Picasso: The Great War, Experimentation and Change. Columbus Museum of Art and the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia.

Picasso: The Great War, Experimentation and Change. Scala Arts Publishers.

This exhibit and book explode the conventional notion that Picasso’s career was divided into distinct periods such as blue, pink and cubist. During the stress of the Great War he seemed to abandon cubism, but here we see that he returned to it recurrently.

When World War I broke out, French and British publications denounced cubist art as a product of Germany. They made a case that cubism’s breaking up of objects was analogous to Germany’s fragmenting and dismantling the balance of nations, and precipitating a world war.

As the German army advanced upon Paris, many Frenchmen yearned for the good old days before the invention of cubism, and newspaper cartoons repeatedly attacked that genre. [See an example.]

The French establishment felt that cubism was foreign to their culture. The German dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler was the promoter and salesman of Picasso’s cubist works, causing many French people to associate cubism with the hated Germans. In addition, the French were suspicious of Spain, Picasso’s birthplace, which stayed neutral but whose aristocracy, Catholic Church and the Spanish Army favored the German cause, mostly due to conservatism and admiration of Prussian militarism.

All of this put Picasso’s career in a precarious position.

Because he was a Spanish national, the 33-year-old Picasso was not drafted into the French army. He never directly addressed the war as a subject in his art, but the conflict did influence him tremendously, and caused him to radically change his style.

After seven years concentrating on geometrical cubist forms (following his earlier Rose period and Blue period) Picasso made a shift and started painting naturalistically, almost classically. He allowed people to think that he abandoned cubism. He also found a new dealer, who was French instead of German. But what this exhibit discloses is that Picasso did not renounce that style. Throughout the conflict and into the 1920s he shifted back and forth, alternately creating cubist and natural paintings.

Two contrasting canvases hang next to each other: Harlequin Musician (seen to the right) is severe, almost abstract—a veritable paradigm of cubism. Two feet away is Pierrot, a naturalist painting of a melancholic seated figure with graceful fluted folds of his garment. His hands are holding a mask, which provides a small link to the Harlequin; otherwise the paintings are diametrically opposed.

Pierrot is shown below, both © 2016 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

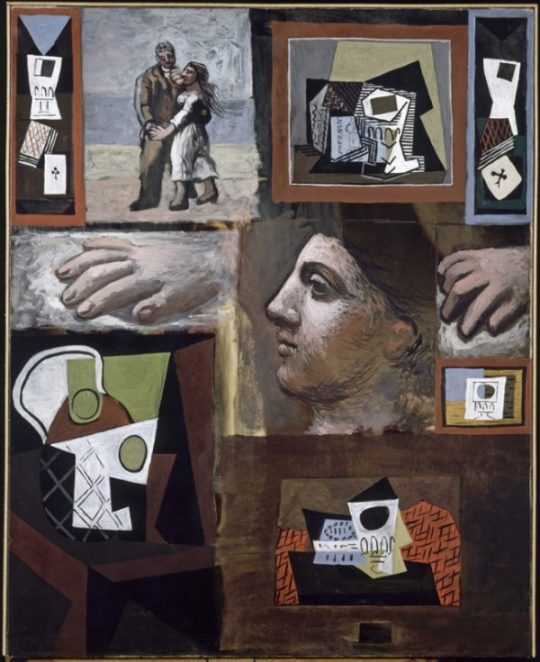

Picasso sometimes combined elements of both forms in one work of art, as in Studies, a 1920 oil [see picture at the top of this story] which is part of this exhibit. We see cubist still-lifes abutting classical figure studies on one canvas.

Observers will detect sharp differences between the two styles, but Picasso said that the two approaches were not necessarily antithetical: “If the subjects I have wanted to express have suggested different ways of expression, I have never hesitated to adopt them.”

Simonetta Fraquelli, curator of this exhibition, says that Picasso did not repudiate cubism but, rather, was making “a passionate declaration of his freedom of expression.”

Objects were loaned to this showing by private owners and museums in Paris, London, New York, Washington, Barcelona, Columbus, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Brooklyn, Houston and San Francisco. At the Barnes, this exhibition is separate from its main collection. That permanent collection contains ten Picassos from the same period which cannot be removed from the spaces that were chosen by Albert Barnes. Patrons should take the opportunity to see them during their visit.

I especially recommend lingering in room 10 before Still Life-Glass and Peach, one of his later cubist paintings, circa 1923.

Towards the end of the war, Picasso designed sets and costumes for the ballet Parade by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russe, presented in Paris with a story by Jean Cocteau, choreography by Léonide Massine, and music by Erik Satie. Picasso’s set caricatured modern life in cubist manner but the curtain he designed was classical. He constructed large paper mache figures for the production that stood in the center of the Barnes show. One of his original costumes also was displayed.

Videos of a production of Parade and a documentary about Picasso during the war were extra features at the exhibit.