Masterworks of French Photography, 1890–1950, at the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, October 2016.

The famous Barnes collection centers on French paintings from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which makes this new exhibition splendidly pertinent. It presents photographs of people and places in France (especially Paris) during that same time period.

Thom Collins, the executive director and president of the Barnes Foundation, has a background in film, and he took the initiative to borrow these photographs from the private collection of the New York physicist Michael Mattis and his wife, Judy Hochberg. They have acquired high-quality vintage prints, developed by the photographers immediately after they made the negatives.

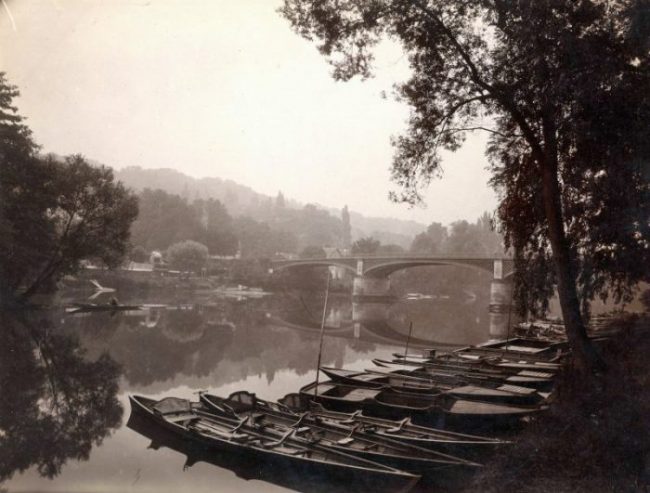

This is the first time the Barnes is showing photographs of some of the same scenes that were observed by its painters. Neighborhoods and subject matter are similar. For instance, when we see Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photograph of Parisians relaxing, Sunday on the Banks of the Marne, we immediately think of Seurat’s painting A Sunday on La Grande Jatte. After viewing the photo, we have an even greater appreciation of what Seurat put on his canvas .

The glory of the exhibition is seeing the relationships between these photographs and the paintings.

The title of the exhibition, “Live and Life Will Give You Pictures,” is a quotation from Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004), a pioneer of candid photography who put aside his heavy studio camera and took a small Leica with him as he prowled the streets. “Photography is not like painting,” Cartier-Bresson said, “You must know with intuition when to click the camera.”

The exhibit covers a period when Parisians were exploring ways to use their free time as new laws required employers to give workers paid vacations. Paris was becoming an industrialized city with broad avenues and boulevards, where people increasingly sought diversion in cafés.

Eugène Atget (1857-1927) tried to document the old Paris. In 1800 it was still a medieval city of 500,000 and by 1870, when Atget was a teenager, its population topped two million. Old buildings were being torn down and Atget went on a mission to preserve images of the past.

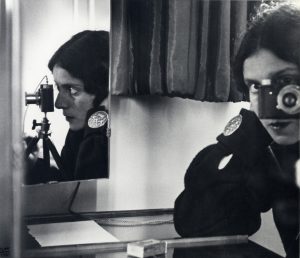

Brassaï (pseudonym of the Hungarian-born Gyula Halász, 1899-1984) wandered the streets at night and took photos in cafés and bars, while Ilse Bing (1899-1998) chronicled dancers at the Moulin Rouge. Bing also performed a service by capturing a glimpse of Paris’s Yiddish theater culture which was soon to be extinguished.

On the right, self-portrait by Bing:

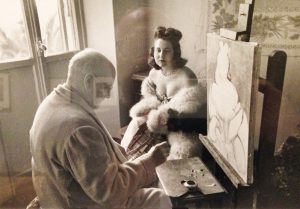

The exhibit includes a celebrity section with images of some of the great painters. Particularly striking is an informal photo of Stéphane Mallarmé and Auguste Renoir taken in 1895 by Edgar Degas. Beyond the artists already mentioned, this exhibit features beautiful pictures taken by Man Ray, Berenice Abbott, Erwin Blumenfeld, Eugène Druet, André Kertész, Francois Kollar, Jacques-Henri Lartigue, Dora Maar, Lisette Model, László Moholy-Nagy and Félix Thiollier.

Below, Matisse and a model, photographed by Degas.

Because Barnes’s will mandates that his paintings remain exactly where he arranged them, in specific rooms that can not be used for any other works of art, it was impossible to display the photographs and the paintings together. This photo exhibition, however, is on the same floor as the gallery with the paintings; it’s only a short stroll from one to the other. I recommend seeing the photos first, and allowing time for a leisurely stroll through Barnes’ permanent collection immediately afterwards.

Please share your thoughts with us. Address to editor@theculturalcritic.com