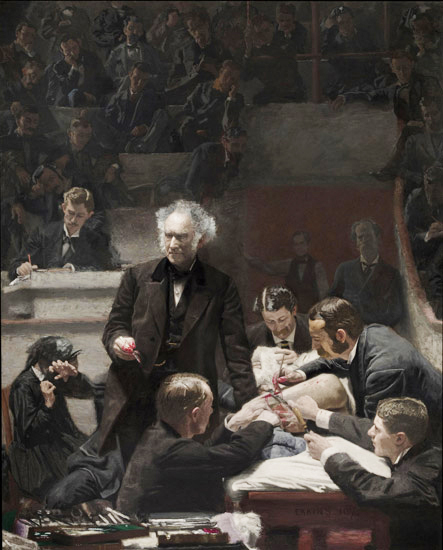

Eakins was a 30-year-old anatomy student and a not-yet-famous painter when he started The Gross Clinic in 1875. Gross (1805-1884) was revered as a teacher and surgeon and the painting’s full title is “Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic).” Eakins’s depiction of a doctor performing surgery for medical students in a hospital amphitheater is now esteemed as a landmark of medical history and a masterpiece of 19th-century painting. But at the start it was condemned for being too realistic.

Eakins hoped to have The Gross Clinic included in the exhibition hall at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, celebrating 100 years of artistic and scientific advancement in the USA. His painting was rejected and was shown, instead, at a U.S. Army medical post nearby. Three years later the painting was exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and then at New York’s National Academy of Design.

Critics wrote that it was horrifying to see blood and knives and a naked thigh. The Art Journal said it was “black and disagreeable. It must be felt as a degradation of art.” The New York Times said: “The pincers and lancets, the spurting blood…are bad. Power it has, but very little art.” The New York Tribune said “It is hard to look at it long…powerful, horrible and yet fascinating” and “one must condemn its admission to a gallery where men and women of weak nerves must be compelled to look at it.” These quotations were posted in the entranceway to the new exhibition.

Much of the 8 foot by 6 foot painting is black and the students are in deep shadow, thus spotlighting the surgeon whose hair gleams with the reflection of sunlight coming from above. But the dark color of the painting, as well as the perceived darkness of its subject, alienated many viewers.

The Jefferson Medical College, which owned the painting, commissioned a cleaning after the artist’s death. Well-meaning craftsmen lightened and brightened The Gross Clinic, thus drawing attention to figures that Eakins intentionally put in shadow, and detracting attention from the surgeon. That restorer removed a final dark layer that Eakins applied specifically to mute parts of the painting, and added a yellowish-orangish tint. Because the painting was at the college, not in a gallery or museum, critics did not report the changes. Eakins widow privately wrote that the cleaning had “destroy[ed] the tones” that her husband created.

This masterpiece stands as an intersection of art and science, of painting and surgery. It captures a time when doctors were all male, where they wore ordinary, unsanitary street clothes and where all illumination came from a skylight above. Surgery in those days was scheduled between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. because that’s when the sun was high.

A fascinating contrast is seen in The Agnew Clinic, created by Eakins 14 years later. That painting chronicles the use of electrical lights, the presence of a female assisting the surgeon, white gowns and sterilized instruments in a covered case. In the intervening years, Joseph Lister’s discoveries had led to antiseptic practices by Dr. D. Hayes Agnew at the hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, and by others. The painting itself is larger (7 feet by 11 feet, horizontal) because Eakins wanted to give more space to the group of students who had commissioned this piece. The most prominent similarity between the two paintings is the focus on a charismatic surgeon who turns from his patient to address his students. Eakins himself appears in both paintings.

The museum displayed these clinic paintings in the same room at right angles to each other. This way you can easily turn your eyes from one to the other. Or step back and seem them together. The curators wisely chose to not have them side by side on one wall where the larger Agnew might have overpowered the Gross. The colors of the walls replicate those of the Centennial Exposition hall, so the work was now in the setting that Eakins dreamed of.

The exhibit included much more—about Eakins career, the art of restoration, the Centennial Exposition and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. After six months in this space, the art went on exhibit in the Academy.

The full painting, with students visible: